THE JOURNAL

Octopus being cooked at Morito, London. Photograph by Ms Issy Croker

Six exotic dishes for gastronomic explorers – including the ocean’s deadliest catch.

As the last under-explored frontier, the sea plays hosts to all manner of weird and wonderful creatures. To some, they’re species to study; to others, they’re better examined with a knife and fork. From the dawn of time, people have been using the ocean’s natural larder to great effect, experimenting by trial and error. Although with some underwater creatures, it’s a fine line between palate-pleasing delicacy and imminent death. We’ve rounded up six of the rarest sea creatures you can find on menus across the globe that are as ugly as they are delicious. Strap on your bib, request that finger bowl and head out into a brave new world of adventurous eating.

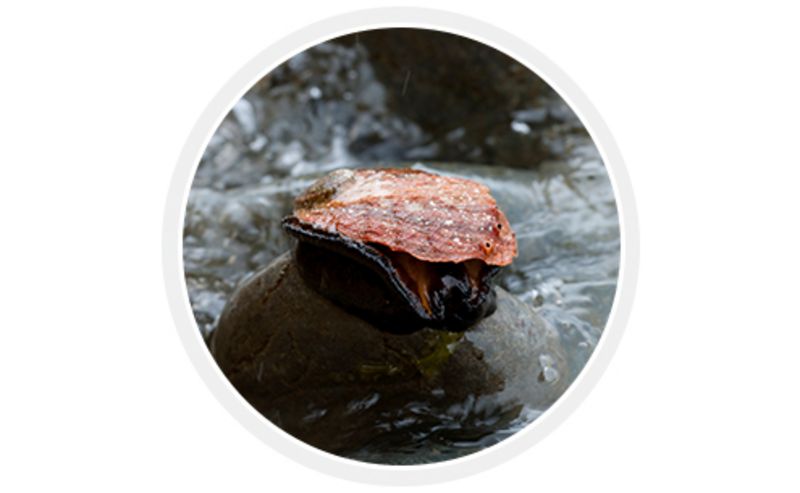

Awabi (raw abalone)

Awabi at Waku Ghin, Singapore. Photograph by City Foodsters. Below: photograph by Mr Markus Kirchgessner/Camera Press

Slower than molasses and certainly not as sweet, awabi is a large sea snail, which is generally served raw. Don’t be put off by its fleshy appearance; not only is it a delicacy that’s priced higher than gold in China and Japan, it’s only available in its fresh state between May and June, so it is as rare as it is low on aesthetic appeal. But its flavour is without question. Known as the “king of clams”, the edible part is actually its propulsion muscle, which is served sliced with the knife going against the grain to improve its texture. They take around three years to reach maturity, attaining the size of a bowling ball, and due to their popularity, have recently had fishing restrictions imposed. While farming is just starting to be implemented to maintain a healthy population, they’re shipped in from South Africa, Chile, Iceland, and Mexico to feed the East’s appetite.

Where to eat it: Sushi Sakai, Hakata, Japan The pared-back, stylish room in the business district of Hakata serves awabi on sushi rice, lightly battered and deep fried. Order it with a light kelp salad laced in Chinese chilli vinegar.

Ikizukuri (live sashimi)

Live shrimp (botanebi) and ants from the Nagano forests, Noma, Tokyo. Photograph by Mr Satoshi Nagare. Below: photograph by Mr Sven Paustian/Plainpicture

If you insist on going omakase (where the chef decides what you eat) in a Japanese restaurant, be warned. You could be confronted with ikizukuri – seafood (usually a prawn) that is “prepared alive” (literal translation). But if you like your dinner so fresh it still has a pulse, this variant on sushi is the one for you. Chefs must use no more, and no fewer, than three cuts to carve the fish. When presented, it is generally remodelled onto its still-warm body, twitching, and served on a bed of ice. Avoid eye contact as you dig in, but with a dash of wasabi and soy, it’s actually quite delicious. Firmer than sashimi and with a more sea-like flavour that’s closer to an oyster, it’s an eating experience you (or the sea creature) will never forget.

Where to eat it: Noma, on tour The two-time best restaurant in the world, Noma, has its HQ in Copenhagen, but has been on tour for the past 18 months, opening an outpost in Sydney and more recently, Japan. It serves a live langoustine on a bed of ice that’s best eaten with a smear of wasabi and soy.

Goose barnacles (percebes)

Percebes at Restaurante Casa do Pescador, Portugal. Photograph by Ms Gail Aguiar. Below: photograph by Mr Xavier Fores and Ms Joana Roncero/Alamy

Utterly delicious, but don’t be put off by a look which resembles the toothy, tentacle-like creatures from Mr Kevin Bacon B-movie Tremors. The shell of this mollusc can be found clinging to battered rock faces in Galicia and northern Portugal’s Atlantic coast, making their harvest a dangerous business, and giving the delicacy a hefty price tag. If they’re low in stock, restaurants will call their favourite patrons when they’ve received a shipment . That said, if you find yourself on the northern Spanish and Portuguese coast between August and November, asking a waiter will do no harm at all. If nothing else, it will mark you out as a man of good taste and distinction.

Where to eat it: Restaurante Casa do Pescador, Vilamoura, Portugal Set just off the marina, this restaurant is one of the bastions of quality Portuguese cuisine. They’re served boiled and then lightly fried to be dipped in aioli.

Fugu (puffer fish)

Fugu at Ajiman, Tokyo. Photograph by City Foodsters. Below: photograph by Mr David Fleetham/Alamy

Without a doubt the world’s deadliest catch. Eating the wrong part of the puffer fish can kill you in less than 24 hours. Its liver contains the poison tetrodotoxin, a substance 1,200 times more deadly than cyanide, but when prepared properly has the texture of silk and a delicate, almost citrus flavour unlike any other raw fish. You’d hope so, too, when next on the menu could be a painful asphyxiation-based death from which there’s no antidote. Sushi chefs need a licence to prepare it, which can take up to three years to obtain. The knife used to cut it even has a bespoke name – fugu-hiki – and it stays locked in a box until a customer orders the dish. You’ll probably remember the puffer from its contribution to The Simpsons canon, where Homer believes he’s eaten the deadly part that will kill him in 22 hours.

Where to eat it: Ajiman, Tokyo, Japan Considered by many as the best place in the world to eat the finest wild shiro tora-fugu.

Uni (sea urchin)

Uni at Alma, Los Angeles. Photograph by Ms Nastassia Clucas. Below: photograph by Angelica Linnhoff/StockFood

The bane of troglodytes from Maine to the Mediterranean, sea urchins have made a living out of depositing spines in beach combers’ feet for millennia. For about as long, they’ve been considered one of the true delicacies of the sea. In Japan, it’s available in a number of forms: fresh (nama uni), frozen (reito uni), baked then frozen (yaki uni), steamed (mushi uni), and salted (shio uni), but in and around the Mediterranean, where their availability varies depending on the time of year and tides, their gooey insides make for a fantastic pasta sauce with a beautiful mustard-hue. In Chile and across South America, they’re ceviched, with a lime juice, chilli and red-onion marinade. FYI, it is the gonads, or roe, that are the edible part.

Where to eat it: Alma, Los Angeles, US After being named Bon Appétit’s New Restaurant of the Year in 2013, Alma has gone from strength to strength. It serves boundary-pushing dishes like its guacamole topped with sea urchin that gives just the right amount of umami kick to the avocado.

Octopus

Grilled octopus and fava purée at Morito, London. Photograph by Ms Issy Croker. Below: photograph by Mr Martin Strmiska/Alamy

Rare in terms of it being nigh-on impossible to find it cooked well, octopus is eaten all over the world in myriad forms. Due to its size and abundance on certain coastlines, it’s a meat that can serve large numbers at a low price. In Europe, it’s commonly boiled to tenderise and served with the Mediterranean staples of garlic and olive oil; in Japan, it’s battered and served as crispy balls; in the Maldives, it’s cooked into a coconut curry; although in Korea, it gets really interesting. Served live at the table, in thin slivers sliced to be eaten while still squirming – and believed to increase a gentleman’s vitality. (Remember that bit in 2003’s Oldboy?) Adventurous? You bet. Inhumane. Certainly. We’ll stick to more traditional methods, thanks.

Where to eat it: Morito, London, UK The new Morito in London’s East End serves excellent Mediterranean-trotting small plates. Its octopus is boiled and served dusted with smoked paprika and caper berries with garlic-crushed potatoes. Delicious.