THE JOURNAL

The Royal Marines All Arms Commando Course is a 13-week programme of endurance exercises that culminates in a 30-mile, eight-hour fully laden trek across Dartmoor. Renowned the world over, it’s part of the selection process for the Royal Marines but is open to servicemen and women looking to work with the Marines in any capacity. Half of all participants fail to complete the course.

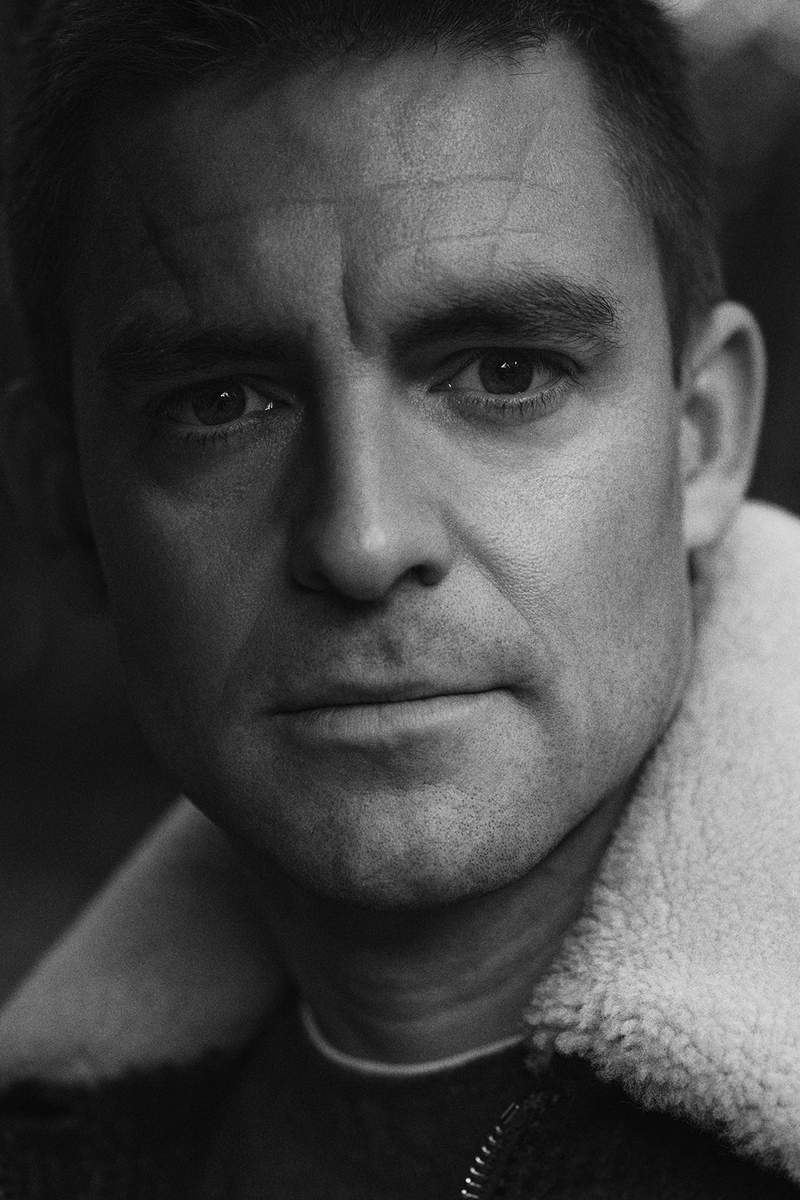

Last autumn, Lieutenant Commander Pete Reed, then 38, was taking part in the course when something felt wrong. On the morning of 3 September, after an assault course in weighted kit, he started to feel pain. “It was wrapped around my chest like a belt,” he says. “A bit like a rib stress fracture. My legs were no longer my own. They were weak, wobbly and I couldn’t feel where they were. I couldn’t walk it off, or pee, and went to bed that night hopeful but scared.”

At 6.00am the next morning, Mr Reed swung his legs out of his bunk and they gave way beneath him. By 9.00am, he was on his way to hospital in Plymouth, where doctors rushed him into MRI and CT scans before delivering the bad news: it looked like a spinal stroke, a disruption to the blood flow of the spinal column.

He was moved to an acute stroke ward and began days of tests, scans, lumbar punctures and medication. On the night of 6 September, the man in the next bed passed away. The next morning, Mr Reed walked into the waiting room and “saw the tear-soaked tissues and empty cups of tea… I took a photo to remind me of how lucky I was”. It was the last time he would stand; within a couple of hours, intense pain had returned to his torso and Mr Reed felt the life drain from his legs as he lay in bed. He was paralysed from halfway down his torso.

Raised in Gloucestershire, Mr Reed joined the Royal Navy aged 18. Despite standing 6ft 6in, he never warmed to sports at school; it was on a training exercise in the Persian Gulf that he discovered rowing, posting such a good time in his first 1,000m on a machine that the captain sought him out to recommend rowing at university.

It was a significant intervention – Mr Reed went on to be a member of Oxford University’s winning team in the 2004 Boat Race and was selected for Team GB the following year, embarking on a 27-race unbeaten run at international level as part of the coxless four. “I wanted to see if we could get to the middle of the podium [at Beijing]”, he says. “So, my coach wrote to the Admiralty to say, ‘Pete’s got potential’.” The Navy agreed, giving him three years to train, compete and then return to service after the 2008 Olympic Games.

To cut a glittering story short, gold in Beijing led to gold in London in 2012, and then another gold in Rio in 2016. A three-year career break had turned into 13 (Mr Reed finally hung up his oars in 2018), during which time he had become one of the nation’s most decorated Olympians and a five-time world champion. It had been a groundbreaking journey, laying the template for the Royal Navy’s elite sport programme. But the desire to return to the career he had signed up for on his 18th birthday was stronger than ever.

The plan was to work with both the Navy and Royal Marines, imparting some of what he had learnt as an elite athlete. You don’t have to spend long with Mr Reed to understand that giving back is more important to him than personal achievement. Talk turns frequently to his “values”, and he speaks more eloquently about notions of duty, integrity and public service than any politician.

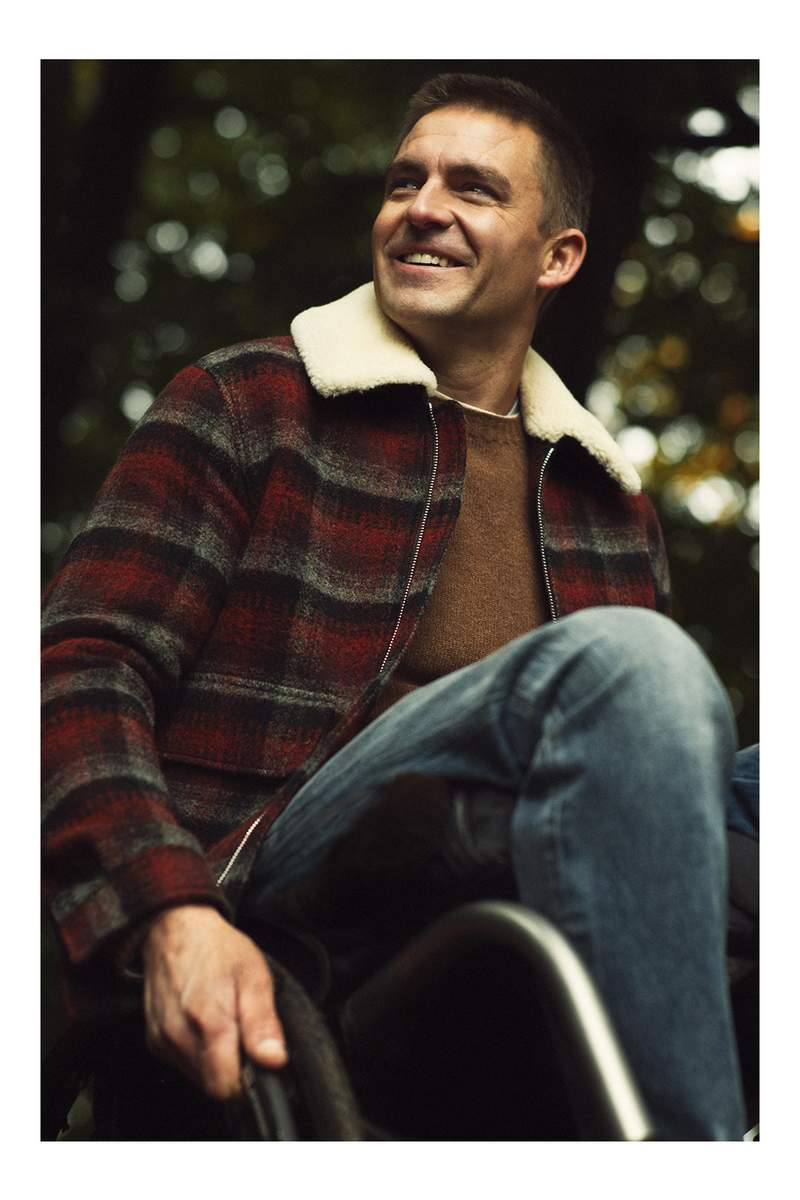

Since posting news of his spinal stroke in a video, Mr Reed has documented his life on Instagram, sharing the highs and lows of his road to recovery, facing adversity with his head held high. Although his mindset is a product of his unique career, the optimism and advice he shares online are relatable for us all, and they represent genuine inspiration on a platform dominated by glossy, manufactured emotion. In a year that has delivered bad news to so many, it’s powerful, perspective-giving stuff.

“The general public don’t have access to disability,” says Mr Reed. “I was completely ignorant of all sorts of things that my eyes are open to now.” He sees his social media presence as a responsibility to educate people, but admits he considered never making his injury public at all. “I’ve got a funny relationship with social media, and I never craved fame,” he admits. “I don’t need to be in the public eye, I’m a public servant.” He insists he would rather people were outside getting some exercise than scrolling through his feed.

“When I could do things, I did do things. I climbed mountains when I could, I travelled when I could, I pushed my body to its limits”

Remarkably, Mr Reed is able to not only approach rehab with a positive mentality, but call out ways in which his life has actually improved. “My old life is over. But [his partner] Jeannie and I are stronger than ever; I’ve got a better relationship with my friends than ever. I feel like more of a three-dimensional person now, and I understand more about other people’s traumas. I’ve got more empathy for others.”

The doctors now believe that Mr Reed’s spinal stroke was a result of something called a fibrocartilaginous embolism, a rare blockage of an artery within the spinal column that can occur after a minor injury, a fall or over-extension of the spine. “It’s most likely to have been because of the [Royal Marines] course,” he says. “But it will only be proven with an autopsy, so we can wait for that.”

It seems a bitter irony that he should suffer such an injury while pushing himself back into serving his country, but nothing in Mr Reed’s psyche could countenance shying away from a challenge. “I was proving something to myself; it probably didn’t need to be done, but I have no regrets. Even knowing that I’m in a wheelchair now, I’d still go back and do it again, because at least I tried. I get wonderful reassurance that when I could do things, I did do things. I climbed mountains when I could, I travelled when I could, I pushed my body to its limits.”

A recurring theme is to look forward, not back, and if he never truly knows what happened, it won’t matter to him. “Bad things happen, and life isn’t fair. And it’s hard, but spending too much time dwelling on that is poison.”

In the early days, Mr Reed says he couldn’t entertain the idea of long-term rehab: “I’ve never been [seriously] injured before, so I assumed I’d be in hospital, get fixed, walk back out again and go for a jog. Because that’s what I do.”

But what is the outlook today?

“When I moved to Salisbury spinal unit, the consultant came to see me on my first day. He just dropped into the flow of conversation the fact I wouldn’t walk again and then just carried on with other stuff. I was like, ‘Hang on a second.’”

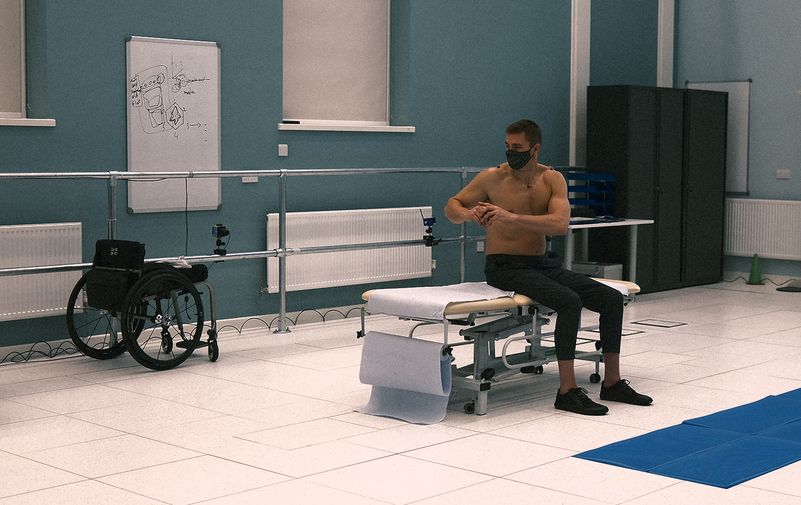

Typically, the first two years after such an injury are when most gains are made; Mr Reed has made steady progress, but it may not be enough. The structure of his Olympic training has provided a framework, mentally speaking, for him to draw on, but it is a framework built on ever-shifting foundations.

“My whole adult life, I’ve been an athlete, and our routine was to set a goal four years in advance: an Olympic gold medal,” he says. “We’d know the place, the time, the date, the standard and what we needed to do to get there. And now what we’ve got is the equivalent of a fourth Olympic gold medal: walking again. But as the weeks and months go on, I’m having to reel in what my expectations are. Because if I don’t, then at some point, I’m going to get a nasty shock. Now the aim, by the end of rehab, is to be able to stand, which is more likely.

“I think people see you in a wheelchair and think, ‘Oh, that’s hard, he can’t walk’. There are lots of other things that are worse. Can I go to the toilet by myself? Will I be able to pee again? Can Jeannie and I have a family? All these things are much more important than walking.”

“As soon as I got on the bus and people moved for me, I really had to face up to the realisation that, ‘Shit, I’m vulnerable now’”

Along with the physical hardships, the stroke brought home the realisation that his size and strength were more than just attributes, they defined his place in society. “I’m at the bottom of the pecking order. I’ve gone from the top one per cent of physical capability to probably the bottom one per cent and it’s not going away overnight,” he says, matter-of-fact.

He remains steadfastly upbeat about life in a wheelchair, but everyday encounters, such as an elderly lady giving up space for him on the bus, can hit hard. “That was the first time that I had to publicly acknowledge my vulnerability,” he says. “I never looked in the mirror in hospital. And even when I was outside, everything looks the same to me and I forget that I look different. So, as soon as I got on the bus and people moved for me, I really had to face up to the realisation that, ‘Shit, I’m vulnerable now’. That was tough.”

Spending even a little time with him is enough to get a glimpse into his new reality. The muscle around his backside has wasted away, so he carries an inflatable seat cushion for when he transfers into a regular chair. He has gone up a shoe size (from 12 to 13 thanks to water retention). Hoisting his leg up to show me the sole of his foot, he laughs that he will never wear out a pair of shoes again.

He must manage his diet meticulously because his body won’t break down food in his intestines as it used to. His ability to burn calories through exercise is restricted by only having roughly a third of his muscle mass available.

Everything takes longer to do – getting dressed, getting washed, getting in and out of the car (he drives a hand-controlled Audi). And despite his indefatigable attitude, there is no amount of positive thinking that will overcome a doorway that’s too narrow, as he found last Christmas in an Airbnb with Jeannie’s family.

“The door to the loo was about 5mm too narrow for my wheelchair,” he says. “So, I can see the toilet and the reality is I’m going to have to undo my fly and catheterise myself – a medical procedure – in the kitchen while everyone else is trying not to look, and then give the bag to Jeannie to take to the toilet. Part of going through these traumas is having to handle those situations with a light heart.”

Lieutenant Commander Pete Reed at the Defence Medical Rehabilitation Centre, Stanford Hall, October 2020. Photograph courtesy of Lieutenant Commander Pete Reed

It is not lost on Mr Reed or those closest to him that if you were going to live your life in preparation for exactly this injury, you would lead the life he has since he left school.

“There really might not be anyone better equipped to deal with this. I mean, maybe anyone,” he says, with no trace of a boast. “I’m not God’s gift to anything at all, but the things that make my spinal cord injury life easier are the things that made me a good rower. My entire adult life has been controlled. I wasn’t the best at everything in sport, but I was particularly good at self-discipline, and it gave me an edge. Boring as hell, but it has seen me through this chapter.”

What the next chapter holds is anyone’s guess. Uncertainty hovers over the most basic elements – where to live once out of rehab, what work will look like. His eloquent Instagram posts and public profile would make him an effective campaigner.

“I’ve definitely got a voice,” he agrees. “I think about all the disabled people who feel like they are getting drowned out, who lack the reach or access that I have.”

The door isn’t closed on his ambition to give something back to the forces, but for now, rehab must come first. “We’re probably a year away from getting that next step sorted,” he says. “And the reason why we’re a year away is that if I’m not putting every single effort into walking again, then I’ll have real regret.”