THE JOURNAL

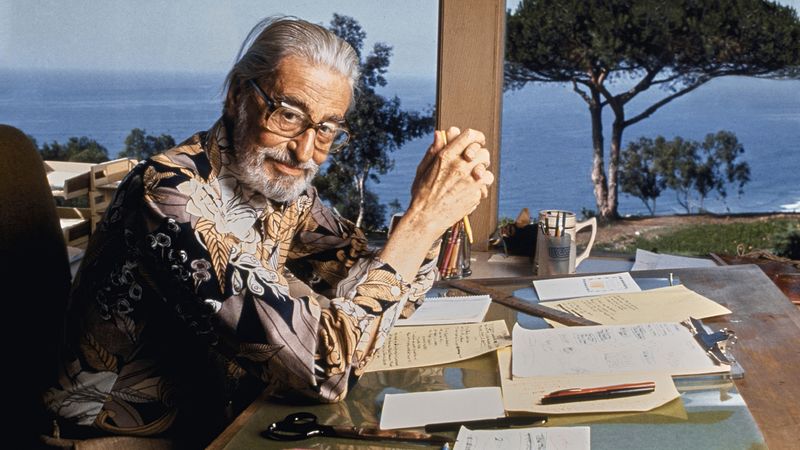

Mr Theodor Geisel at home, California, February 1984. Photograph by Mr Mark Kauffman/The LIFE Images Collection via Getty Images.

“It’s a shirt. It’s a sock. It’s a glove. It’s a hat,” writes Mr Theodor Seuss Geisel in The Lorax, his game-changing children’s book, first published 50 years ago today_. _“But it has other uses. Yes, far beyond that. You can use it for carpets. For pillows! For sheets! Or curtains! Or covers for bicycle seats!” The item Geisel – far better known by his pen name, Dr Seuss – is describing is a Thneed, a covetable, versatile item as any stocked by MR PORTER. But even if a Thneed was a real-world product rather than one plucked from Dr Seuss’ boundless imagination, it’s still too good to be true. For while there’s much that this “fine-something-that-all-people-need” is, what it isn’t is sustainable.

Clothing is a theme that runs through the doctrines of Dr Seuss. From The Cat In The Hat and Fox In Socks to the Grinch and the Santa suit he pulls on to fool the Whos, the author’s characters are often defined by what they wear. But The Lorax is by far his deepest dive into the world of fashion; specifically the destructive tendencies of fast fashion, or any industry with a growth model that exceeds the natural resources available to it for that matter.

Half a century on, though, just as production methods have fallen under increased scrutiny, so too has the work of Dr Seuss himself. Earlier this year, the estate of Dr Seuss announced that it would cease the publication of six of his other titles that “portray people in ways that are hurtful and wrong” as “part of our commitment and our broader plan to ensure [Dr Seuss’] catalogue represents and supports all communities and families”.

“Dr Seuss was a latecomer to progressive causes,” says Dr Donald E Pease, professor of English and comparative literature at Dartmouth College (which counts Geisel himself among its alumni) and author of a 2010 Dr Seuss biography.

No matter how problematic the author becomes, it would be a shame to lose The Lorax. According to Dr Pease, it was Dr Seuss’ favourite of his own books. “He also described it as the hardest thing he’d ever done,” Dr Pease says. “Geisel had often warned fellow children’s book writers against becoming propagandists, ‘more interested in messages than story’. The Lorax was unlike other Dr Seuss books in that its storyline conveyed an overarching political message.”

The story itself begins at the end, in a ravaged wasteland, decimated by the greed of a creature called the Once-ler, who still lives at the far end of town. Here, the reader, depicted as a curious boy in a stripy sweater, comes to discover the fate of the legendary Lorax.

“Way back in the days when the grass was still green and the pond was still wet and the clouds were still clean,” the Once-ler tells the boy, describing the world that once was. “I came to this glorious place. And I first saw the trees! The Truffula Trees!”

“Softer than silk”, it is the tuft of the Truffula Tree that the Once-ler uses in the manufacture of his Thneeds. Only, to make a single Thneed means felling an entire Truffula Tree. And once the Once-ler ramps up production (a process he calls “biggering”), it’s not long before the whole forest is gone.

“The Lorax was his favourite book. He also described it as the hardest thing he’d ever done”

“It is a cautionary tale told almost completely from the perspective of the villain,” says actor, writer and director Mr Wes Tank, which, he notes, is “pretty rare for a children’s book”.

Tank, who presents on the streaming service Kidoodle.TV, last year made a series of YouTube videos that feature him rapping Dr Seuss lyrics over Dr Dre beats. Now officially endorsed by the estate of Dr Seuss (as well as Dr Dre – “I was informed that Dre loved the videos,” Tank says), his take on The Lorax is well worth 10 minutes of your time.

“Geisel invented the Thneed as an easily understandable metaphor for materialism,” Tank says. “The environment is the victim of our uncontrollable need for Thneeds. The Once-ler represents the robber barons of capitalism. The Truffula Trees, our precious natural landscape. Clothing is perfect to translate all of this in a digestible way [for children]. Clothing is a part of everyday life that we learn before learning to read.”

Penned in Dr Seuss’ studio in his home, an old observation tower up the coast from San Diego, California, the book was, at least in part, personal. “Geisel was fond of telling interviewers that The Lorax was inspired chiefly by the anger he felt as he watched builders engrave homes and condominiums into the hillsides below,” Dr Pease says. But it was also part of a bigger picture.

From the publication of Ms Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring in 1962 to the inaugural Earth Day in 1970, the modern environmental movement as we know it had just burst into life. The Lorax was a “product of the moment”, Dr Pease says, noting that the book was in turn used to help advance a slew of environmental protection laws. “Legislators quoted lines from The Lorax when they passed the Clean Water Act in 1972 and the Endangered Species Act of 1973,” he says. “But it wasn’t until the environmentalist movement adopted the book that sales took off.”

But the book wasn’t written for legislators or ecologists; it was written for children and this is where it has had a lasting impact. “I do think, in hindsight, it planted some kind of ecological mindset in me,” says Mr Ed Gillespie, who pored over it as a boy and grew up to be an environmental campaigner, entrepreneur and Greenpeace director (he also co-presents the podcast Jon Richardson And The Futurenauts).

Distilling complicated ideas into a message that even a child can understand is no mean feat. “People don’t appreciate how hard it is to write well in verse,” Mr Rob Biddulph, the author and illustrator behind a string of award-winning children’s titles including Odd Dog Out and Blown Away, tells MR PORTER. “My texts might take five minutes to read, but often take six months or even a year to write. The rhythm and content has to be perfect. Every single word counts. It’s a real challenge.”

Dr Seuss is a master of this. Biddulph lists him as “the gold standard that I have always aspired to”. But even for Geisel, The Lorax is next level.

“It’s deep, heady message, more difficult to grasp than Green Eggs And Ham. The Lorax embodies everything about what books are for and what they can do”

“It’s deep, heady message, more difficult to grasp than Green Eggs And Ham,” Mr Tank says, referencing Dr Seuss’ concise 1960 book, which was famously written using just 50 words. “[The Lorax] embodies everything about what books are for and what they can do.”

In fact, The Lorax displays a greater understanding of climate change than was probably available in most books aimed at adults at that time. Gillespie cites the concept of shifting baselines. This theory describes how human perception of environmental change is very often inaccurate. We see the world based on our own experiences and reference points, how we assume it was and not how it should be – just as the boy in the story can’t imagine the landscape of the past, lush with Truffula trees. He sees this barren earth as “the world that’s always been rather than what we’ve lost,” Gillespie says.

A recent study found that only two per cent of the human characters in Dr Seuss’ books are people of colour – and even these few are “depicted through racist caricatures”. The Lorax itself, however, becomes what its author never was: “a voice that speaks for the voiceless,” as Gillespie puts it. Described as “a sort of a man… shortish, and oldish, and brownish and mossy”, the creature appears when the first Truffula Tree is cut down, claiming to “speak for the trees”. Needless to say, the Lorax’s warnings go unheeded. And as the last Truffula falls, he removes himself from the scene, leaving the Once-ler, who was only ever interested in more, with one last word: unless.

It is only in the retelling of this story that the penny drops. The Once-ler shares the Lorax’s final warning, the crux of Dr Seuss’ book: “Unless someone like you cares a whole awful lot, nothing is going to get better. It’s not.” And with it, he gives the last Truffula seed to the boy.

“We understand that the Once-ler’s ultimate position is regret,” Gillespie says. It’s not the Thneeds that he really needs, but the trees. But by passing custody on to the boy, is the Once-ler himself shirking responsibility? “There is that problem: ‘Right, we fucked up – your turn’,” Gillespie says.

As an adult – and the culpability for state of the world that comes with it – reading the book to a child, the metaphor is not lost. But this message, “unless”, is what you make of it.

“The sad truth is that unfortunately it has fallen upon my generation, and those after, to pick up the tab and deal with the consequences of what the previous generations have done,” says actor and presenter Mr Cel Spellman, who fronts the new WWF podcast Call Of The Wild.

However, Spellman says that, ultimately, he finds hope in the words of the Once-ler: “Personally, I love that final line because, with the environment, climate change, it’s so vast, it can be overwhelming. You’re thinking, ‘What can little old me do to make a difference?’ This line is the perfect counter argument.”

“Unless someone like you cares a whole awful lot, nothing is going to get better. It’s not.” The Lorax was always about planting a seed.

The Lorax (50th Anniversary) by Dr Seuss. Photograph courtesy of Harper Collins.