THE JOURNAL

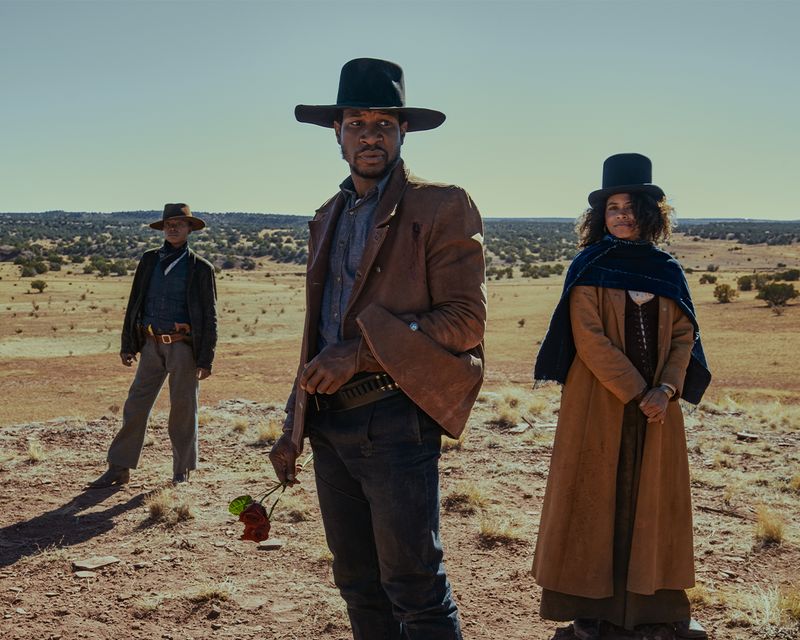

From left to right: Ms Danielle Deadwyler, Mr Jonathan Majors and Ms Zazie Beetz in The Harder They Fall, 2021. Photograph by Mr David Lee/Netflix

Netflix’s new western, The Harder They Fall, follows a denim-wearing, pointy-booted, valiant cowboy looking out from under his wide-brimmed hat as he traverses a rugged, desolate landscape. So far, so typical – except that this telling of the Wild West is rare. For one, the cowboy in question, played by Mr Jonathan Majors, is Black, as are the majority of his costars (Mr Idris Elba, Ms Regina King and Ms Zazie Beetz). It was directed by Black-British multi-hyphenate Mr Jeymes Samuel (aka The Bullitts), whose many skills include singing, songwriting, music producing, as well as filmmaking. Meanwhile, Jay Z serves as a producer, curating a mega soundtrack like no other Western that spans everything from reggae and afrobeats to new R&B tracks with Ms Lauryn Hill.

The Harder They Fall rides into town hot on the heels of a plethora of Black cowboy (and cowgirl) iconography across music, fashion and film that has been dubbed the “Yee-Haw Agenda”. Originally coined by pop culture archivist Ms Bri Malandroin in late 2018, the phrase plays on “the gay agenda” to describe the uptick in Black people donning cowboy looks in everything from magazines to music videos, with the suggestion that artists, creatives, activists and community groups were seeking to undo the whitewashing of cowboy (and traditional American) culture. The Yee-Haw Agenda allows African Americans to place themselves in the country’s rich history that often tries to erase or minimise their involvement and influence.

Around the same time, Black cowboy culture began to dominate music – most notably spurred by the release of Lil Nas X’s “Old Town Road”. Although the rap-country hybrid was controversially removed by Billboard from the Hot Country Songs chart, it went on to spend 19 weeks at the top of the Hot 100 from April to August of 2019, becoming the longest-running number-one song since Billboard’s chart debuted in 1958. Suddenly Lil Nas X was everywhere, rapping about horses and tractors, cowboy hat and fringed jacket in tow.

This reclaiming of an archaic American tradition also took the fashion world by storm via Black designers. Take Telfar’s “Telfar Country” show for AW19, which paid homage to Black cowboys by imprinting their image on jersey dress shirts and hoodies in a denim and leather heavy showcase, and LaQuan Smith’s SS20 collection, where cowboy hats and statement tees emblazoned with the words “hoedown” invoked the spirit of the West. Pyer Moss also paid homage to 19th-century Black cowboys such as Mr Bill Pickett, a rodeo star of that time, and featured real-life Black cowboy collective the Compton Cowboys in their campaigns.

From left to right: Messrs Kenneth Atkins, Roy-Keenan Abercrombie and Randall Hook of The Compton Cowboys, Los Angeles, 2021. Photograph by Ms Danielle Levitt/AUGUST

Naturally, cinema has followed suit. Ms Melina Matsoukas’ stunning 2019 drama Queen & Slim, which follows a Black couple on the run, shows Slim riding for the first time as Queen quips: “Nothing scares a white man more than a Black man on a horse.” Earlier this year, Netflix also released Concrete Cowboy, a tale of a Philadelphia community of Black equestrians keeping rebellious teens on the straight and narrow – no doubt inspired by the likes of Compton Cowboys, as well as Cowgirls of Color and Urban Saddles, which honour the traditions of horse riding, while also taking a keen interest in community activism.

So why now? Mr Quentin Tarantino once mused during an interview that westerns “more than any other genre that there is… reflect the decade that they’re in”. His favourite 1950s westerns were a product of the US of the Eisenhower era: tales of moral cowboys teaching the audience the values of honesty and integrity. Whereas the 1970s films, influenced by the aftershocks of Watergate, stressed the importance of not believing in the nation’s carefully constructed myths. Cowboys who had previously been seen as valiant heroes are reappraised as violent gun-toting menaces. In Tarantino’s own spaghetti western, Django Unchained, he created a Black protagonist that forced viewers to reckon with the US’s racist past.

Although it may feel like the Black cowboy is a 21st-century pop culture phenomenon, the truth is that people of colour were always part of cowboy-hood. The culture is a direct cousin of vaquero, the name given to Mexican horse-riding cattle herders, and as the tradition took hold in the mid to late-1800s African Americans made up a quarter of the vaquero population. This turned into a national fixation in the golden era of cinema via westerns, which, despite having a predominantly white facade, have also featured Black frontmen.

Samuel’s movie belongs to a long lineage of Black westerns that reflect the times in which they are made. Two Gun Man From Harlem (1938) and Sergeant Rutledge (1960) mixed the pressing issue of miscarriages of justice against African Americans into the plot, with protagonists wrongly accused of killing white women. In the 1970s, Black and white westerns critiqued corrupt power, as seen in the Mr Sidney Poitier-directed blaxploitation western Buck And The Preacher, where white people are portrayed as savages (a role the genre previously reserved for Native Americans). Meanwhile, Blazing Saddles made savages of cowboy cinema and the US at large in a dark comedy that is littered with race jokes.

Mr Sidney Poitier in Buck And The Preacher, 1972. Photograph by Columbia Pictures/Photofest

Later, films focused on making Black protagonists arbiters of justice like their white counterparts. Mr Mario Van Peebles, son of the blaxploitation pioneer Mr Melvin Van Peebles, directed and starred in the 1993 film Posse, where buffalo soldiers come to the rescue of a small Black prairie town to shield them from white supremacists. In the 1999 film Wild Wild West, Mr Will Smith plays a charismatic frontiersman named Jim West, who, in one scene, is subjected to a frosty reception in a room full of former slave owners as one thanks him for coming and “adding colour to these monochromatic proceedings”.

If Tarantino is correct, the rise in popularity of cowboys and westerns speaks to the fact that the US is wrestling with its identity after a tumultuous decade, returning back to basics to tell familiar tales but through a new lens. A reevaluation of the nation’s heroes and villains. And so what does The Harder They Fall say about where the US is or where it’s headed?

One could say it’s a corrected vision of America old and new – one that is more diverse than we usually acknowledge, and where Black people can have fun in the space rather than wallow (a deviation from the darker neo-westerns of late, such as No Country For Old Men, which are steeped in anxiety about a changing nation). It says a lot about how Black creatives want to centre themselves, flex their creative muscle and create vivid tales beyond explicit statements about their race or oppression. In a way, it’s what Malandro, mother of the Yee-Haw Agenda, intended. In March 2019, she told Jezebel that she didn’t create a social account tracking the style to note how “subversive” the trend is. Rather, she wanted to see a space where Black people could simply have fun being cowboys and girls.

It’s a statement that resonates with what the filmmaker has said about the role of race in The Harder They Fall. While it may be one of the few Black westerns to exist, it benefits from being born into a context where Black Americans are placing themselves in this history across music, film and culture. “It’s a film about a group of people, and, by default, these people are Black,” Samuel told The New York Times. “But their skin colour has nothing to do with the story. Which is what we’ve been waiting for, right?”