THE JOURNAL

Joshua Tree National Park, California, US. Photograph by Mr Lars Schneider/Tandemstock.com

For years, I shunned national parks. I refused to pay an entry fee, wait in line, listen to a ranger tell me the rules, or dodge some fogey blocking the road with his Winnebago as he snapped photos of a moose. I was a wilderness snob, and when I went outdoors, I bumped down miles of dirt road, hauled a pack over passes and across rivers, all in search of solitude.

I missed a lot. The parks are parks because they hold the wonders of the continent. And in a time when other public lands feel overrun by the Xtra Xtreme gnarliness, rope-swingers, bungee-jumpers and mountain bike-rampagers, there’s something comforting about the twilight haze of pine smoke over a campground, the sturdy, engraved wooden trail signs, the late-night murmur of flasks passed around a fire, and the early-morning tooth brushing with strangers – a sense of belonging to a tribe who think that there is no purpose higher in going into nature than sitting around and walking around.

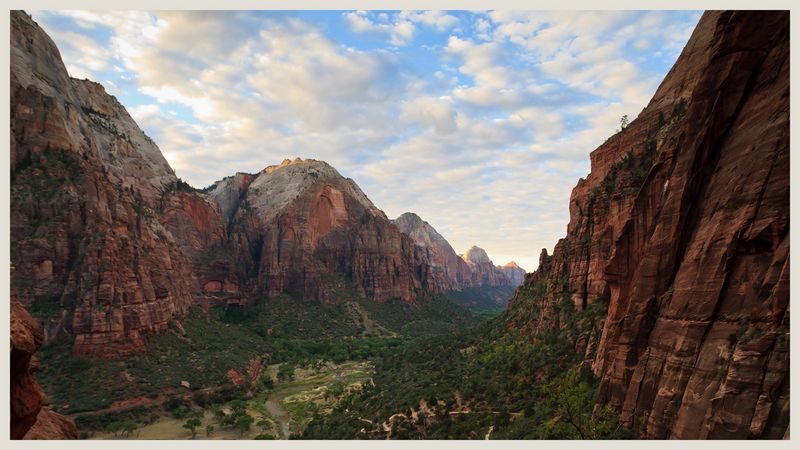

Virgin, Utah

Zion, South Campground

Photograph by Ms Eleanor Scriven/Mr Robert Harding

What with the tightly packed sites, the standing-room-only shuttle buses, and easily accessible breweries and cafés just outside the gate, this ain’t wilderness. What it is, frankly, is European. It’s crowded here, but not with the chubby land-yachtsmen gawking at squirrels. It draws a salad of international travellers, big blonde Mormon families and hip multi-lingual Californian college kids, all bedecked with Camelbaks and trekking poles and neoprene boots, breaking camp at dawn for the classic arduous hikes of The Narrows and Angels Landing. With Zion Canyon mercifully closed to cars most of the year, there’s no “drive-through” tourism here, and the only way to see the place is on your own two feet.

North Rim, Arizona

Grand Canyon, North Rim Campground

Photograph by Mr James Kaiser jameskaiser.com

Anyone who has ever shaken his sweating fist at a summer traffic jam on the Canyon’s South Rim and vowed to never return should make the long drive to the opposite cliff, where the North Rim feels stuck in a 1950s time warp, complete with a log-cabin general store that sells single beers and cups of coffee, and a mid-century showerhouse where you plug in six quarters for five minutes. The site rests in the deep shade of ponderosas, just a few minutes’ walk from the rim. Follow the trail for a mile along the cliffs and arrive at the stunning Grand Canyon Lodge, constructed in the 1920s of limestone slabs and pine timbers and – as far as I can tell – never updated. Thank God. It’s a cross between a ski chalet and a Bavarian fortress, and at sunset, it’s uncrowded enough to claim one of the Adirondack chairs on the stone veranda and order a Bud and a quesadilla and watch the pink canyon dissolve into darkness.

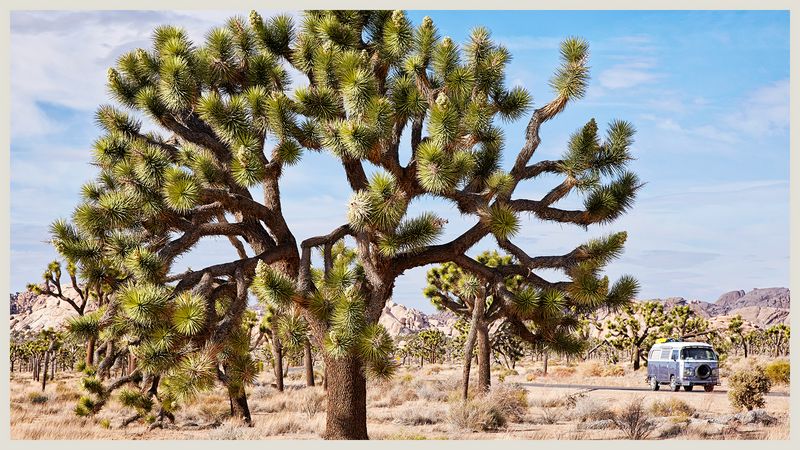

Twentynine Palms, California

Joshua Tree, Hidden Valley Campground

Photograph by Stan Moniz Photography/Tandemstock.com

I spent my teen years here, scampering dangerously to places called the Hobbit Hole and the Space Station and the Chasm of Doom. But I fear it has never fully recovered from the U2 album – the cover image for which wasn’t actually shot in the park, but 200 miles away at Zabriskie Point – after which every Hollywood sleezebag with an electric guitar and a ponytail spent a weekend here taking moody selfies with cacti. Yeah, man, it’s like, biblical. But still: the rocks. The light of campfires flickering across bulbous cliffs, the humanoid silhouettes of the Joshua trees, the splatter of stars across the black sky... There’s nowhere like it.

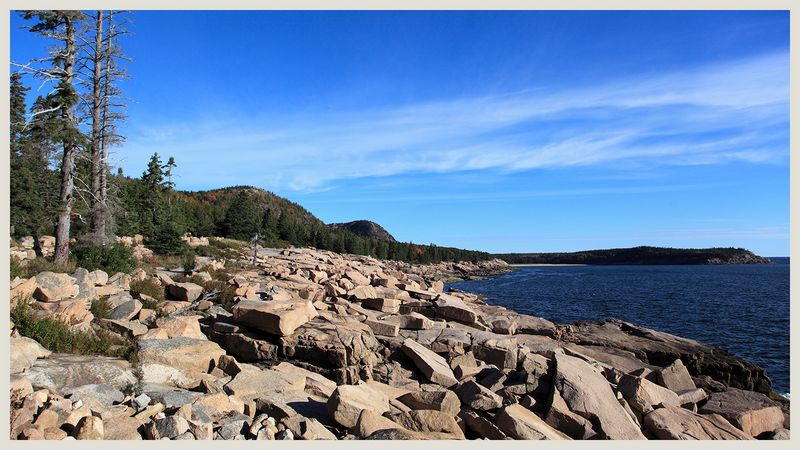

Southwest Harbor, Maine

Acadia, Seawall Campground

Photograph by Ms Wendy Connett/Mr Robert Harding

As a native Westerner, it’s hard for me to admit that the East Coast might be as handsome when it comes to the outdoors, but I wish that all campgrounds would imitate Seawall and kick out the cars. Most of the sites here are “walk-in”, meaning you park in a lot and haul your gear a couple of hundred yards into the woods. You’re still close to your neighbours, but the druidy result is a sort of Rainbow Gathering peacefulness, far from the beep-beeps of doors ajar and the ding-dongs of cell phones a-charge. Rent bikes and see most of this compact park from the saddle on paths once built for horse carriages where cars are still banned.

East Glacier Park, Montana

Glacier National Park, Two Medicine Campground

Photograph by Mr Jordan Siemens/Tandemstock.com

Tucked in a forest on the banks of Pray Lake, this spot affords summer travellers the rare thrill of plunging in glacial waters. Walk directly out of your tent to the 17-mile Pitamakin/Dawson loop hike, a park classic that combines lakeside huckleberry picking with a wind-scoured rock traverse high above tree line. You can shave a few miles off the trek – or opt out of it entirely – by catching a pleasure cruise across Two Medicine Lake in the creaky, charming, old wooden tour boat, the Sinopah.

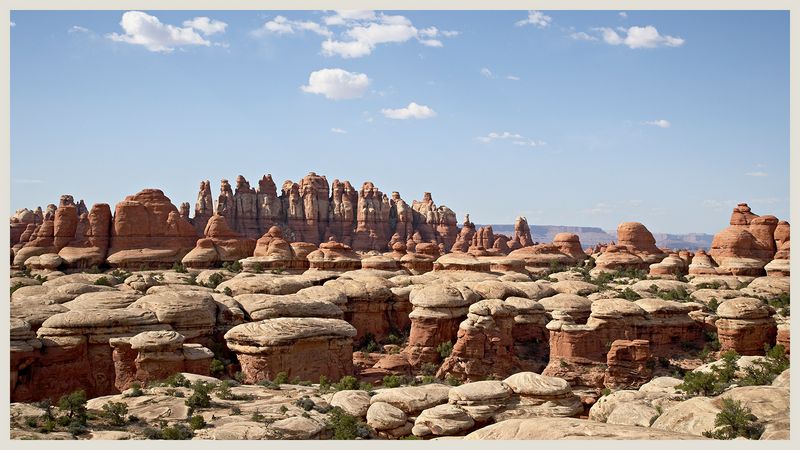

Moab, Utah

Canyonlands National Park, The Needles Campground

Photograph by Mr James Hager/Mr Robert Harding

While Moab has become the poster-child of public lands loved to death by the adoring masses, the Needles District just 90 minutes south remains a windblown outpost that accommodates just a handful of campers in its red rock outcroppings. There is no electricity, or showers, but plenty of sandstone and moonlight. You’re situated at the trailhead to Chesler Park, one of the great hikes in the west, which can be done in a long day or as part of a multiday backpack.

Yosemite Valley, California

Yosemite National Park, Tuolumne Meadows Campground

Photograph by Mr Justin Bailie/Tandemstock.com

As teenage rockclimbers from the LA suburbs, my friend and I were literally dropped off here by his mom and told to have fun for the week. I’ll never think of it without that thrill of independence and danger. While Yosemite Valley has become a hot stinking parking lot, the high-alpine Tuolumne Meadows still affords cool nights and uncrowded trails up to its many granite domes. The splendid camp at 8,600ft is only open in the summer, and is frequently full, but you can find ample Forest Service camps just outside the gate on the Tioga Pass road.

Before you go:

Plan ahead at recreation.gov. Reservations at these sites are comically difficult to secure, often filling up six months in advance. Most campgrounds hold a portion of sites for walk-ins, but ask ahead, and be prepared to queue up at the crack of dawn, with no guarantee.

Buy bulk. As entrance fees creep upward of $30, save time and hassles by getting an annual pass to all the parks for just $80.

Sorry, Spot. Dogs are not allowed on the hiking trails in national parks. Unless you like the thought of locking your pooch in the car all day, leave him at home.