THE JOURNAL

Mr Freddie Gibbs was not invited to the Grammys this year, but he still showed up. Not in person, but by reputation. During a wildly ambitious, 15-minute Questlove-curated performance that paid tribute to the greatest names in hip-hop’s 50-year history and made even the normally stoic Jay-Z break into a wide grin, Gibbs’ name flashed on the screen behind the performers, alongside the names of other absentee artists from the genre.

“At least they included me in that,” says Gibbs, via Zoom from his music studio, wearing a plush Culture Kings robe and pouring himself drinks from a bottle of Casamigos tequila. A giant oil painting of his face hangs in the background. “They could at least have given me a seat. I could have sat next to Beyoncé or something. You know what I'm saying?”

Gibbs was a notable exclusion from “music’s biggest night”, but not just because of rap’s golden jubilee. At 40 years old, the rapper is at the top of his game and has a comfortable seat in the pantheon of rap deities, such as Black Thought, LL Cool J, Missy Elliot and many of the others who performed that night. He has five studio albums under his belt, as well as four critically acclaimed collaborations with Madlib and The Alchemist. Each of them is a rapping masterclass. The latest, $oul $old $eparately, is no exception.

Most in the industry, even Gibbs himself, would argue that his consistency as a rapper is nearly unmatched. His excellence is almost predictable, but all he has to show for it in terms of institutional recognition is a single Grammy nomination, a Best Rap Album nod for Alfredo in 2021.

That’s why Gibbs is not incentivised to fake humility. “I ain’t tripping,” he says. “It is what it is. I don’t think nobody put out a better rap album than mine. I think it’s just another case of me being underrated and I just got to work harder now.”

To that end, Gibbs is focusing his efforts on conquering another industry: Hollywood. He is launching a film production company with his manager and career-long partner, Mr Ben Lambert. This ambition, to work in film, is a relatively new one, inspired by the filmmaker Mr Diego Ongaro, who trained Gibbs as an actor to star in his 2021 indie film Down With The King. The film was loved by the few critics who saw it. The New York Times’ Mr AO Scott named Gibbs one of the best 10 actors of 2022, in a list that included Ms Michelle Yeoh, Mr Daniel Kaluuya and Ms Michelle Williams.

“I make music, but I’m a very multifaceted entertainer. I’m not just a guy rapping in his bedroom”

In Down With the King, Gibbs plays a jaded and alienated rapper, Money Merc, who has been exiled to rural New England by his manager to work on a new album. Surrounded by wilderness, the rapper has a career crisis. “Merc’s predicament is excruciatingly real, which is to say that Gibbs’ performance is as good as it gets,” wrote Scott in a review, praising Gibbs for a sensitive and nuanced portrayal. Gibbs had plenty of real-life experience to draw on for the role, but it would be a mistake to reduce the performance to mere auto-fiction.

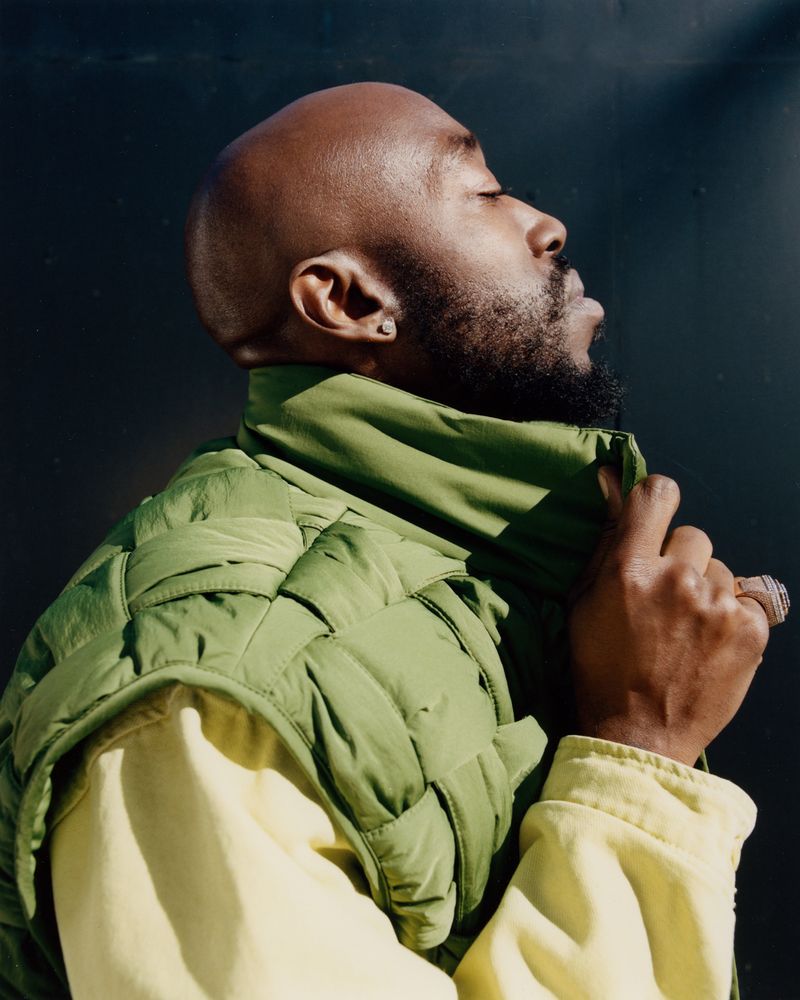

A week before our Zoom conversation, Gibbs is posing for his MR PORTER photoshoot inside a gilded mansion in the San Fernando Valley, complete with marble floors, elaborate frescoes, towering columns and impressive crystal chandeliers. Its palatial, Baroque-style exterior stands out in the neighbourhood. The houses that surround it, although just as big, have a more contemporary southern California architecture. Less grandiose. More adobes and bungalows.

Gibbs meets me in one of the dining rooms. He lives up the street, he says, and drives past this house all the time when he’s picking up his kids from school, dropping them off at piano lessons, fencing practice, music theatre. “So this is what it looks like on the inside,” he says, hands on his hips, looking out to the property’s lush garden.

He has been a resident of the Valley for 10 years and of Los Angeles since 2005, which is why many consider him a West Coast rapper, but he was born in Gary, Indiana, a small industrial city that is the home town of more than one legend. The Jacksons, as in Mr Michael and Ms Janet, also trace their roots back to that same rustbelt town. Unlike the Jacksons, Gibbs fell into the music industry incidentally, as a wandering child of Gary.

“I was a spectator of the sport,” he says. “I didn’t really know if I wanted to be a rapper. My homie had a studio in the hood. And he was one of the only people who had it.” Gibbs’ football career had fizzled out and he had been dishonourably discharged from the army after getting caught with marijuana. To make money, he dealt drugs and considered his career options.

“I knew I wasn't going to ever be a producer,” he says. “I can’t play no fucking music. That wasn’t me.” He wasn’t going to be a DJ either. “All the drug dealers wanted to be rappers. All the girls wanted to be around the rappers and the drug dealers.”

So, he became a rapper. It didn’t take long for him to meet Lambert, who was, at the time, an eager young intern at Interscope Records who wanted to secure a full-time job at the label by signing new talent. Lambert, who now goes by Lambo, would become his manager for the next 20 years, although their partnership appears to transcend that of a typical artist-manager relationship.

“We both came into shit like this as babies,” says Gibbs. “I was young. He was young. I was like 21. He was like 19. And we was just trying to find our way through the industry. We learnt a lot together and we just grew together, trying to take care of ourselves and feed our family.”

“I’m pretty sure it’s easy for Kendrick, Drake or J Cole to walk into a Hollywood movie studio and demand a role. I was never in that position”

Lambo found Gibbs on a music blog and convinced him to come out to California to sign with Interscope. Gibbs left the label before he could drop an album, but the wheels of history were already turning in a certain direction. “Lambo saw potential from the beginning,” he says. “I didn’t know I could really rap. I didn’t think my raps were good enough to be on a national or global level, but he told me. He put that in me and once I got that confidence. It was a wrap.”

Did he see potential in Lambo as well?

“I mean, he was just white, so I knew he could get me far,” says Gibbs. “Nah, Lambo is definitely one of the smartest guys I know. He’s such a big fan of the music. He’s kind of like a rap historian. He knows the ins and outs of the shit. He’s really been listening to it his whole life. Not like most kids where he’s from who just listen to it for pleasure. He dissects the music, dissects the artists. The art of being a music executive, he mastered that.”

It was Lambo who encouraged Gibbs to work with Madlib and The Alchemist on albums that put him on the radar of every nerdy rap music blog at the time. In the years since, Gibbs has released nine music projects, a sunglasses line with LA brand Akila, a capsule collection with the streetwear brand Carrots, multiple wine collaborations, collected a couple of IMDb credits and on and on and on. Gibbs is intentionally and calculatedly diversifying his brand.

In recent interviews, including this one, he has talked less and less about being a rapper and more and more about being a performer. Gibbs talks about the “rap game” with some measure of fatigue and disaffection, alienated by rap beefs and social media posturing.

“I got to kind of remove myself from a lot of that shit and focus on just being in the business of me,” he says. “Yeah, I make music, but I’m a very multifaceted entertainer. I’m not just a guy trying to make a rap song or rapping in his living room or bedroom or something like that.”

The business of being Mr Freddie Gibbs is booming. He is working on his sixth album and he and Lambo are building a “multifaceted multimedia company with music, film, clothing, all of that stuff, and bringing it all under one house”. That house is Rabbit Vision, a production company named after one of his songs (the music video for which he directed).

Down With The King did not mark the beginning of Gibbs’ interest in film or being a filmmaker. In 1994, his father took him to see Pulp Fiction, against his mother’s wishes. That’s when he fell in love with Mr Quentin Tarantino movies. “I think that was the first one I ever saw,” he says. “But then I saw From Dusk Till Dawn and I went back. I’d love to be in one of his films. If he hit me, I’m on the way. I’d stop recording the album just to be in his movie, for real.”

The pivot from rapper to actor (and, more infrequently, from actor to rapper) is not a novel one (see LL Cool J, 50 Cent, Queen Latifah, Ice-T). Rap is a theatrical genre and as obsessed with glamour and wealth as Hollywood is. For Gibbs, the question wasn’t if he were capable of being an actor; it was about whether the stewards of cinema would let him in.

“I’m pretty sure it’s easy for Kendrick [Lamar], Drake or J Cole or somebody like that to go walk into a Hollywood movie studio and demand a role,” he says. “I was never in that position. I wasn’t an A-list rapper when I was going to these auditions. It was like, ‘Who is this guy? Who?’”

Down With The King was a springboard. It took Gibbs to the Cannes Film Festival or, in his words, from high school to the pros. Offers have been rolling in ever since, he says. He even showed up in an episode of the TV comedy Bust Down last year, but he is being judicious about his next role.

“The kid in me that just only enjoyed being a rapper, that’s done. He’s out of there”

Every decision Gibbs has made about his film career has been highly intentional. “I want to mould my film career the same way that I moulded my rap career,” he says. “I was real choosy in my rap career in things that I did, so I got to be the same way in my film career so I can have that same longevity and I can work till I’m 85 like Samuel L Jackson.”

Many rappers who move into acting get typecast in certain roles. They are forced to play gangsters and rappers. Gibbs doesn’t want that for himself and with Rabbit Vision, he’ll be able to have more control over how his acting career unfolds. “You ain’t about to see me on fucking Tubi,” he says. “This one rapper that had beef with me, this motherfucker died in his own movie. I’m like, ‘How you die in your own movie you stupid motherfucker? How you play yourself, die in their own movie?’”

Gibbs wants to make comedies, dramas and documentaries. He wants to play doctors, lawyers and preachers. He wants to tell stories about underdogs, like himself. Rabbit Vision, he says, is an underdog company. The world still knows Gibbs as a rapper first. He is trying to change that, but it doesn’t mean he’s leaving music behind.

“I could make a film and drop an album with it,” he says. “That’s a goddamn soundtrack. The musician in me will never die, but maybe the kid in me that just only enjoyed being a rapper, that’s done. He’s out of there.”

Really?

“Yeah, he’s done. Because he had to grow. Like I said, he had to learn how to be a boss.”