THE JOURNAL

“One of my favourite sailor jokes is from a captain I work with,” Mr Lee Meirowitz says. “There’s a kid who says, ‘Mommy, when I grow up, I want to be a sailor.’ And she says, ‘Well, honey, you can’t do both.’”

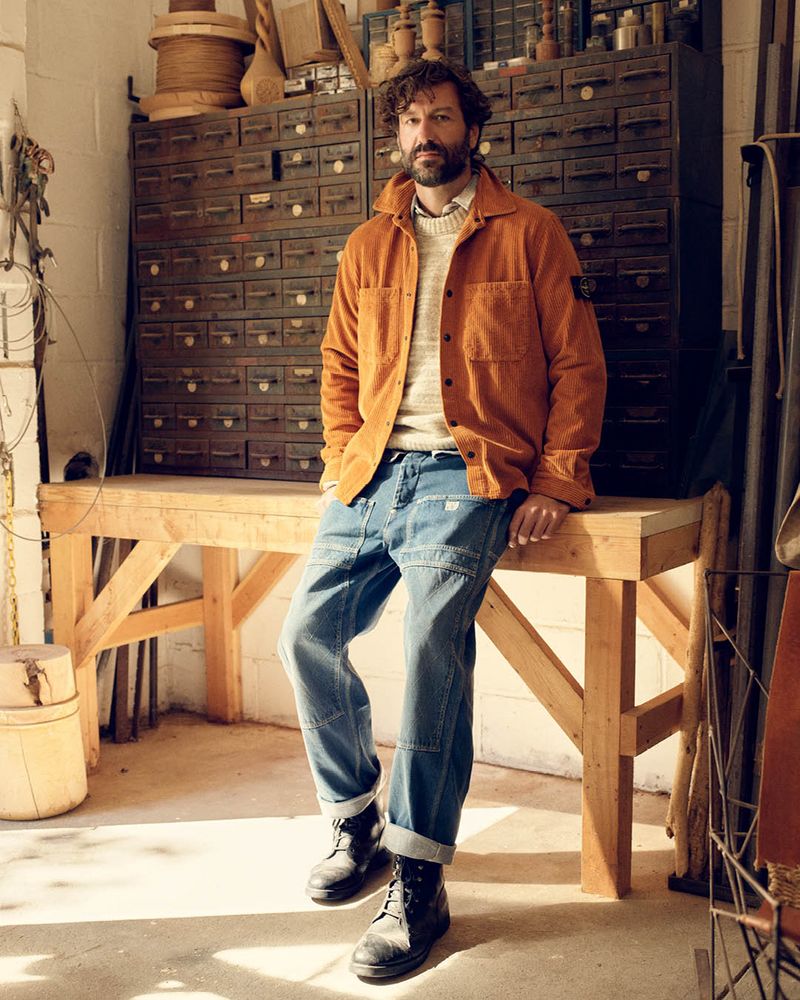

The men profiled for this piece, seen here wearing the latest from Stone Island, have managed to do a good amount of growing up between stints on the open seas. They’ve sailed to distant shores, pursued passions new and old, perfected their crafts and discovered themselves along the way. Wherever life took them, they have all returned to the place they feel most at home: the ocean.

The lure of the water and call of the wind has been an intoxicating combination for countless years. It’s no wonder that, despite advancements in maritime technology, the rudimentary act of harnessing the breeze with sheets of canvas and some rope has never lost its appeal. And it continues to attract new generations of sailors season after season.

Meirowitz, 39, is a former professional surfer and teacher who spent the last two summers working on an 80ft wooden schooner out of Newport, Rhode Island. He didn’t bring much experience to the gig, just a few excursions on a Hobie Cat in Montauk (think of a small sailboat just short of having training wheels). When asked about his strengths during the job interview, he was quick to respond. “I can talk to anyone,” he replied. “I bring a really good energy that makes people smile and feel comfortable.” When the inevitable weakness question came up, he didn’t miss a beat. “Well, I don’t really know how to sail.”

Luckily for him, his charm and confidence were sufficient enough to land him a spot on the ship, where he was provided with on-the-job training.

“Every boat is different, and you have to learn how to sail each one specifically,” he says. “But it’s really like riding a bike. It’s one of those things where, once you learn how to do it, you’ll keep it with you the rest of your life. I’ve trained on different types of boats, so I can consider myself a sailor. I’m pretty comfortable with sailing just about anything now.”

Meirowitz is no stranger to the life aquatic, having grown up on the North Shore of Long Island. “It was always my goal to one day get a centre console [boat] that I could take out spearfishing,” he says. “Now, I’d rather have a sailboat just to be able to zip around down to the Caribbean for the winter. I got bit by the bug. I’m stuck with a very expensive hobby.”

This newfound pastime has led Meirowitz to cross paths with other like-minded sailors, such as Mr Sammy Hodges, 33, who is also based in Newport – albeit loosely, given his wandering ways.

“I’ve lived in a lot of different places. I feel like I’m based on travel,” Hodges says. The professional photographer is also a freelance gun for hire around shipyards, coaching sailing teams, delivering boats throughout the Caribbean and competing in regattas all over the country. We caught him just before he took off for a month in Spain, where he’s set to film a documentary on the first American woman to sail around the world in the Global Solo Challenge.

The Georgia native is a self-described “coastal cowboy”, evident by the rugged boots he’s repped around marinas since he was 15 (they’re on their fifth resole). “I have kind of an interesting, funky style,” he says. “People laugh because I’ll walk through the boatyard in cowboy boots and everybody else is wearing flip-flops. I’m just going to dress like me and not really care.”

Hodges may have a singular sense of personal style among sailors on the Eastern Seaboard, but there’s no denying he’s cut from the same cloth as any old salt.

“Everybody speaks the same language, we all love the same thing,” he says. “And when you’re out there with a good crew that knows what they’re doing, you don’t really even have to talk; it’s kind of one organism.”

A solid crew is what undoubtedly sets a ship apart, especially during breakneck regattas experiencing the same relative conditions. A well-crafted workhorse engineered and built to perfection can only get you so far; it’s the eclectic mix of sailors from all backgrounds that creates the beating heart of a ship.

“People have different traits or personalities that make them more suited for a particular role on the boat,” Hodges says. “Whether they’re a thinker or a tactician, a navigator or engineer, a sail trimmer or a driver. Everybody has a niche based on who they are as a person. It really helps if you can put the right ones together. And you need the right kind of leader, too.”

Mr Zyggy Beatty is one such captain. “Zyggy is one of the most relaxed people I’ve ever sailed with,” Hodges says. “He’s very chill, even when shit is hitting the fan. He’s very much, all right, we need to do X, Y, and Z all while it’s blowing 35 knots, we’re in the middle of a squall, the sail is coming down and all this other shit is happening. I can’t ever imagine him being rattled. That's so important in a captain.”

When we spoke on the phone, Beatty, 36, was on his way to bow hunt elk in Idaho, a world apart from his home base of Saint Martin where he grew up on sailboats, fully immersed in the marine industry.

“Sammy has become one of my first calls, for sure,” he says. “I like guys on my crew to have a good attitude, who aren’t late for their watches, who are going to show up and do their job. It seems simple, but it’s becoming harder and harder to find.”

Beatty is hardly the weathered sea captain you’d expect from the pages of Melville, but he’s no less seasoned when it comes to assembling crews and leading them with conviction and hard-earned expertise. Despite spending his earliest days on the water, making a living on tugboats and barges, he still had to work his way up in the world of competitive sailing.

“I was at a point in my life where I was on the more commercial side of the marine industry, not the sailing side,” he says. “I was going to go one way or another. When I left home, I sold everything, grabbed a backpack, had like 50 bucks in my pocket and jumped on a boat that was sailing across the Atlantic. That was my first transatlantic trip. I’ve done another five since.”

Establishing himself as a professional sailor wasn’t a given at this point. “I wasn’t really sure how I was going to make it work, but I knew I was going to,” Beatty says.

And he did, through a mix of sheer grit, an unwavering love of the water and maybe a little luck. After all, sailors are nothing if not superstitious. Although Beatty isn’t one to take part in maritime myths, millennia-old habits die hard.

“I try not to be too superstitious,” he says. “But I’ve been wearing an anklet since I was a little kid. It’s super basic, just this rubber O-ring. If I ever service the engine on some significant vessel I’m working on, I take the O-ring out of the fuel filter and wear it until it breaks. I had one that lasted about 13 years.”

Perhaps it’s an inescapable trait that comes with the job, or a way to feel connected with the vessel that provides your livelihood and keeps you alive through unpredictable, hostile conditions. What’s for certain is that this is a way of life for him, and he wouldn’t have it any other way.

“I’ve always identified as a waterman,” Beatty says. “A waterman can live anywhere as long as there’s water present to make a living.”

Mr Michael Javidi can relate. The 43-year-old shipwright, furniture designer and multidisciplinary craftsman “grew up in Smithtown, so I was always by the water.” His studio is based in the seaport village of Greenport on Long Island’s North Fork, tucked away in an old barrel factory that’s surrounded by rolling farmland, vineyards and salty air.

He had made his way back home after closing the chapter on a previous career as a chef that bounced him around Colorado, Boston and Vancouver. He attended the North Bennet Street School’s furniture-making programme and quickly pivoted to life as a shipwright.

“It really expanded my skill set,” Javidi says. “Building wooden sailboats is a tricky business. These things are supposed to last hundreds of years, and you’re putting them in salt water. Not a good combo, but it actually works.”

“What drew me to boats is that they’re the perfect blend of function and form,” he says. “With traditional furniture making, a lot of it is over-embellished just to over-embellish it. Boats look beautiful because they have to be this shape to optimise the whole design. So, I brought that to my furniture, trying to pull this whole balance of function and form.”

These days, Javidi is venturing into uncharted waters. “I’ve done woodworking for so long,” he says. “What interests me now is learning new things. I’m doing a lot of bronze work, some sculptural stuff. Less splinters, more burns.”

No matter where their paths take them, there will always be an inescapable undercurrent that draws these men back to the shores they love the most. Given the enviable scenery, the sunsets, the sea breeze, and the occasional yacht club gala, it doesn’t sound like anyone is complaining.

“It’s definitely a curse I’m going to be living with for the rest of my life,” Meirowitz says with a laugh. “I grew up going to the beach every single day with my dad. He’s still an ocean lifeguard who just finished his 54th season. That was my childhood and probably what shaped me the most in my life. I will always be tied to the ocean.”