THE JOURNAL

Mr Stanley Kubrick on the set of 2001: A Space Odyssey. Photograph © Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc., courtesy of The Design Museum

While born and raised in New York, Mr Stanley Kubrick spent much of his life in the UK, producing the bulk of his films here. It’s perhaps surprising then that the official exhibition on the visionary director – which was first set up in Frankfurt 15 years ago and has since toured the world, taking in cities as far-flung as Melbourne, LA, São Paulo and, most recently, Barcelona – has taken until now to arrive in his adoptive homeland. In truth, it is only down to serendipity that the show has even made it this far (or near, given that it offers a rare airing for artefacts drawn from Mr Kubrick’s own meticulously kept archive in London). Indeed, in what could itself be an opening scene from a movie, it all stems from a chance meeting at a train station.

“We’d been thinking about bringing it to London for a long time, but it really only took off when I bumped into Alan [Yentob, former BBC creative director and a friend of Mr Kubrick] at St Pancras,” Mr Deyan Sudjic, co-director of the Design Museum, which will be housing Stanley Kubrick: The Exhibition until September. “He’d just been to see Jan Harlan, Kubrick’s brother-in-law, who’d worked on all of his films from A Clockwork Orange onwards. He just said, ‘You’ve got to do this show.’ And I said, ‘That’s a good idea.’

“The archive is pretty impressive,” says Mr Sudjic. “His documents, his scripts, his director’s chair. We’ve got the only Oscar he ever won. But we don’t want it to just be a show of posters and old costumes – we want to make it come alive.”

Alongside props, the exhibition promises clips from his films projected onto vast screens, fully immersing visitors into Mr Kubrick’s world vision. But it also presented the Design Museum with a unique opportunity to reconnect the director’s work with Britain itself. “We’re trying to make it have relevance to London, where he made almost all of his films. Even Lolita was filmed in the UK, and in a way that was what he was about. He actually created these very complete worlds, each one entirely different, he made Vietnam in Beckton; he made New York in Commercial Road for Eyes Wide Shut. He tried to recreate these extraordinary country houses for Barry Lyndon in the UK, so it’s a great story and a great thing to try and give life to.”

Here, Mr Sudjic selects three of his favourite items on display as part of the exhibition.

Djinn chair by Mr Olivier Mourgue from 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

Photograph © Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc., courtesy of The Design Museum

Found in 2001’s Space Station V – the transfer point to the Moon, seen orbiting the Earth to the sounds of Mr Johann Strauss II’s “Blue Danube Waltz” in the film – this 1965 design by Mr Olivier Mourgue for French manufacturer Airborne International instills “Kubrick’s art director’s take on what the future would look like”, says Mr Sudjic. “They are amazing pieces of free-form design that would look pretty startling in your living room now, never mind what it was like in 1966 when he found them.”

This particular item is unlikely to be the actual chair Mr Leonard Rossiter – “wearing his Russian scientist outfit designed by Hardy Amies” – sat on in the film. “Most of the stuff that came from the shoot was dumped afterwards, sadly,” says Mr Sudjic.

“The thing about Kubrick is that he has hardcore followers who explore every shot for nuances, so there’s a bit of an argument about what the actual colour of the Djinn chair was – was it pink or orange? Ours is pink.”

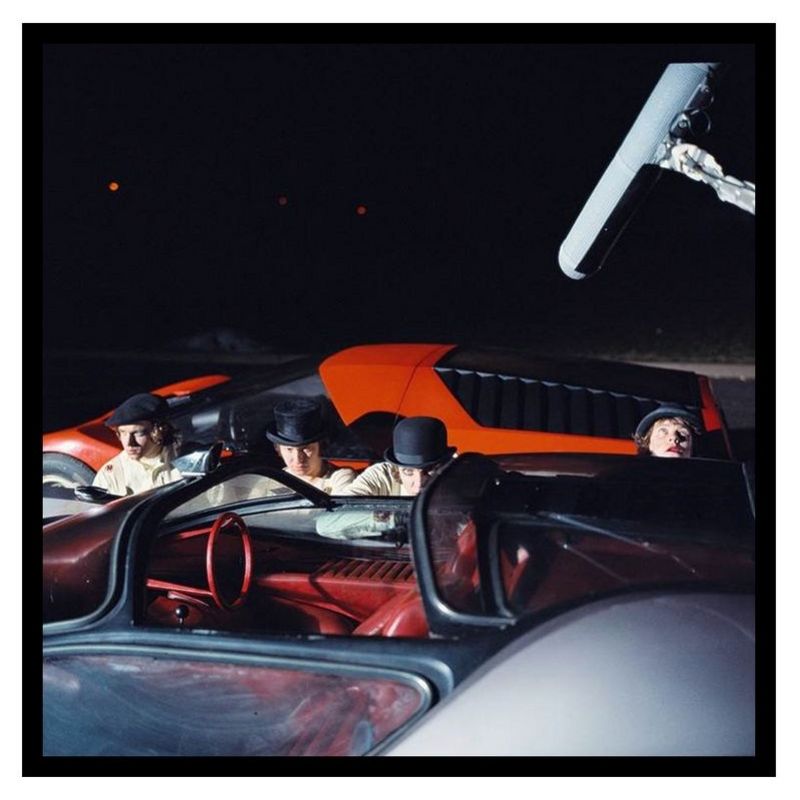

Probe 16 car by Adams Brothers from A Clockwork Orange (1971)

Alex and his Droogs hiding behind the Probe 16 car. On the set of A Clockwork Orange, 1970-71. Photograph by The Stanley Kubrick Estate, courtesy of The Design Museum

Referred to as the “Durango 95”, the car driven by Alex (Mr Malcolm McDowell) in A Clockwork Orange was a real-life, roadworthy vehicle, built in 1969 by brothers Messrs Dennis and Peter Adams, former employees of now-defunct British sportscar marque Marcos.

“I was looking at the film again and I suddenly realised there was this car,” says Mr Sudjic. “I thought, ‘What is it?’ And we tracked it down. Only three were ever made – the one we have was used in the film, it’s been restored since then. We had Malcolm McDowell in the museum last week and he confirmed that it was the car he’d been in.”

Made as “an investigation into extremes of styling” at the brothers’ facility in Bradford-on-Avon, Wiltshire, at its tallest point the Probe 16 stands just 86cm off the ground.

“It’s very, very low,” says Mr Sudjic. “You’d need more of a periscope than a rearview mirror. There are no doors as such, it’s an open top. You have to get into it by limbo dancing.”

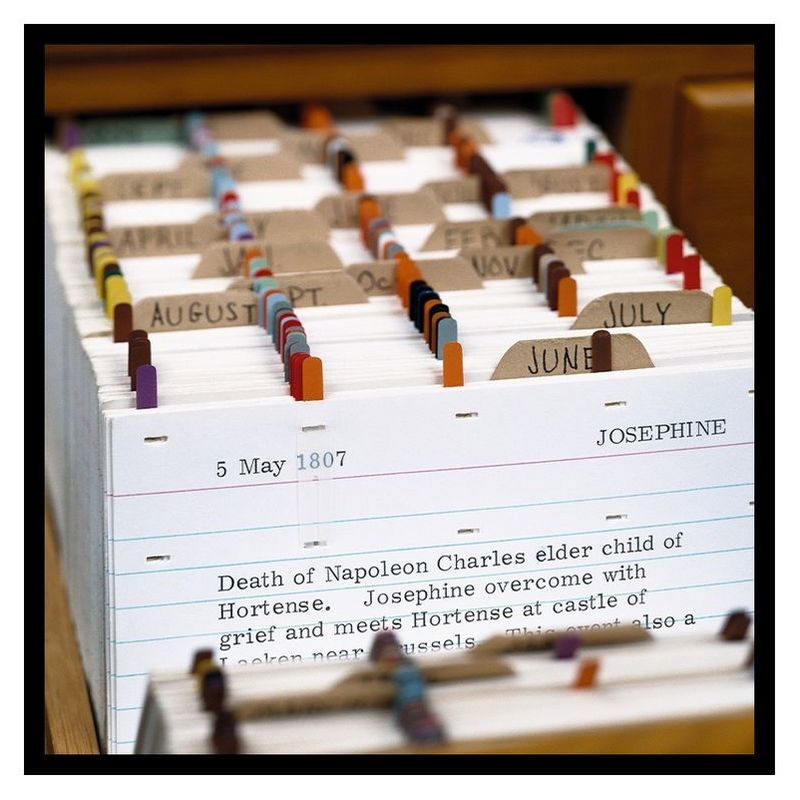

Mr Kubrick’s Emperor Napoleon card index from an unfilmed project

Mr Stanley Kubrick’s Napoleon file card cabinet. Photograph by The Stanley Kubrick Estate, courtesy of The Design Museum

“What’s interesting about Kubrick is the films that he never managed to make are almost as important as the ones he did make,” says Mr Sudjic. “One of which was AI, which he actually gave as a project to Spielberg. But what he really spent a lot of energy on was Napoleon, which he described as the greatest story it’s ever possible to tell.”

Following 2001, Mr Kubrick set about the suitably Napoleonic task of filming the life story of the French emperor and general. A script exists, and 50,000 Romanian soldiers were reportedly enlisted to star, but mounting costs and the 1966 release of Mr Sergei Bondarchuk’s adaptation of War And Peace led to production being wound down.

“He tried to cast Audrey Hepburn as Josephine, but she turned it down,” says Mr Sudjic. “And there was talk of Jack Nicholson as Napoleon. But like all his films, he started out with a great deal of research. He hired researchers to tour Europe and he built up this card index, which I describe as a kind of analogue Wikipedia. He wanted to know every day of Napoleon’s life: what did he have for breakfast? Who did he see? What was going on?”

Mr Kubrick’s filing cabinet is rumoured to contain 25,000 cards. “I haven’t counted them, but there’s a lot. Plus, all the books. We’ve also got drawings, which show work on the costumes – there’s an amazing amount of material. Here is this thing that meant so much to Kubrick, which never actually led to a project, although now, apparently, Spielberg is trying to film it as a series for Netflix.”