THE JOURNAL

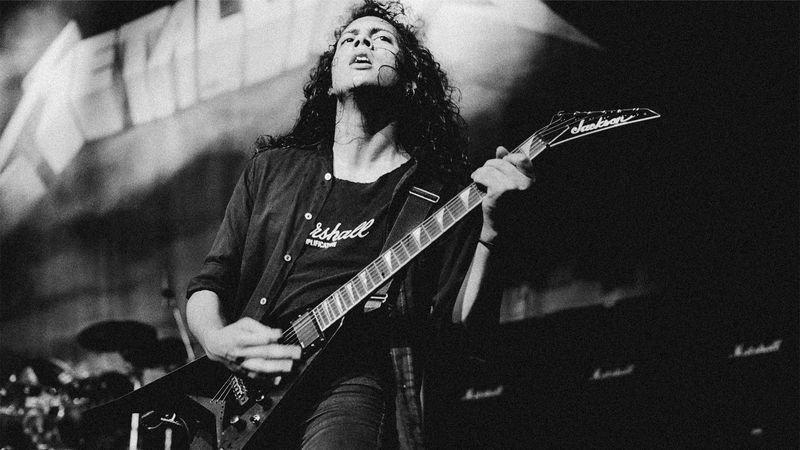

Mr Kirk Hammett of Metallica at the Poplar Creek Music Theater in Hoffman Estates, Illinois, 13 July 1986. Photograph by Mr Paul Natkin/Getty Images

There’s a clip of a young Mr Kirk Hammett talking about how much he dislikes fashion. “I just like dressing comfortable,” says the permed Metallica guitarist in a Glenn Danzig tee. Next to him, Mr James Hetfield’s lioness curtains frame a sleeveless Cramps shirt that looks almost sprayed to fit. “There’s a lot of people who get really involved in new trends and fashion,” Hammett goes on. “But what’s the point? We dress for ourselves.”

As much as they might hate to hear it now, Metallica’s silhouette has impacted generations of dressing, convincing fellow metallers Armored Saint to drop their own medieval torture-chamber look and sparking viral James Hetfield-style memes in 2008. Metallica are even credited for inadvertently spearheading the thrash metal subculture, thrashion (think ripped jeans, tight denim, studs and leather sweatbands). The four-piece – who are rereleasing their self-titled 1991 album this week, featuring covers by modern-day superfans such as Ms Phoebe Bridgers and St Vincent – moved the needle for both high-end and high-street trend cycles, helping a wave of satanic-rock worship find its way into the ateliers of Paris and New York. Overarchingly, the story of Metallica’s reluctant style influence speaks to the long shadow heavy music continues to cast over the fashion industry.

You could call the early 2010s a kind of year zero for metal’s big fashion crossover. A lot has been written about Mr Nicolas Ghesquière’s 2012 collection for Balenciaga, which repurposed Iron Maiden’s logo font (itself a riff on original poster art for Mr David Bowie) across a black satin sweatshirt. The following year, Mr Kanye West commissioned Grateful Dead’s merch designer Mr Wes Lang to create morbid, metal-inspired doodles for his Yeezus tour.

And once the high-fashion world sets a new temperature, the high street follows: suddenly and inexplicably fast-fashion brands were flogging bootleg Black Sabbath tees, Nirvana’s In Utero crucifixion scene and even Burzum merch. Burzum – you know, the neo-Nazi arsonist who murdered his own bandmate.

Left: Vetements AW16 runway, Paris, 3 March 2016. Photograph by Ms Kristy Sparow/Getty Images. Right: Balenciaga AW12 runway, Paris, 1 March 2012. Photograph by Retna/Avalon Red

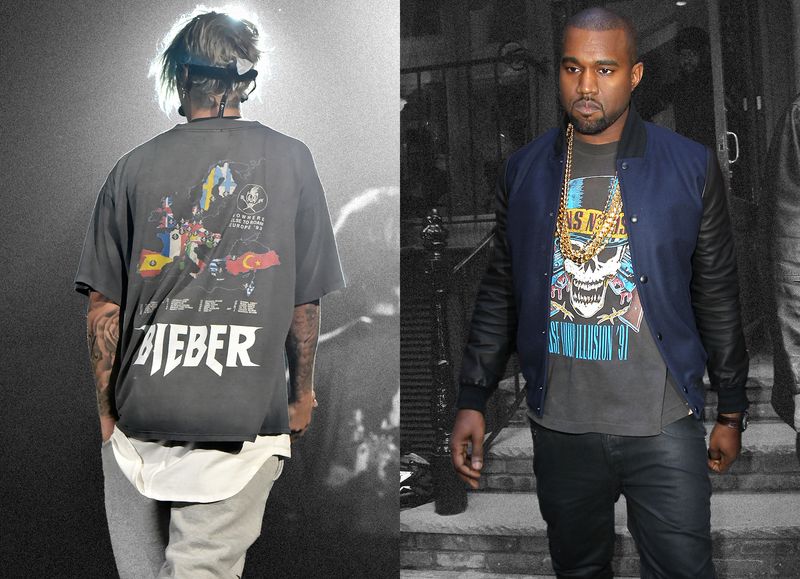

By 2016, feeds were flooded with celebrities wearing pentagrams, black metal type and the logos of Beelzebub’s favourite bands: Slayer (Ms Kendall Jenner), Anthrax (Ms Jessica Stam), Mötley Crüe (Fergie) and Guns N’ Roses (Kanye). The same year, Fear of God’s founder Mr Jerry Lorenzo was commissioned to design the rail for Mr Justin Bieber’s world tour. The runway was dialling celebrity culture to 11, and the high street was demystifying the runway.

By the time it was luxury’s turn to swing again, Parisian label Vetements added its own typically situationist twist to the pile on. For the brand’s SS16 line, founder Mr Demna Gvasalia put necrophiliac fonts you’d usually see on the sleeve of a Bathory EP next to the brand’s usual familiar reappraisals: the DHS logo, the Ikea bag and the golden arches. It was a way of putting the mainstream’s piggybacking in its place again: you can’t claim a rebellion if you are selling it in bulk.

Over in the US, Supreme turned metal remix culture into an official band collab, partnering with Black Sabbath on a one-off SS16 line spanning tees, parkas, caps, a hockey top and a rug. But the streetwear label wasn’t alone in crossing industry lines in this way. Since founding his eponymous brand in 2010, London designer Mr Yang Li has found magic in this difficult grey area, inviting metal innovators such as Swans’ Mr Michael Gira and Godflesh’s Mr Justin Broadrick to serenade his Paris Fashion Week audiences. For his project Samizdat, Li designs merch for a fictional noise band of the same name. In 2018, he asked New York noise artist Pharmakon to torch the skies above Vancouver’s luxury retail space, the Leisure Center.

The looks for the event were directed by Li’s show partner, Ms Ellie Grace Cumming. Alongside her role as AnOther Magazine’s fashion director, Cumming works with legendary post-punk musicians such as Mr Nick Cave and Mr Bobby Gillespie, and is herself inspired by the natural fashion sense of metal and heavy music movements. “[Industrial pioneer] Blixa Bargeld was our first ‘gig’ in March 2017 at Palais de Tokyo – we broke the system by having [models] in the audience while he played a set, replacing the typical catwalk runway show,” she explains of the project.

Left: Mr Justin Bieber on stage at the Staples Center, Los Angeles on 20 March 2016. Photograph by Mr Jeff Kravitz/Getty Images. Right: Mr Kanye West in New York, 5 April 2012. Photograph by Pacific Coast News/Avalon Red

For Cumming, the fantasy and authenticity of metal offered an escape from the high-street logomania of the mid-2010s, when the lines between fandom and mass culture started to blur. “The metal scene had a calm purity: you knew where you were, in the shadows, choosing a different life,” she says. “The 1980s music scenes, whichever genres, all had their own strong visual identities. For me, it was the consideration that went into creating these looks: leather, lace, fishnet and velvet – my favourite fabrics. They took a lot of influence from Victorian menswear: white tailored shirts, waistcoats, mixed with Umbro shorts and fishnets. It was the mix, the re-appropriation and interpretation, the outlandishness of the artwork of graphics and the merch. A lot of people then had very little money, but would put their outfits together through purchases at thrift and charity stores, every piece specifically chosen and cherished.”

Dr Samuel Thomas is a professor in American studies and critical theory at Durham University, who is writing a book about metal’s wider cultural impact. In his view, the music underground has always exchanged ideas with the fashion world – it’s an energy that transported the tie-dye radicalism of San Francisco’s hippies into the homes of The Simpsons-era US, for example. Commercial crossovers are actually encouraged by some metal fans, he says. “For a lot of metalheads, the fact that metal fashion, metal gear and metal logos are part of the fashion industry is something that could bring more people into particular scenes, and perhaps provoke more creativity.”

For Thomas, it’s important to look at the logos as things that can’t be owned or claimed by any one particular subculture or group. If a popular logo belongs in a history book, he says, then it belongs to everyone – and no high-street logofication can ever change that.

“I think it’s legit to talk about the Iron Maiden logo now as a design classic – metal is over 50 years old now,” he says. “A few years ago, I went to an exhibition in Birmingham [UK] called The Home Of Metal, which marked the 50th anniversary of the first Black Sabbath record. The show explored aspects of metal fashion, metal culture, metal music, and had a great sociological depth to it. It’s fair to sort of think about all of that in terms of cultural heritage.”

Beyond the 2010s and well into the future, the relationship between fashion and subculture will continue to oscillate in these ways, negotiating rifts and complexities between personal experience, community, the art and craft of fashion and broad appeal. Metal and heavy music has left an indelible mark on low and high fashion, finding new audiences and bringing fascinating, passionate and primitive sounds into window displays and onto the runway.