THE JOURNAL

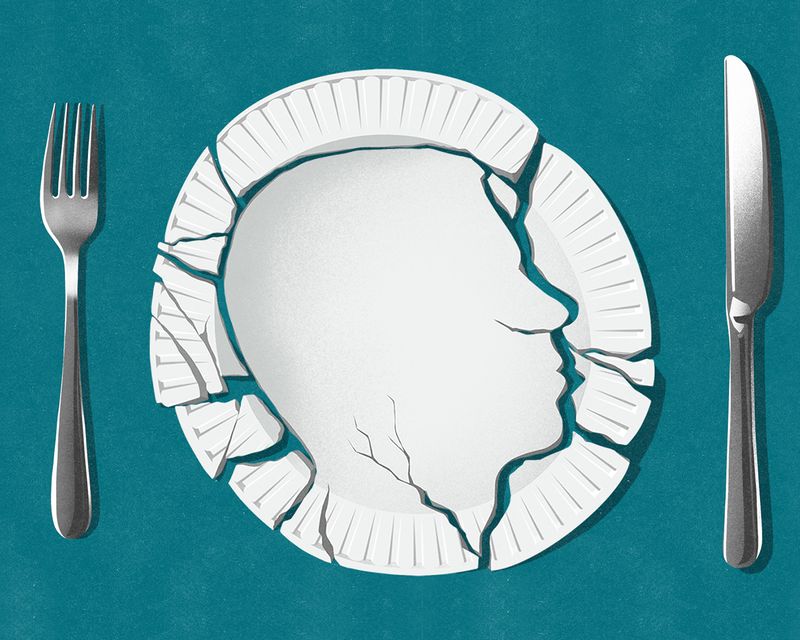

“I Can Teach A Yoga Class, Eat For Two Hours And Be Sick” – The Alarming Rise Of Eating Disorders In Men

Mr James Downs avoided main roads on the walk to his high school because, in his mind, he was so ugly that any car driver who saw him would crash. He studied his appearance in every reflective surface he passed for so much as a solitary out-of-place hair. Eventually he couldn’t bring himself to enter school, so he’d walk around Cardiff all day and lie to his parents. Nearly a year went by before anybody noticed.

From a young age, Downs had exhibited “little signs” of a budding body consciousness – not wanting to take his top off or go swimming – that was exacerbated by early puberty and a difficult transition to high school. He was bullied for being bright, playing the violin, having long hair, wearing glasses. He started taking longer, hours, to get ready in the morning, to perform his washing rituals. “I had to have this sense of safety that came from my body being as acceptable as possible,” he says. Perhaps because he still did well academically, the school wasn’t that bothered by his absences and assumed he was bunking off out of arrogance.

When it all came out after an end-of-year parents’ evening, Downs went to his GP, then mental health services. Aged 14, he was diagnosed with obsessive compulsive disorder, body dysmorphia (classified among “obsessive-compulsive and related” disorders), depression and anxiety. Because he was bright, the professionals assumed he’d “get” the cognitive behavioural therapy that they prescribed and told him to stop his washing rituals and take down his mirrors. While from the outside he seemed to be doing well, inside he felt more depressed, even suicidal. “I thought, ‘How can I communicate this to them?’” he says. “There was a shift from my appearance generally, my hair and skin, to weight and shape.” Soon, as he began to dramatically lose weight, it became clear he wasn’t doing well from the outside.

At 15, he was diagnosed with anorexia. From the Greek “without appetite”, anorexia is an eating disorder typically characterised by low weight due to limiting food and drink intake and has the highest mortality rate of all mental illnesses – even higher for men, who are less likely than women to seek treatment or be diagnosed early, partly because of the assumption that eating disorders are “women’s issues” (people thought Downs had cancer).

It’s believed a quarter of the estimated 1.25m people in the UK with an eating disorder could be male, although conclusive research is lacking and stigma may stop more sufferers from coming forward. What is known is that more men are being treated for eating disorders, whether that reflects increasing prevalence or recognition. From 2007-8 to 2019-20, NHS figures for males admitted to hospital with an eating disorder quadrupled.

“Anorexia has the highest mortality rate of all mental illnesses – even higher for men, who are less likely than women to seek treatment or be diagnosed early”

Downs didn’t have the energy to educate his school, which was unsupportive, so he found it easier not to go, which made him more isolated. He was sent to an intensive treatment team, which didn’t specialise or have much training in eating disorders. Heavily medicated, he was repeatedly threatened that if he didn’t eat he’d be detained in hospital for his own safety. Once, after he hadn’t drunk for a few days, he was taken to hospital. Verging on a coma, a doctor told him he could be kept alive when unconscious, but maybe not for ever.

“I felt like, ‘Nobody is going to step in, I can keep going, keep starving myself, keep losing weight and my heart will stop,’” says Downs. “And there was something really alienating about that.” Yet the realisation was also empowering: “It reinforced to me, a little too much, ‘You’re on your own.’”

Downs started eating more – to the point where, because of his loss of appetite regulation and his body’s drive to replenish its stores in preparation for future famines, he was sick. The transition he made around 18 from anorexia to bulimia, typically characterised by a cycle of bingeing on huge quantities of food followed by compensatory purging (by vomiting, fasting, over-exercising or taking laxatives or diuretics), is common – the two conditions overlap – but was missed by his team because they weren’t eating disorder specialists. He voiced his concern that he was overeating, but was told that was his anorexia talking, so he didn’t mention it again. “I didn’t bother telling the GP because I didn’t want them to ignore it as well,’” he says. “And so I just decided to go it alone.”

It took seven years before Downs received specialist eating disorder treatment. Studying medicine at Bristol, but spending more time as a patient, bingeing and purging 12 hours a day, increasingly depressed at the prospect of having to drop out and go back to Wales, he confided that he was feeling suicidal to his GP, who told him that eating disorders were just attention-seeking. Weren’t they? “I felt very numb,” says Downs. “And then that night I tried to kill myself.”

Downs had tried to overdose before, but this one had intent. In a moment of doubt, he called the Samaritans and paramedics knocked down his door. He woke up in hospital where, unlike previously when all the attention had been on the physical symptoms, he was seen by a crisis team and diagnosed with a personality disorder. After a four-month referral process, he was eventually seen by a service for “high risk” eating disorders and was immediately hospitalised.

Downs underwent a year of dialectical behaviour therapy, a form of CBT for intense emotions that reconciles seemingly opposing ideas – like accepting difficult feelings and also managing them, or accepting yourself and also changing your behaviour – after which he was considered no longer high risk. He wasn’t “recovered”, but he could start to build a life. He completed a degree, then a masters, and is currently studying for a doctorate in counselling psychology. And he took up yoga, which he now teaches. But he continues to live with the disorder. “People can’t understand that I can go home after teaching a yoga class, eat for two hours and be sick,” he says.

Now 32, Downs is particularly vulnerable in the evenings, when his ADHD medication wears off and he’s alone, craving stimulus. (Eating disorders often co-occur with other mental health problems; anorexia in particular is associated with traits such as cognitive rigidity and perfectionism that are common with OCD, while body image concerns are widespread across eating disorders.) He has tried to build his life up “until it outweighs the eating disorder”, and his other coping mechanisms to be more rehearsed and effective. But he remains in a physiological trap that’s habitual, “almost comforting”. And he’s been set back by the pandemic, which triggered what one expert called a “tsunami” of eating disorder patients with its perfect storm of anxiety, isolation, restricted access to food and inescapable messages about diet, weight and physical activity. In lockdown, Downs couldn’t eat in public with other people to minimise secrecy and shame, or shop little and often to avert bingeing.

“Our ways of understanding, diagnosing and treating eating disorders are limited and outdated. This needs to change so that all patients with eating disorders, including men like us, receive the care that we need”

Downs’ story is his own, but he believes other men need eating disorder treatment that considers their shared, “distinctive” experience as men. He co-authored an opinion piece published earlier this month in the British Medical Journal arguing that, while there’s no “single, unified experience”, or “one-size-fits-all” eating disorder, male patients are “too often failed” by fixed ideas of who eating disorders affect and how. Cultural veneration of male muscularity can make it hard for men, and the healthcare professionals they consult, to realise there’s a problem: a GP once praised Downs, seeking help for compulsive exercise, for looking “toned”. We need to broaden societal understanding of the range of eating difficulties that can affect anyone, write Downs and co-author Mr George Mycock (founder of mental health organisation MyoMinds for athletes and exercisers), and increase training on them for healthcare professionals: UK medical undergraduates currently get less than two hours.

“Our ways of understanding, diagnosing and treating eating disorders are limited and outdated,” the co-authors conclude. “This needs to change so that all patients with eating disorders, including men like us, receive the care that we need.”

It’s important, says Downs, not to get caught up in the “injustice” of the system, as he has at points, and to understand that not getting specialist support, or having to wait, or not finding it helpful isn’t a reflection on your worth or the seriousness of your problems. If you are seeking help, be as honest as you can and forearm yourself with information. He recommends the charity Beat Eating Disorders’ guide for going to the GP: “Because the professionals might not have specialist training, and it’s not that they don’t want to help you – they’re doing the best they can with what they have.”

If you can afford it then therapy not specific to eating disorders, whether in person or via one of the online services that have proliferated post-Covid, can still help, says Downs. He believes that the isolation of an eating disorder must also be addressed outside therapy, in life. Beat has a guide for family and friends, who often want to help but don’t know how. Whether from eating disorder or general mental health support groups, or other forms of community, social support “can’t be underestimated”, says Downs, who tries to do “things that are therapeutic” for him, such as yoga, and give them value. Ask yourself: what do you want your life to be like?

We need to get better, says Downs, at helping people with eating disorders to break their cyclical behaviours but not just remove them without providing another coping mechanism: “But we can only see what is going on if people can talk about it, and if we’re open to what they’re saying, and what their experience is, as being unique for them.”