THE JOURNAL

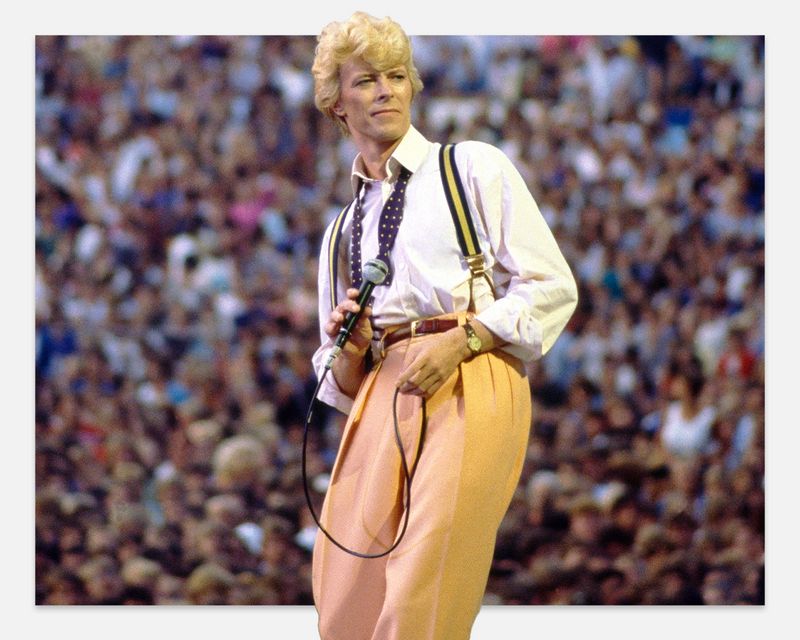

Mr David Bowie on his Serious Moonlight tour in Edmonton, Canada, 1983. Photograph by Mr Denis O’Regan

Mr David Bowie, the late, great artist who would’ve turned 75 today, underwent a marked reinvention in 1983. This was nothing unusual, but the iteration of Bowie who emerged that year was perhaps his most quietly radical. Three years earlier, with the release of his Scary Monsters (And Super Creeps) album, the singer had lurked as the progenitor of the New Romantic scene, smeared in greasepaint and dressed in a wire mesh Pierrot costume by Ms Natasha Korniloff. Then followed a three-year pause as he extricated himself from his contracts with his manager and his record label, RCA.

Bowie’s reappearance, at a press conference at Claridge’s hotel in London hosted by his new label, EMI, was captured by the BBC. “Against serious opposition, and for very serious money, they’ve just signed a real superstar,” intoned the reporter. “No other pop performer, except perhaps Jagger, could… pull off the event with quite such style.”

The Bowie who emerged to the waiting journalists was almost unrecognisable. In a pale grey double-breasted suit with a loosened tie, his teeth whiter and straighter than before and sporting a biscuit-coloured tan and a casual blonde bouffant, he looked healthy, focused, commercial.

The ultimate art outsider, who had cut such an emaciated, alien figure for much of the previous decade, had physically rebuilt himself to take over the mainstream. The news reporter picked up on this new look, describing Bowie as “a future Dirk Bogarde in the making”.

“Under the tan and the teeth, the themes conjured up by his suit were still the same: alienation, a lost dream of the past and a sense of standing somewhere outside things”

EMI’s investment in Bowie – rumoured at the time to be between £10m and £17m – paid off. Both the album and the attendant Serious Moonlight tour surpassed all his previous outings (in seven months, he ticked off 15 countries, 96 shows and 2.6 million tickets). In search of a similarly oversized image, Bowie decided that “it would be fun to dress everybody up in some kind of costume… make it look a bit like Singapore in the 1950s”. Other reported visual references were the idea of a Mr Paul Newman-esque rock star and a negative photographic image of Little Richard.

Inspired by Mr Luis Valdez’s Broadway play Zoot Suit and a production of La Bohème at the Met, Bowie hired the costume designer responsible for both, Mr Peter J Hall, to realise this vision. “He chose all the materials and came to see how everything would look under our lighting,” said Bowie in the tour’s accompanying book. “The thing with stage costumes is they look really silly offstage. Like they’d fall apart. Put it onstage under lights and it looks good.”

Hall created a series of retro suits for Bowie in different shades and the same cut. High-waisted pleated trousers with a belt and striped braces, a one-button double-breasted jacket with piped lapels and a crescent moon patch on the breast pocket, an off-white collared shirt and an untied polka-dot bow tie. The suit came in powder blue, grey, lemon yellow, lime green and, as on this August night in Edmonton, Canada, a soft peach.

It was Hall’s first foray into rock music. His work was more commonly seen at the Royal Shakespeare Company, La Scala and the Met. The 1950s style Bowie tasked Hall with creating was already being gradually revived (The Face’s “Hard Times” feature, with its denim-and-quiffs visuals, had appeared in September 1982), but this reworking of the singer’s childhood decade was something more refined and dream-like.

In the videos for his Let’s Dance album, Bowie moved around the old colonies of Australia and the Far East, his style riffing on the disconnected ex-pats left in those places as the empire receded. Rather than the real 1950s of demob suits and man-made fibres, this was a world of Englishmen going slowly mad in the sun, dressed for a time and a lifestyle that no longer existed. It was as unreal and mannered in its way as his Ziggy Stardust persona from a decade earlier.

On the surface, Bowie’s 1983 reinvention was his move into the mainstream. But under the tan and the teeth, the themes conjured up by his suit were still the same: alienation, a lost dream of the past and a sense of standing somewhere outside things. It was just conveyed with more subtlety.

“When you reach your mid-thirties, there’s a period where you have to decide not to try and grasp frantically for the feelings of desperation and anger that you had in your mid-twenties,” he told the BBC reporter at Claridge’s. “And if you can relax into the idea that the mid-thirties is a nice place to be… the perspective changes.”