THE JOURNAL

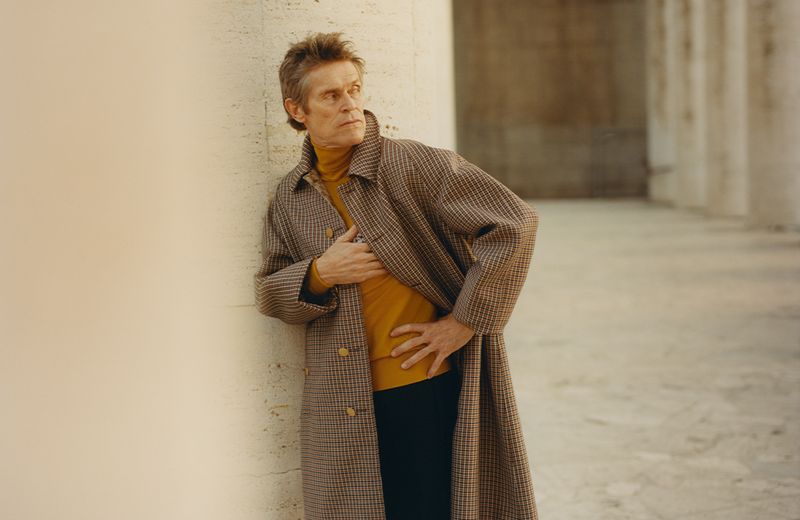

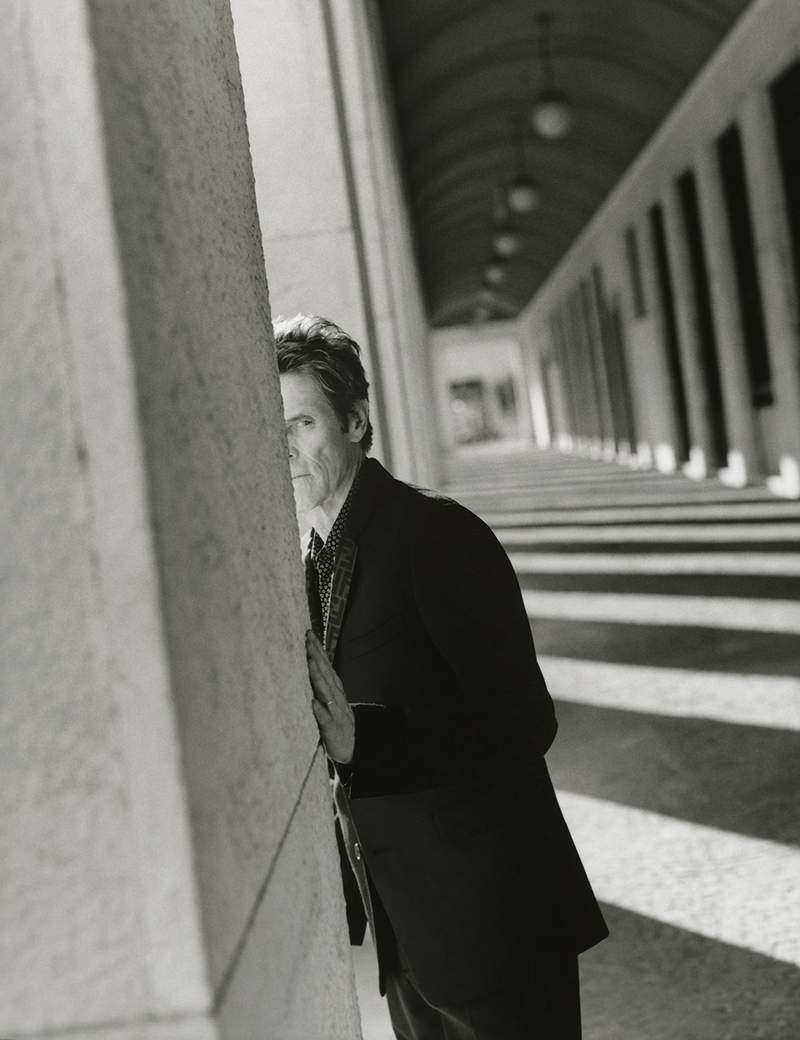

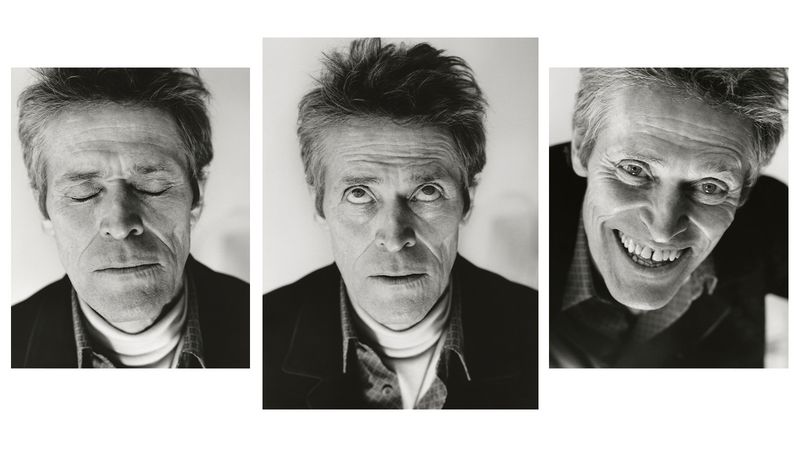

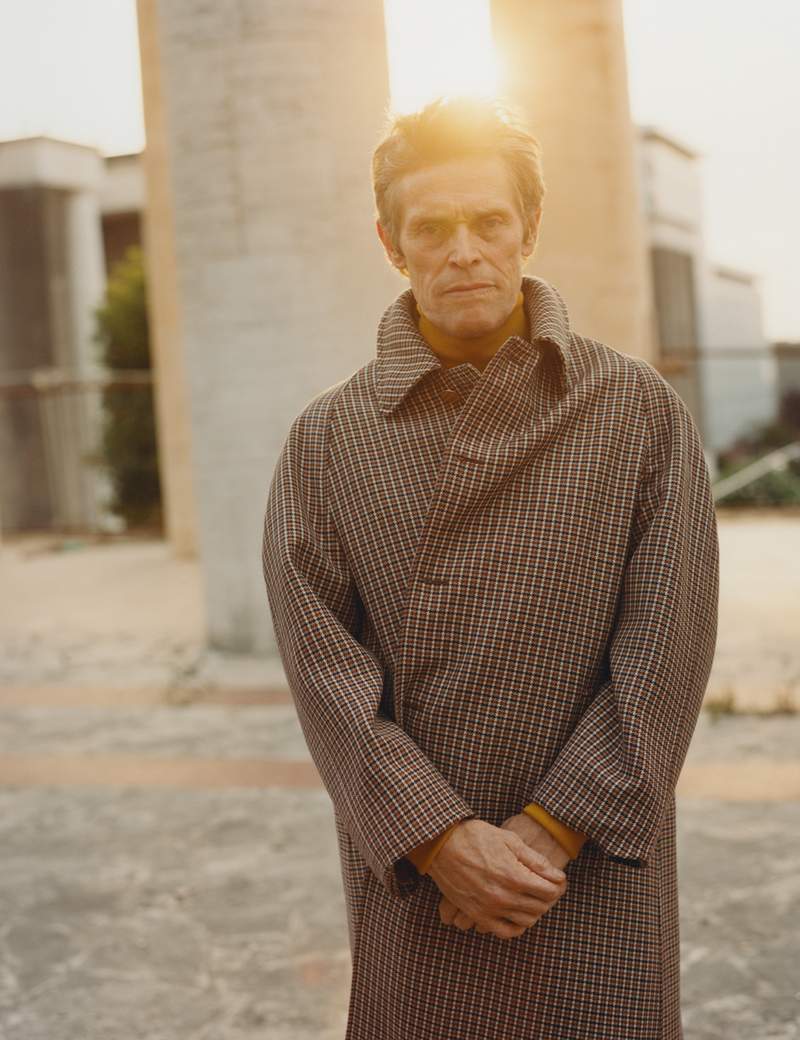

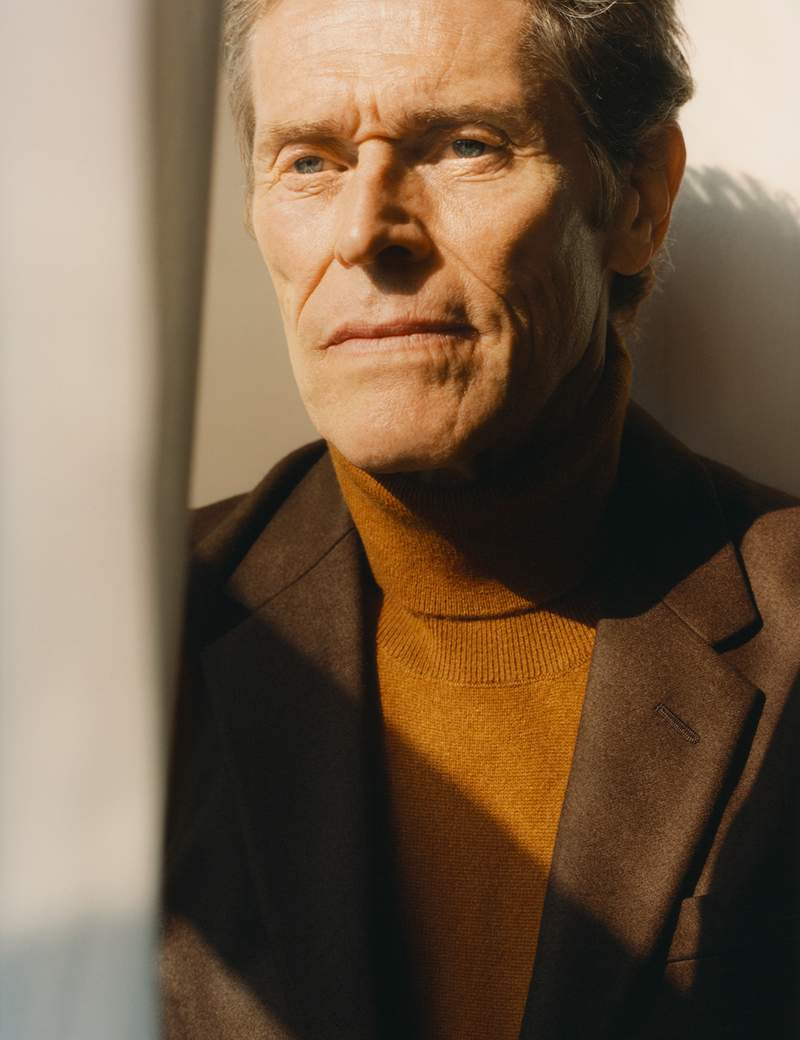

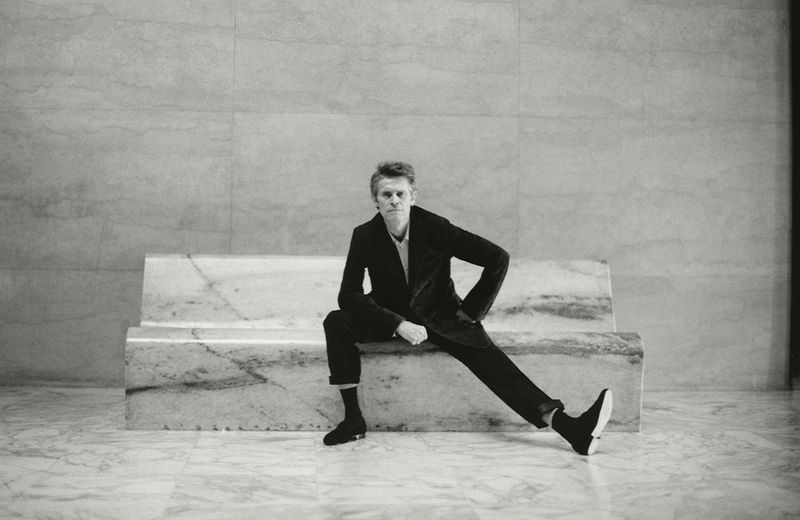

Mr Willem Dafoe doesn’t look or sound like, well… “Like a normal person?” he yells. Two laugh lines, as deep as a ventriloquist dummy’s, frame the question. His grin is wicked, mouth wide as he pulls his extraordinary face closer to mine. “Say it!” Mr Dafoe demands, cackling. He’s in a seated lunge as we chat, his right knee hovering a few inches off the ground as he explains why he’s here, in a room at the Ritz-Carlton hotel in Toronto, speculating about his normality.

“I use these interviews sometimes to – it’s really stupid – but to see how I feel,” says Mr Dafoe. He smiles, but his eyebrows travel upwards, as if distancing themselves from the earnestness of his statement. “I try to articulate really deeply why I do what I do and put it out there so I can look at it and say, ‘Is that true or not?’”

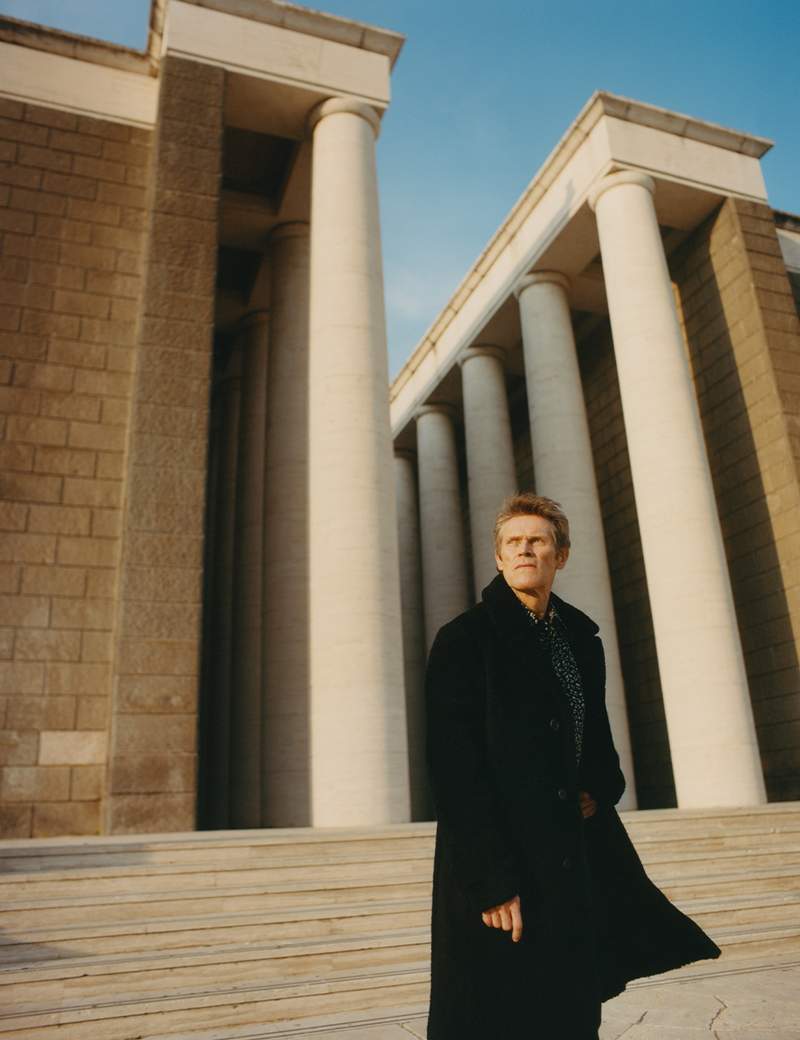

What Mr Dafoe puts out there – on screen, at least – is defined by a sense of controlled menace. Even if one of his characters is as chaotically benevolent as Mr Dafoe seems to be in real life, it tends to feel impermanent. Like, at any moment, as Mr Dafoe puts it, with a creeping smile, “I could be bad.” This delightfully unsettling energy has earned him four Oscar nominations, for his work in Platoon, Shadow Of A Vampire, The Florida Project and At Eternity’s Gate. It’s made for striking renditions of a stump-toothed psychopath (Mr David Lynch’s Wild At Heart) and God’s only son (Mr Martin Scorsese’s The Last Temptation Of Christ). It’s been channelled in three Mr Wes Anderson movies (The Life Aquatic With Steve Zissou, Fantastic Mr Fox and The Grand Budapest Hotel, plus the upcoming The French Dispatch). It’s earned large pay cheques in two superhero franchises (Spider-Man and Aquaman.)

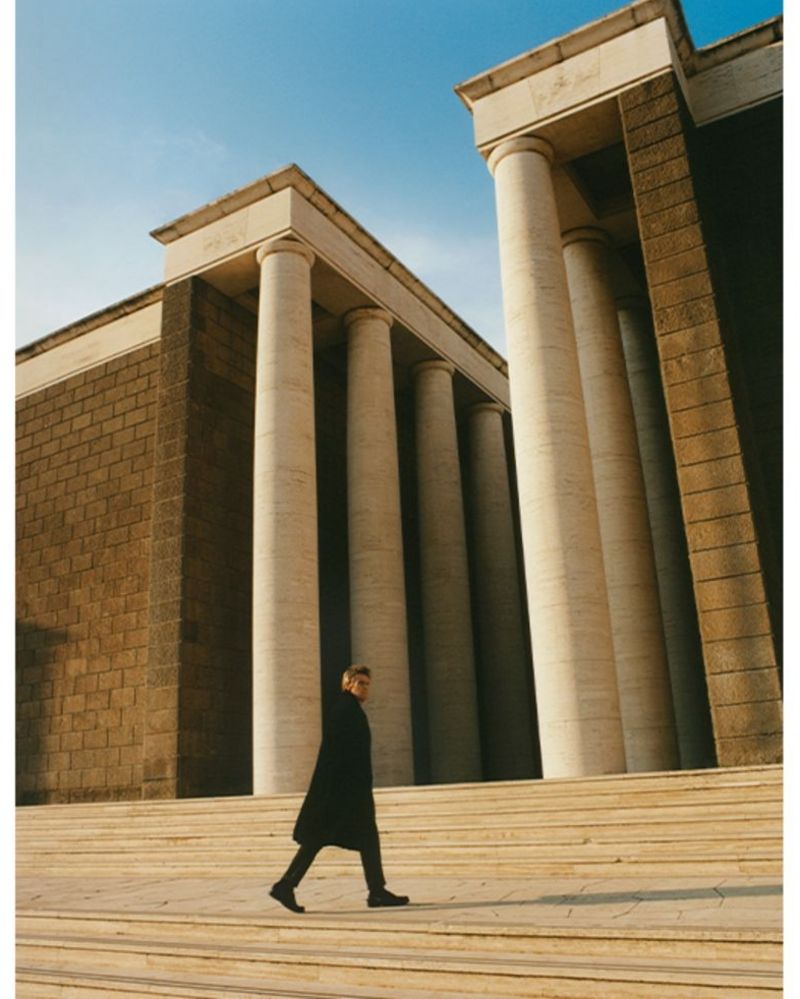

It’s also present in Mr Dafoe’s two new – suitably weird – roles in movies that screened at the Toronto International Film Festival, which is where we meet. There is Mr Rob Eggers’ brilliant black-and-white two-character psychosexual movie The Lighthouse, in which Mr Robert Pattinson and Mr Dafoe portray lighthouse keepers who can’t decide if they want to kiss or kill each other. And then there’s a supporting role in Motherless Brooklyn, Mr Edward Norton’s 20-years-in-the-making adaptation of the noir novel by Mr Jonathan Lethem. (Mr Norton optioned the novel before the release of his directorial debut, the 2000 romantic comedy Keeping The Faith, and began developing the film in 2014.)

The day before, Mr Norton told me he’d been modelling his own path on Mr Dafoe’s for even longer than he’s been working on this movie. “In the 1990s in New York,” says Mr Norton, “I was getting involved in my theatre company. Mark Ruffalo and Philip Seymour Hoffman were there. Willem was one of those pole stars for us, because he was the guy who had helped found the Downtown New York theatre company The Wooster Group, stayed true to it and became a great character actor and a movie star. Willem made you think, if you could have a career like that, that would be the best you could hope for.”

Now 64, Mr Dafoe says all this was possible because of his approach to life. It entails risking vulnerability in order to expose truths and the beauty of getting outside yourself. It involves being “psychotic for engagement”. It’s about “working with people he is in love with” and “being a guinea pig” on behalf of the audience and “coming into scenes through the back door” and “pranayama alternate-nostril breathing exercises”. “I aspire to be an everyman,” says Mr Dafoe. “And somewhere I believe that all characters are in us. It’s a little like the Walt Whitman thing. I don’t know what the quote is, but the idea that you are multitudes.” Then he excuses himself to go to the restroom, where he evidently considers how all that just sounded.

“You think of it being printed,” the actor says when he returns, pulling up his yoga-honed knee and tilting back in the chair. “And you think, f*** this guy.” Like the rest of Mr Dafoe, the self-awareness is charming. He continues: “Using an interview to figure out how you feel is weirdly narcissistic.”

Has Mr Dafoe ever read a profile of himself that caused him to recalibrate his life? “No,” he says. Did he come into this interview with an objective? “No,” he repeats, confidently. “No,” I say back. Then Mr Dafoe cranks his head towards his right shoulder and the corners of his mouth turn down, transforming his face into the demented mask of a silent-film character. After a moment of contemplation, he reverts to a look that passes for normal on him and downgrades the certainty of his answer. “I don’t think so,” he says, head bobbing slowly.

Though we’ve watched him do it in every film he’s been in, it’s moving to witness, in real life, this magnificently confident icon of screen weirdness strive for genuine reflection from within in an artificial set-up. “When you get something held up to you and you see something, yeah, that runs deep,” says Mr Dafoe. “I believe that could happen.” (“That” evidently meaning “self-reflection achieved through reading a profile of himself in a fashion magazine”.)

“I find great power in submission,” Mr Dafoe murmurs. “It liberates you.”

And while you could draw some colourful conclusions from his literal words – and the purr in which they’re delivered – Mr Dafoe is talking about working with strong directors, such as The Lighthouse’s Mr Rob Eggers. “There was one time that I gave him a note he didn’t like,” Mr Eggers says of working with Mr Dafoe, who approached the director about working together after seeing his first film, The Witch. “When Dafoe’s eyes are blazing like that at you, you have to kind of take it with a pinch of salt. I was like, ‘Look, Willem, you’ve got to take the note.’ And I couldn’t let him know that I’m thinking, ‘Holy shit! The Green Goblin is giving me the stare of death.’ But then afterwards he was like, ‘You were right.’”

Of course, there’s also power in dominance. In The Lighthouse, Mr Dafoe plays a weathered lighthouse keeper who is – and this is quite an understatement – quite possessive of the titular lighthouse. His co-star, Mr Robert Pattinson, spends much of the film being ordered around by Mr Dafoe and surreptitiously masturbating. Then things get much, much weirder. “There was something which I found quite intimidating about him at the beginning of it,” Mr Pattinson says of Mr Dafoe, a week after Toronto. “I remember the first couple of dinners we had together, I could barely speak. And I was like, God, why can’t I get it together?”

“Rob Pattinson worked very differently from me,” says Mr Dafoe. “But I made no judgement on it because he had a different job. And also, I don’t need him to work the way that I work. If I want to, I can work the way he works. He’s a more reactive character. He’s acted upon. So, it was very different.”

Different how? “He doesn’t like to rehearse,” says Mr Dafoe with the twisted brow of bewilderment. “He prepares, but he prepares by himself.” (“I sort of used the rehearsal process [to try and] see all of Willem’s cards, which frustrated him,” says Mr Pattinson. “It’s quite competitive, the two parts, and so I guess I was trying to cheat as much as I could going up against someone like Willem. As soon as I could see that he knew what I was going to do, it would make me really sad. I was trying to surprise him as well as myself every time. He seems to be able to do a scene in an infinite number of ways. I feel like I’ve only got maybe five ways to do it.”)

According to Mr Eggers, Mr Dafoe would rehearse at full power, the way it’s done in theatre productions. And when they got to the end of the script, Mr Pattinson says, Mr Dafoe would immediately shout, “Again!” During his off-time, Mr Dafoe was holed up in his fisherman’s cottage in Nova Scotia, working on what Mr Eggers calls his “faux-Shakespearean dialogue”, practising Ashtanga yoga and preparing “nearly vegan” meals.

Mr Dafoe seems bemused by his co-star’s approach. “He’s not interested in craft, I think,” he says. “He wants to throw himself into deep water and he feels like it will only be true if he’s drowning. Which, for this role, is perfect because that’s the state he’s going to be in. For me, that seemed wacky. But I’m not trying to judge. He has a good sense of the visual, of what’s needed in a close-up. Sometimes he’d beat himself up so bad. He’d stick his fingers down his throat, things like that.”

Mr Pattinson laughs as he recalls coughing up the performance. “I would sneak off into a corner and gag, away from Willem. I think everyone feels very emotional when they’re throwing up, and it’s quite a nice little trick to get there. He didn’t know I was doing it until one scene where I was absolutely forced to do it in close proximity.” (In the scene, Messrs Pattinson and Dafoe’s characters are drunk and losing their minds, and Mr Dafoe lies on Mr Pattinson’s chest. “Before every take,” Mr Eggers says, “Rob was sticking his fingers down his throat. Willem gave me a look as if to say, ‘If this guy f***ing pukes on me…’ ”)

This brings to mind the story Mr Dustin Hoffman tells about working on Marathon Man with Sir Laurence Olivier. Mr Hoffman was experimenting with the method, wherein an actor tries to get as close to the part as possible. The film features a torture scene in which Mr Hoffman’s character is, among other torments, forced to stay up all night. To prepare, Mr Hoffman did not sleep, instead partying to make himself as exhausted as possible for filming, which he proudly revealed to Sir Laurence. “My dear boy,” Mr Hoffman says Sir Laurence told him, “why don’t you just try acting?”

“Willem and I talk about that all the time,” says Mr Eggers of comparing Mr Pattinson’s process to what he calls “that Marathon Man thing”. He also notes that “Rob likes to diminish his talent, preparation, rigour and ability”.

Here’s how Mr Eggers describes Mr Dafoe: “He’s Willem f***ing Dafoe.”

“You don’t want to be Willem Dafoe,” says Mr Willem Dafoe. “Or whoever I think Willem Dafoe is.”

Who does he think “Willem Dafoe” is? “Personality is an illusion,” he says. “It’s changing all the time.” His palms open to the chandelier at the impossibility of carrying a reliable set of traits in a lone human-shaped receptacle. “You don’t want to be a slave to a narrative or a creation of yourself that you’ve made,” he says. “Then you start to protect that thing you’ve created, and all your energy goes towards protecting this thing that isn’t real. But for sanity, we agree on certain things. That’s normal. Otherwise, we wouldn’t know where we lived, or we’d want a different partner every night or something, you know? Some people want that anyway.” Mr Dafoe crosses his arms in surrender, indicating that, you know, he’s not judging.

But even if he isn’t cultivating a persona, Mr Dafoe still has a distinct brand. Mr Pattinson gleefully describes him as a “reformed – no, a turncoat demon”, as in “a demon who has forsaken his demonic ability to cause pain, instead working in service of mankind”. Mr Dafoe admits some of that projected power is put on, or at least an add-on. “When you’re a kid living in Alphabet City in the 1970s, yeah, you start to play a role, you know?” he says of moving to Manhattan from Appleton, Wisconsin. “You pick up a kind of tough-guy New York thing. Now I’m listening to myself and I’m self-conscious.”

When Mr Dafoe thinks about it, it all seems a little silly, the way his profession did to him when he was a kid. “I was repelled by certain aspects of being an actor,” he says. “The narcissism, the me, me, me-ness of it, the career stuff, the glamour stuff. I thought, grow up! And I thought I would grow up and do something else. But I never got around to it.”

Alongside every other singular Mr Willem Dafoe characteristic, it – the self-awareness gleaned through magazine features, the danger of his contained force, the devilish and beatific face, the submission and the dominance – adds up to something uncanny. He simply seems too containing of multitudes to be someone ordinary.

I thought I would grow up and do something else. But I never got around to it

I don’t know a better way to explain who Mr Willem Dafoe is than to let Mr Eggers tell this story about him, which took place during the rehearsal period for the wet, literally freezing, “miserably fun” 32-day shoot for The Lighthouse. “I’m walking to dinner in Halifax, maybe with my brother,” says Mr Eggers. “We hear a homeless person screaming. And we’re ignoring it, but the screaming is getting louder and louder. We’re both thinking, f***. Let’s just get to the restaurant before we have some weird interaction with this schizophrenic man. He sounds scary, a little bit scarier than we would like to contend with that night. And, of course, it’s Willem Dafoe. He’s running down the street, screaming, wearing leather pants and he jumps on my back. I mean, he’s not normal, but he’s quite normal. Well-adjusted and thoughtful and so f***ing generous. You know what I mean?” I do.

With all this in mind, I finally ask Mr Dafoe to refute the statement he had wanted me to make. Does he think he seems like a normal person?

Mr Dafoe shrugs. “I’m always shocked that people recognise me as much as they do,” he says. “So, clearly, I’ve got a distinctive face. You’re conscious that certain things just don’t wash. They look wrong. I just know myself enough to know that there’s no reason why I can’t fit in anywhere.” A haunted lighthouse. New York City. Appleton, Wisconsin. A conference room in the Toronto Ritz-Carlton. A pair of leather trousers worn while scaring the shit out of his director.

Still, when we finish talking, Mr Dafoe issues a directive as he walks away. “Make me look good.”

The Lighthouse is out 18 October (US); 31 January (UK).

Motherless Brooklyn is out 1 November (US); 6 December (UK)