THE JOURNAL

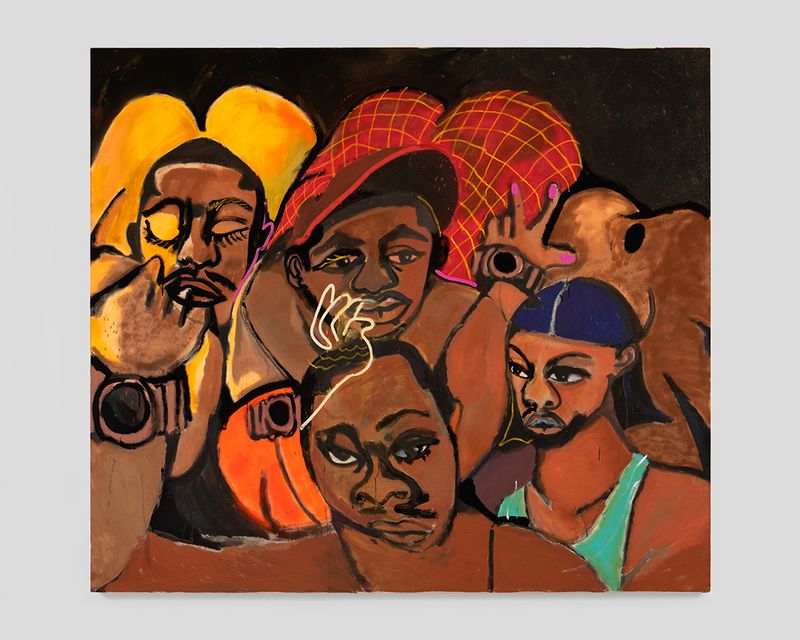

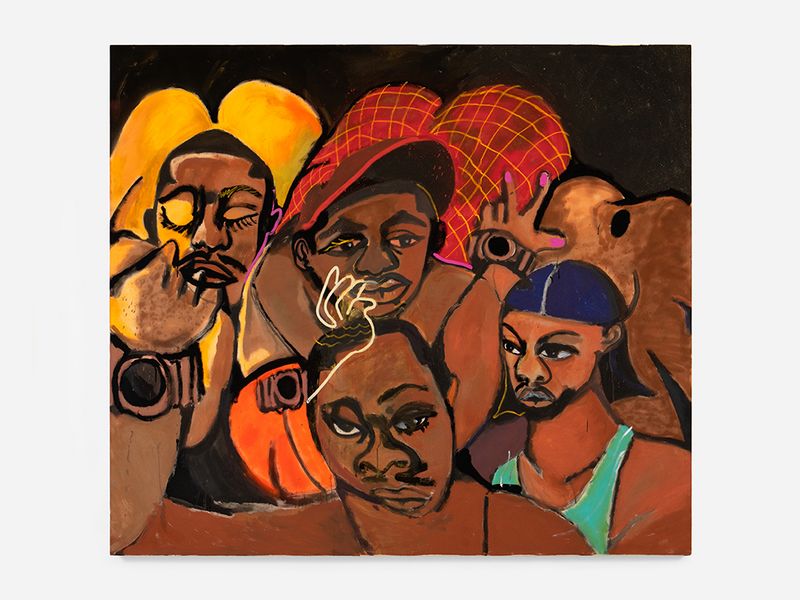

Mx Jonathan Lyndon Chase, “The SleepOver”, 2022. Photograph by Ms Katie Morrison. © Jonathan Lyndon Chase. Courtesy of the Artist and Sadie Coles HQ, London

Artists have long painted poetic images of blown-out candles, stacked skulls, or open books, to illustrate our fleeting time on Earth. Then about a century ago, a cultural shift occurred at about the time when watches transitioned from a luxury item reserved for a wealthy elite to a common tool accessible to many. Once a feminine accessory designed to allow women to discreetly to check the time without offending male company, wristwatches evolved into a mostly masculine status symbol. Suddenly, humble time-measuring instruments piqued the curiosity of previously disinterested artists.

In the 1960s, a milestone at the intersection of art and horology was reached when Mr Pablo Picasso first inscribed his name on a watch dial used as a canvas. Since then, watches have continued to creep into our collective psyche as era-defining objects worthy of artistic representation and rich with symbolism. In time, they have come to represent everything from modern-day memento mori and thought-provoking symbols of consumerism and technological obsolescence, to signifiers of taste and social status.

There are many brilliant examples of modern and contemporary artists depicting watches in their work. The following demonstrate how in the skillful hands of an artist, a utilitarian tool can become a vessel for communicating subtle and complex commentary on man’s very place in the world.

01. Mr Salvador Dalí

The Persistence of Memory, 1931

Mr Salvador Dalí, “The Persistence of Memory”, 1931. Photograph by The Museum of Modern Art, New York/Scala, Florence 2023. © Salvador Dali, Fundació

Mr Salvador Dalí painted “The Persistence of Memory,” depicting melting pocket watches in a desolate landscape on a canvas barely bigger than an A4-size paper. The painting has since become monumental in the Spanish artist’s surrealist repertoire. By painting melting watches, Dalí set out to make ordinary objects into extraordinary creations, in a meticulously realistic style that underscored the strangeness of his hallucinatory composition.

In creating this work, Dalí was inspired by a piece of soft cheese in his kitchen. “The camembert of time,” he said, symbolised time in movement, where past, present and future lost their conventional meaning by coexisting on the same plane.

His floppy watches became symbols of an alternative reality, in various states of decay – softly melting or swarmed by ants – representing different temporalities that make our perception of time, object of Dalí’s fascination, meaningless.

02. Mr Francis Bacon

Study for Self-Portrait, 1973

Mr Francis Bacon, “Study for Self-Portrait”, 1973. Photograph by Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd 2023. © The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved

The Irish-born artist, Mr Francis Bacon, was known to wear his shirt sleeves rolled up, to show off both his shapely forearms and his Rolex GMT Master.

Mortality became a recurring theme in Bacon’s work, especially after the suicide of his partner, Mr George Dyer, in 1971. In innumerable self-portraits painted after that date, including “Study for Self-Portrait” in 1973, Bacon portrayed himself with a ravaged expression, a wristwatch painted by his face. “I loathe my own face,” he said. “I’ve done a lot of self-portraits, really because people have been dying around me like flies and I’ve nobody else left to paint but myself.”

The ticking watch serves as a reminder of the passage of time, a modern-day vanitas that captures the artist’s existentialist angst on the irreversible march to death.

03. Mr Richard Prince

Untitled (hand with cigarette and watch), 1980

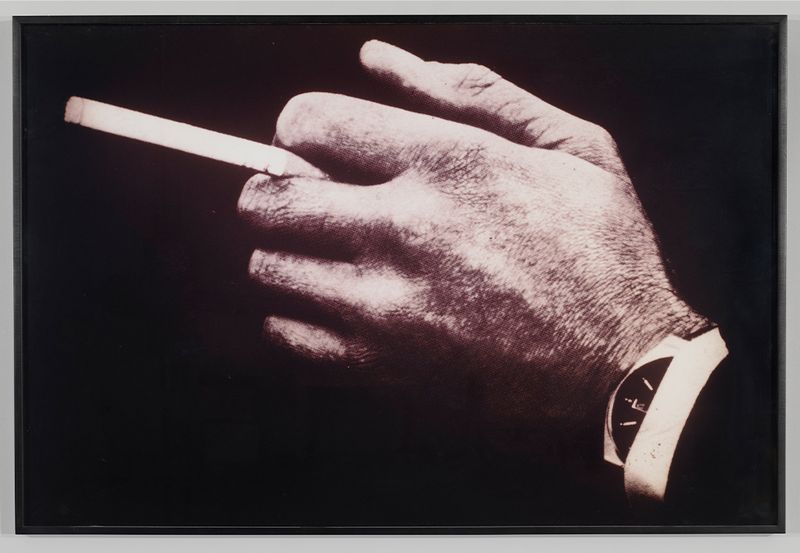

Mr Richard Prince, “Untitled (hand with cigarette and watch)”, 1980. Photograph Whitney Museum of Art/Scala, Florence 2023. © Richard Prince

Mr Richard Prince has devoted much of his career to photographing the work of others, a provocative practice known as artistic appropriation that involves re-photographing existing images taken from magazines or advertisements as his own artwork while challenging conventional notions of authorship and authenticity.

In “Untitled (hand with cigarette and watch)” Prince appropriates an advertising image of a disembodied male hand holding a cigarette, a sleek watch visible under the cuff of a dress shirt. “I must have taken a hundred pictures of watches, but never wore one,” the artist said. “The way they were presented in say, the magazines, looking like living things. That’s what I liked. They look like they had egos.”

Devoid of its brand name and advertising slogan, the watch becomes a classical vanity object, an accoutrement of a clichéd virility and an object of a manufactured desire, forcing the viewer to acknowledge the intent and effect of the advertisement.

04. Mr Michael Craig-Martin

Wristwatch, 1986

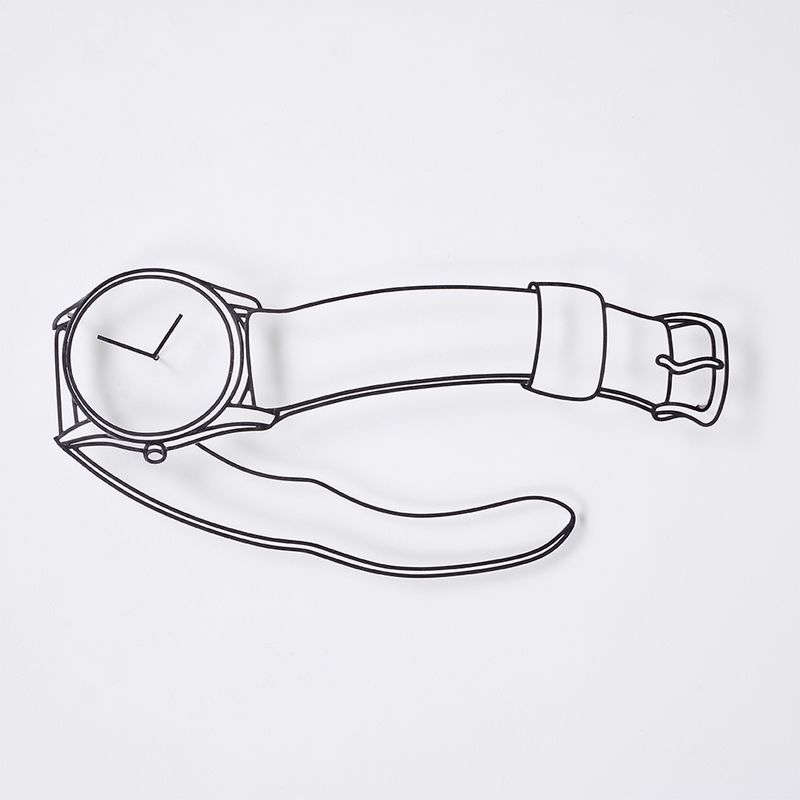

Mr Michael Craig-Martin, “Wristwatch”, 1986. Photograph courtesy of Phillips. ©Michael Craig-Martin

The Dublin-born conceptual artist, Mr Michael Craig-Martin, started making line drawings of ordinary objects in the 1970s. “Wristwatch” created in 1986 is both a still-life and a universal portrait that seeks to capture the essence of a watch, which the artist describes as “an object of our of time, without a context, not relational, no shadow, no ageing.”

“I wanted to make drawings that were as neutral as the objects,” Craig-Martin explained. “These are mass produced objects that are perfect and bland in a way that they are fabricated. I tried to make the drawing precise, with a line has no inflection, in a drawing that has no style at all.”

The artist’s deliberately minimalist style helps to create a universal representation of the watch, in a simple composition that removes any subjective view from the perception of the object. The neutral quality of the drawing touches with subtlety on consumerism. It also suggests a form of spirituality in industrial design that co-exists in the shadow of a looming obsolescence.

05. Mr Philip Guston

Agean, 1978

Mr Philip Guston, “Agean”, 1978. Photograph by Ms Genevieve Hanson. © The Estate of Philip Guston, courtesy Hauser & Wirth

Mr Philip Guston, a Canadian-born, US-raised artist, started out as an Abstract Expressionist painter who shocked the art world when in 1970, he turned to a “cartoonish” style of figurative painting. Mixing elements of the tragic with a dry humour, his work belongs to the tradition of political caricature associated with the French painter, Mr Honoré Daumier, and the English painter and satirist, Mr William Hogarth.

In “Agean”, an enigmatic tangle of hairy outstretched disembodied arms – one wearing a watch – and paws thrust at each other with trash can shields. The work is a cartoonish reprise of an earlier work titled “Gladiators” (1940), in depicting hooded boys fighting on a city sidewalk with swords and trash can lids, a social commentary on racial urban violence.

Using a palette of pink, red and grey, Guston expresses a stance on politics, art and society with images in which watches are often depicted at the end of an extended arm, or as clocks painted with one or no hands, and impart a sense of dread and time running out.

06. Mx Jonathan Lyndon Chase

The SleepOver, 2022

Mx Jonathan Lyndon Chase, “The SleepOver”, 2022. Photograph by Ms Katie Morrison. © Jonathan Lyndon Chase. Courtesy of the Artist and Sadie Coles HQ, London

A rising star of the art market, the Philadelphia-based multidisciplinary artist Mx Jonathan Lyndon Chase tackles issues of race, gender and sexuality through their own experience being Black and queer in contemporary America.

Lyndon Chase often depicts men wearing conspicuous wristwatches, as in “The SleepOver”, where in a group of four Black men, three are wearing large ostentatious timepieces. The watch is a social signifier that the artist defines as a “tool of gay male non-verbal communication,” and also an everyday object that brings a touch of the familiar in paintings described as “queertopia” of intermingled bodies.

“Time plays an important role in my work because I am always thinking about how bodies wade through time and autopilot ourselves through spaces” Lyndon Chase says. “Is time linear, is it more like a web, or is it solely a construct of human invention?” the artist asks, touching on universal themes that continue to fascinate artists and their audience.