THE JOURNAL

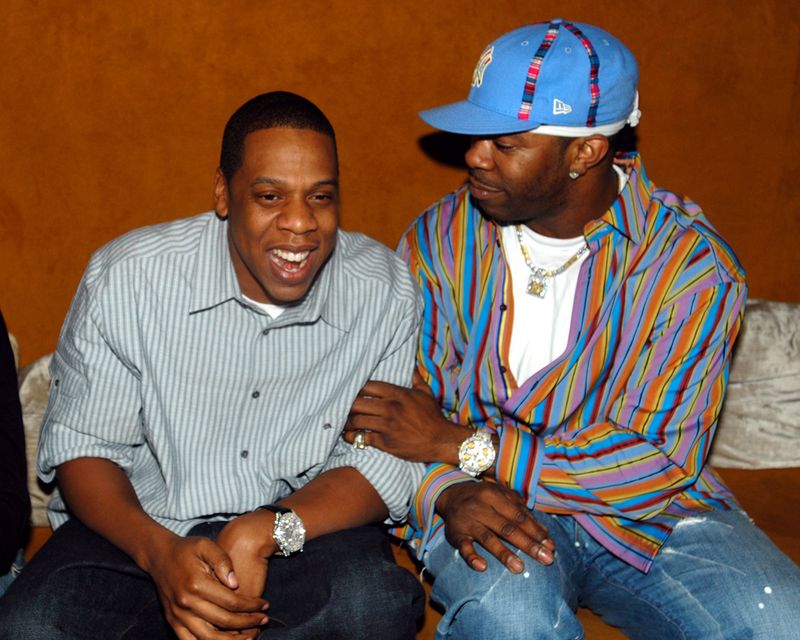

Jay-Z and Busta Rhymes at The 40/40 Club, New York, 9 February 2005. Photograph by Ms Carley Margolis/Getty Images

Diamonds. Stones associated with love, romance, Ms Marilyn Monroe. Their cold, hard beauty has been prized by royalty, both Hollywood and hereditary, as a sign of wealth and status. And although diamonds and women have been inextricably linked, recent red-carpet appearances by Mr Harry Styles and Mr Timothée Chalamet and Mr Brooklyn Peltz Beckham’s dazzler of a wedding band are all signs that diamonds are no longer just a girl’s best friend.

In the world of watches, there is no doubt at all. The most macho megastars – be it Jay-Z, Drake, Mr Anthony Joshua or Mr Cristiano Ronaldo – are spending their millions on fully iced-out designs. It’s nothing new, however, and it cannot be simply dismissed as tasteless bling, as it might have been a decade ago. It is true that today’s superstars can trace their taste in watches back to the birth of hip-hop in the 1980s, but the full story of diamond-set watches – for men, in particular – is longer and more complex.

We have the Victorians to blame for the gendering of gemstones. “It’s virtually impossible to say whether a watch made between 1500 and 1800 was designed for a man or a woman without additional provenance,” says Ms Rebecca Struthers, master watchmaker and horological historian. “The Victorians were the first to define gender in life and fashion quite rigidly. It was the era of the tailored suit and gentlemen’s clubs. The lives of men and women became increasingly segregated. Men’s and women’s roles become more defined, with men being the strong, fearless, outdoorsy ones and women being small, quiet and pretty, staying at home doing needlepoint. Fashions evolved to suit those gender norms.”

Victorian-era pocket watches soon gave way to early wristwatches, which had a functional genesis, forged as they were in the trenches of WWI. The thought of adding diamonds would have been anathema to all concerned. It was another war that changed things – WWII.

In the 1940s and early 1950s, the US didn’t suffer the post-war ravages to its economy that affected Europe. In the boom years that followed WWII, diamond-set designs for men flourished. It wasn’t just about demonstrating their new-found prosperity, either. Some men sought out diamond-set watches as a celebration of having survived such a traumatic experience. However, high import taxes on finished watches from Switzerland meant that known Swiss names opened subsidiaries in the US to cater for local demand. The movements would come from Switzerland, but the casing and gem-setting were done to local tastes.

Longines was then known for creating diamond-set styles for men, particularly its Mystery watches, which were designed with the tastes of the US gentleman in mind, his European counterpart apparently favouring all-gold bracelet designs as a signifier of wealth. Jaeger-LeCoultre, operating in the US as LeCoultre, worked in partnership with Vacheron Constantin to create diamond-set mystery styles, the latter bolstering the former’s ailing finances in a US economy where a sector of society was eager for ways to demonstrate its wealth. Even Hamilton, a brand now renowned for rugged tool watches, was catering to this new desire for diamonds.

Eventually, in the 1950s, following the war in Korea, recession hit the US, but that didn’t stop Swiss brands dabbling in diamonds. They started doing it for the domestic market. Briefly, Patek Philippe and Audemars Piguet flirted with diamonds as a decorative option for a limited selection of models.

“The general population didn’t know names then, but if you’re flashing stones around, there is no question you have money”

“It’s very different from what people would think of now,” says Mr Alex Barter, author of The Watch: A Twentieth-Century Style History. “It would have been a bit of gentle flash, not bling. And diamond-set numerals would have been practical on a dress watch, allowing you to read the time.”

Barter believes factors such as the 1973 oil crisis, various recessions and the rise of the quartz watch meant diamonds disappeared from men’s designs. In the 1960s, there was a preference for a more pared-back aesthetic. Then the 1980s arrived and opulence, as well as greed, was good. “The general population didn’t know names then, but if you’re flashing stones around, there is no question you have money,” says Barter. And no one knew how to flash stones like the rising stars of hip-hop.

Entertainers such as Messrs Sammy Davis Jr and Elvis Presley continued to fly the diamond-set flag, but gem-setting disappeared from men’s wrists until hip-hop brought it back – in a way that made a little Rat Pack glimmer look positively puritan. Although there is anecdotal evidence that The Sugarhill Gang were the first to start wearing expensive watches on stage, the best visual touchpoint for the birth of diamond watches in hip-hop is the 1987 Melody Maker cover, shot by Ms Janette Beckman, that features LL Cool J and his full pavé Gruen. It was a sign of the trend for diamond-set men’s watches that was forged in New York where the hip-hop scene was thriving and a young Uzbek immigrant, Mr Jacob Arabo, had just set up shop.

To many people now, the name Mr Jacob Arabo, if you know it at all, is synonymous with ostentatious, mechanically complex timepieces produced under the auspices of his Swiss watch brand, Jacob & Co. But to rappers such as LL Cool J, Jay-Z and Nas, he is known as Jacob the Jeweller (a moniker bestowed, supposedly, by The Notorious BIG) or simply, the Bling King.

Arabo’s career started in New York’s diamond district where, age 16, after enrolling on a six-month jewellery course sponsored by the Hassidic Jewish community, he lied about his age to secure a $125-a-week job welding gold bracelets while developing his own designs on the side. By the age of 17, he had opened his own factory and by the early 1990s he had caught the attention of The Notorious BIG, LL Cool J, Mr Sean Combs, aka Puff Daddy aka Love, Nas and Jay-Z.

“In the 1980s and 1990s, I saw what people were doing and what the demand was for, so I started developing something that nobody has ever done before,” says Arabo. “Bling-bling didn’t exist before me. The size and quality were of the utmost importance. This was something new to the industry.”

At first Arabo was fulfilling demand for diamond jewellery, but then these stars started asking him to ice their timepieces as well. One of the most outlandish creations, a watch that epitomises the culture, is a Rolex that Arabo worked on for Slick Rick, the English-American 1980s rapper and producer who was introduced to Arabo through Def Jam, the record label to which he was signed at the time. This watch is unrecognisable as a modest Rolex Day-Date given that the dial is surrounded by no fewer than five concentric circular plates, fully studded with diamonds, each added one at a time to create a watch that’s the size of a drinks coaster.

“Slick Rick wanted an oversized piece,” says Arabo casually, as if sticking that number of stones around a dial is an everyday occurrence. “Nobody had ever done anything like that before. It was a challenge to develop, but you have to take risks, and this is what I did.”

This wasn’t just ostentation for the sake of it. “The reason rappers wanted these big new iced-out pieces is because it brought the most attention to them when they were on stage. The shine, the sparkle – this was a sign of success in the industry.” That impulse hasn’t changed since the 1990s, but these days it is not just hip-hop stars who want diamonds on their watches.

“Hip-hop culture is about unabashedly displaying the fruits of your labour,” says Mr Mo Jooma, owner of Icebox, the Atlanta store where the modern generation of hip-hop stars go to buy their jewellery and have their watches “buss down”, or fully pavé-set in jewellery parlance.

“And today, hip-hop sets the tone for pop culture altogether. So now you’re seeing, across the board, athletes, actors, business owners, entrepreneurs, anyone who has achieved some level of success wanting to overtly represent it. More and more, we’re seeing these symbolic displays of wealth and success and hip-hop music is the conduit. Diamonds are visually stunning. They are captivating to behold and they are a great store of value. Diamonds have always been a signifier of luxury and hip-hop recognised that. And because hip-hop recognises it, today the rest of the world recognises it, too.”

“Diamonds have always been a signifier of luxury and hip-hop recognised that. And because hip-hop recognises it, the rest of the world recognises it, too”

This is something with which Mr Chiefer Appiah, London-born jeweller and self-proclaimed Bussdown King, who creates pieces for the boxer Mr Anthony Joshua and rappers Abra Cadabra and Dutchavelli, agrees. He also locates this desire among hip-hop and rap artists to customise their watches in the need for self-expression.

“Within the past 20 years no one would have touched a watch because it would have reduced its value,” he says. “Last seven or eight, that changed because of the constant struggle for identity. Everyone wants to be unique. Buy a Rolex and you’ll see 10 of them walking down the street. This trend was set up by a hip-hop culture dying to be different.”

Appiah has also noticed the same trickle-down effect, but he’s seeing it in the brands themselves. “Fully pavé wasn’t done, which was why we did it,” he says. “Now all the new watches are the same as the ones we were criticised for doing. And the whole method, the stones touching shoulder to shoulder, they never used to do that before and now in the window of Patek, there’s bussdowns. We do dictate and lead this luxury culture.”

There is also a subversive, political side to the bussdown. It can be argued that by diamond-setting their Rolexes and Audemars Piguets, these stars were claiming their own space in a world that wasn’t for them, a world dominated by rich, white men for whom modifying a watch was just not the done thing.

In the 1980s, Dapper Dan in Harlem took the logos of the luxury fashion houses that refused to allow him to stock them, screen printed them onto premium leathers and transformed them into the hip-hop uniform of the day before becoming the darling of the very brands that snubbed him. It’s possible to argue that the same has happened with diamond setting on men’s watches. First, it’s a counter-cultural statement, then, over time, the world’s luxury brands start to cater for the sector they were eschewing. The watch industry has now well and truly caught up.

“It’s not just affluent people wearing these things,” says Appiah. “The brands need to embrace people like me, collaborate with us and get it right with the history and the knowledge. It’s how Virgil [Abloh] could walk into Louis Vuitton. There’s a new freedom with watches and jewellery and these brands need to embrace that. I have the highest respect for these brands, 100 per cent. They’ve been doing this for hundreds of years, but there’s up and coming new talent out there and they need to collaborate with it. And if they need some pointers on how to do a proper bussdown, we can help.”