THE JOURNAL

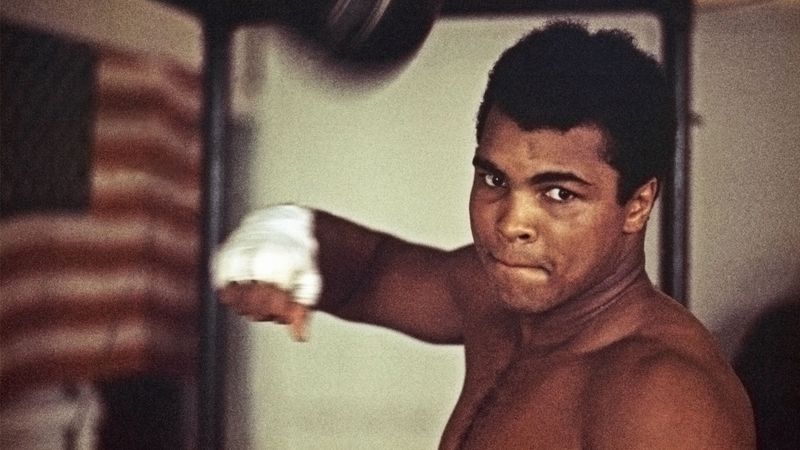

Mr Muhammad Ali during training, Miami Beach, 1970. Photograph by Mr Thomas Hoepker/Magnum Photos

The fighters who came after Mr Muhammad Ali and found themselves boxing his shadow.

Many boxers have won world titles and earned fortunes, but few transcend their sport. Of those who have enjoyed the recognition of the wider public, Mr Muhammad Ali is the most notable. Mr Ali became the heavyweight world champion at 22 and would defeat every rival of a gilded era. He was as durable as he was graceful in the ring, but it was his eloquence, wit and social conscience outside it that most set the Louisville fighter apart, and his refusal to be inducted into the Vietnam War made him a countercultural icon. “When I'm gone, boxing will be nothing again,” he once claimed. “I was the only boxer in history people asked questions like a senator.” But while “The Greatest” still casts a shadow today, the sport itself did not merely survive Mr Ali’s departure, it flourished, as Mr James Lawton’s new book A Ringside Affair: Boxing’s Last Golden Age recounts.

With so few of its protagonists attaining crossover appeal, boxing regularly undergoes existential crises. These tend to prove hysterical, but the sport has been unquestionably poorly served of late. Why? In a word: money. While greed has always been the lifeblood of prizefighting, the recently concluded “Mayweather era” was especially testing. Mr Floyd “Money” Mayweather marketed his unblemished record with such success that many promoters sought to follow suit, becoming tediously cautious in their efforts to steer their charges to the top – and keep them there. This meant fewer fights and long periods of inactivity for titleholders.

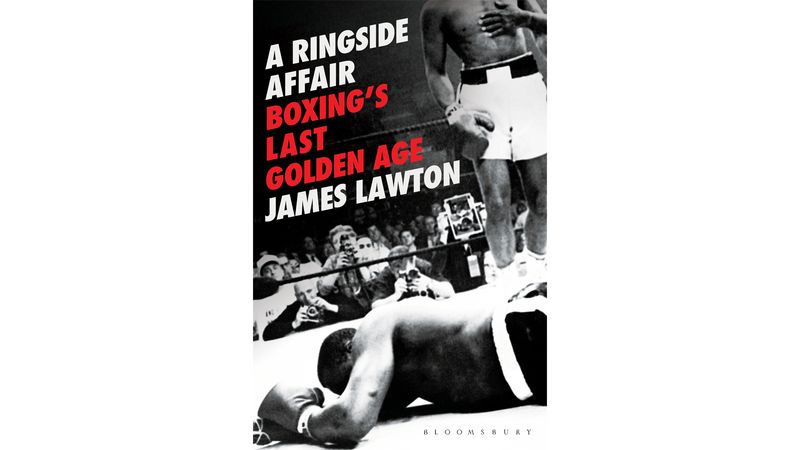

All the fighters of Boxing’s Last Golden Age tasted defeat. What set them apart was their response. Mr Lawton’s book, which is out this week, chronicles the sport’s vanguard from Mr Ali’s demise to Mr Lennox Lewis’ fight with Mr Mike Tyson in 2002. Where boxing turns today is anyone’s guess, but Mr Lawton’s ringside account is a timely reminder of what makes the sport so appealing.

Here, we take a look back to the fighters who followed Mr Ali and deserve to be remembered beyond the sport.

“The Fab Four”

Mr Marvin Hagler vs Mr Thomas Hearns, Las Vegas, 1985. Photograph by Mr Manny Millan/Sports Illustrated/Getty Images

After Mr Ali there were understandable fears over who could retain the wider public’s interest, but a quartet of fighters – Messrs “Marvelous” Marvin Hagler, “Sugar” Ray Leonard, Tommy Hearns and Roberto Durán – would allay them, their divergent styles resulting in some of the most captivating spectacles the sport has produced.

At eight minutes and one second, the bout between Messrs Hagler and Hearns at Caesars Palace in 1985 is often cited as the greatest in history. In round one, Mr Hagler threw 82 punches – not one a jab. Mr Hearns responded in kind, breaking his hand on his opponent’s head. A bloodied Mr Hagler prevailed in the third. “I never thought I would see anything so intense outside of war,” the writer Mr Budd Schulberg told Mr Lawton at ringside.

Despite giving up three inches in height and eight in reach, Mr Durán defied the odds to beat Mr Leonard, the technically sublime Olympic champion, in their first encounter in 1980 in Montreal. When asked who Mr Durán reminded him of as he approached the ring, Mr Joe Frazier replied, “Charles Manson”. The Panamanian mauled the greener Mr Leonard immediately, wobbling him with a vicious left hook in the second round before winning a unanimous decision.

Mr Leonard’s split decision victory over Mr Hagler at Caesars Palace in 1987 is still disputed 30 years on. Some saw Mr Leonard’s flashy but sporadic combinations as a ruse to sway the judges’ impressions, to others it was a triumph of craft over graft. No rematch meant the end of the Fab Four’s prominence. An embittered Mr Hagler retired and Mr Leonard, along with Messrs Durán and Hearns, was now on the decline.

“The Baddest Man on the Planet”

Mr Mike Tyson during his fight with Mr José Ribalta, Atlantic City, New Jersey, 1986. Photograph by The Ring Magazine/Getty Images

Attention would turn to a gauche, lisping heavyweight standing at just 5ft 10in. In 1986, a 20-year-old Mr Mike Tyson became the youngest heavyweight champion in history. He would rule with a baleful aura that was the product of both career-ending power and the sense that he wasn’t boxing to win so much as to administer beatings. Mr Lawton notes that for Mr Tyson, boxing had become “an epic of pain transference, from himself to the next victim staring bug-eyed in his apprehension”.

It is said that Mr Tyson’s opponents had lost before they’d stepped into the ring. Mr Tyson’s blood-curdling entrance to his 1988 clash with Mr Michael Spinks had his opponent visibly wilting – the fight lasted 91 seconds. At the weigh-in for his 1987 fight against Mr Tyrell Biggs, “Iron Mike” muttered, “If I don’t kill him, it don’t count.” In 2000, The Mirror even paid to advertise on the soles of the hapless Mr Julius Francis’ boots; five knockdowns (in a four-minute fight) ensured they got their money’s worth.

His 1990 defeat by Mr James “Buster” Douglas – on whom most bookmakers were not even taking bets – in Tokyo remains the sport’s biggest upset, but Mr Tyson had barely trained and was dropped heavily in sparring shortly before the fight. It was the first manifestation of an increasingly hedonistic lifestyle.

Mr Tyson’s life is a parable of money’s limitations. He earned more than any previous fighter, but after a dismal childhood that never left him, he simply couldn’t adjust to such a dramatic change of circumstance. Career earnings of $300m were soon dissipated, and by 2003, he was bankrupt. He would regain a version of the heavyweight title by beating Mr Frank Bruno in 1996, but after serving three years in prison for rape, he was no longer the unequivocal force in the division.

Mr Lennox Lewis

Mr Lennox Lewis vs Mr Francois Botha, World Heavyweight Championship, London, 2000. Photograph by Mr Nick Potts/EMPICS Sport/Press Association Images

The man who brought a faded Mr Tyson’s career to its de facto conclusion in 2002 was Mr Lennox Lewis, whose equanimity belied a brutality in the ring that helped him become the last undisputed heavyweight champion.

If that seemed inevitable given his technical proficiency and imposing physique, the path was not without setbacks. A shock first defeat by Mr Oliver McCall in 1994 saw him contemplate retirement. He was 29 and a multimillionaire – ample reason to walk away from a sport littered with warnings of overstaying one’s welcome.

Under the demanding tutelage of Hall of Fame trainer Mr Emmanuel Steward, Mr Lewis would tighten up his style and hone a highly effective jab, however his ascent to the sport’s summit was five years in the making and, as Mr Lawton recalls, “marked by drama, tragicomedy, intrigue, severe tests of both nerves and talent [and] deep frustration”.

A second improbable knockout defeat, to Mr Hasim Rahman in 2001, rekindled doubts over Mr Lewis’ resilience, but as before, his biggest enemy was complacency: he was filming Ocean’s Eleven two weeks before the fight and was badly out of shape.

With both losses avenged and victories over all pretenders to his throne, including Messrs Evander Holyfield, Vitali Klitschko and Tyson, Mr Lewis retired as the most eminent heavyweight of his generation.

Box set

Keep up to date with The Daily by signing up to our weekly email roundup. Click here to update your email preferences