THE JOURNAL

Photograph by Alinari/REX Shutterstock

The noms de plume of celebrated authors revealed.

Not long ago, there was an enchanting discovery made in literary academia. Mr Walt Whitman, founding father of American poetry, had written a long-forgotten newspaper advice column under the name Mr Mose Velsor, in which he gave his opinion on everything from the correct use of beards to the diets and exercise regimes his readers ought to follow. The whole lot has just been republished as Manly Health And Training.

If you’re a writer with an established reputation, why would you work under a different name? Sometimes curiosity, sometimes discretion, sometimes a change of genre, sometimes just the wish for a clean start. But you’d be surprised at how many of the biggest names in literature have, at one time or another, snuck out some work under some, well, smaller names in literature.

FOR A CHALLENGE

Mr Stephen King, among the most successful popular novelists of modern times, quietly started publishing novels as Mr Richard Bachman in the 1970s and 1980s. Mr King later said that he’d intended them, in part, to be a test. Had his success under his own name been a fluke? He published six novels as Mr Bachman, including Rage, The Long Walk, Thinner and The Running Man, before being “outed” by a fan who’d noticed similarities in the style, and discovered Mr King’s name on a Bachman copyright record in the Library of Congress. Mr King went on to write (under his own name) The Dark Half, a novel about an author who is haunted by his own malevolent pseudonym.

TO CHANGE GENRE

The Man Booker Prize-winning literary novelist Mr John Banville – acclaimed for his Nabokovian prose – also publishes detective novels as Mr Benjamin Black. The pseudonym is more prolific. “Poor old Banville takes three, four, five years to write a book,” he lamented in an interview. “Black does it in three or four months.” Mr Banville/Black isn’t the only literary author who adopts a pseudonym for genre work. Mr Iain Banks wrote science fiction as Mr Iain M Banks. Ms Agatha Christie became Ms Mary Westmacott for her romance novels. Ms Ruth Rendell stayed in genre when she wrote as Ms Barbara Vine, but her Ms Vine crime novels were distinctly darker and grittier than the ones she penned under her real name.

JUST FOR FUN

Mr Julian Barnes, another Man Booker winner, wrote a series of comic crime novels as Mr Dan Kavanagh, the surname borrowed from his late wife, the literary agent Ms Pat Kavanagh. They featured a bisexual detective called Duffy, and Mr Dan Kavanagh’s author biography changed subtly according to the world in which each of the books was set (Putting The Boot In was football, Going To The Dogs greyhound racing, etc).

TO ALLEVIATE PRESSURE

Ms J K Rowling followed Mr Stephen King’s lead when in 2013 she published her first grown-up thriller, The Cuckoo’s Calling, as Mr Robert Galbraith. Where some pseudonyms are open secrets, Mr Galbraith’s real identity (he claimed to be a former plainclothes Royal Military Police investigator) was not. Still, despite her best efforts, Ms Rowling was outed within months. She said ruefully that, while it lasted, it had been “wonderful to publish without hype or expectation, and a pure pleasure to get feedback under a different name”.

TO INDULGE IN SMUT

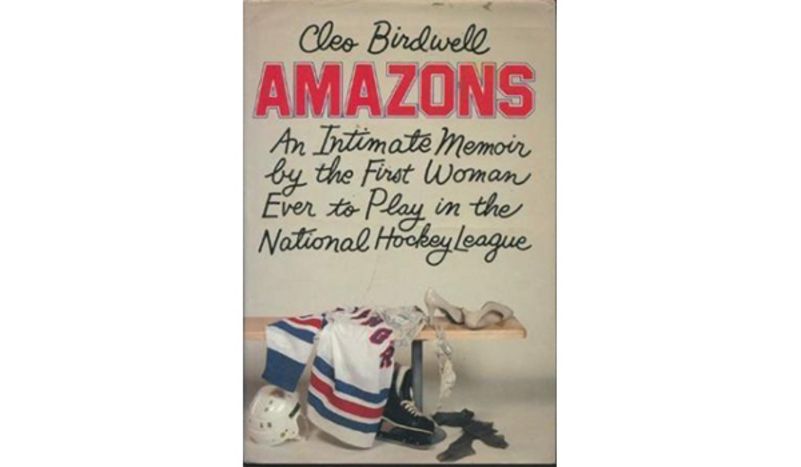

Good old-fashioned smut can also be a reason for the veil of pseudonymous discretion. Mr Christopher Logue, the distinguished poet and translator of Homer, used to knock out dirty books for Mr Maurice Girodias’s Olympia Press in Paris under the name Count Palmiro Vicarion. Likewise, not many people know that Ms Cleo Birdwell, the author of the distinctly racy 1980 book Amazons: An Intimate Memoir By The First Woman Ever To Play In The National Hockey League was, in fact, Mr Don DeLillo.