THE JOURNAL

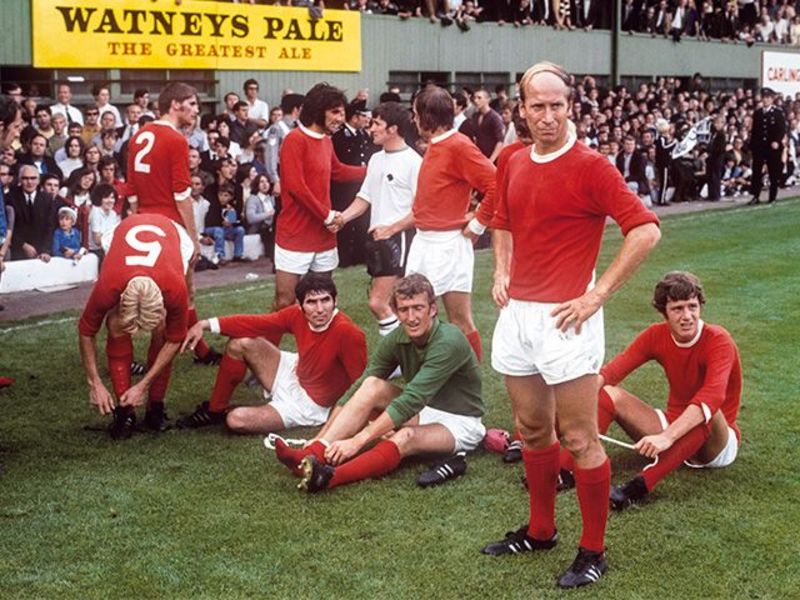

Sir Bobby Charlton and Mr George Best disappointed after a 4-1 defeat to Derby County in the final of the Watney Cup, August, 1970 Peter Robinson/ Press Association Images

Football was not so much transformed in the 1970s as fundamentally re-cast, its every surface refashioned in some lighter, softer, more obviously space-age material. By the end of the decade football may have looked in outline more or less the same, the players, the action, the stadiums – if you squint a little – almost unchanged. But at heart it was irreversibly altered, its trajectory reset, its public face glazed with a sheen of modernity. Albeit, not without some lingering imprint of its immediate past. If there is a particular magic to football’s great decade of change it lies perhaps in that peculiar sense of innocence that was still in place throughout the 1970s; the impression, however brief, of something transformed but still unspoilt.

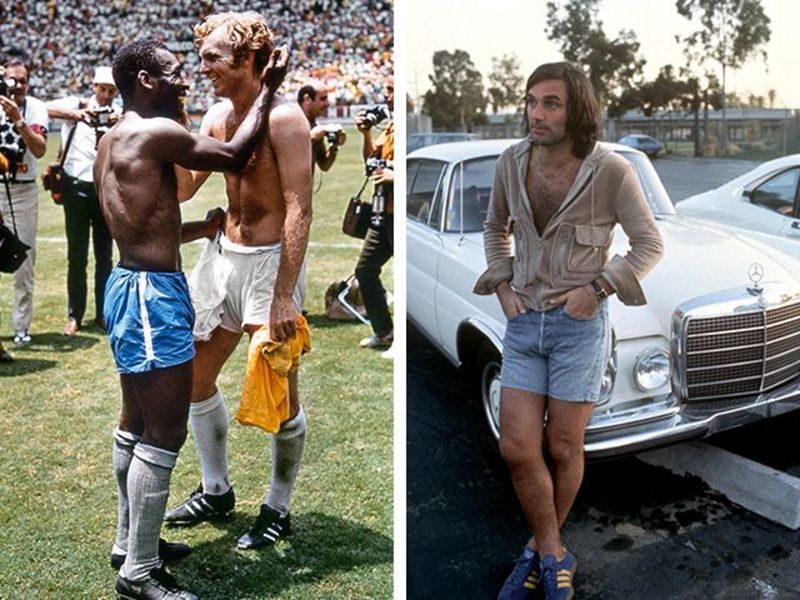

If, above all, one man could most embody this quality it was perhaps George Best, who first appeared midway through the previous decade as a gloriously unmarked teenager of preternatural footballing gifts. By the start of the 1970s Best was already established as an icon both of the sport and of the times too, a man in possession of the perfect hairstyle, the perfect smile, the perfect talent. And yet even in slightly haggard early maturity Best seemed to reach forward in time rather than back. Comparing him at the start of the 1970s with his Manchester United teammate Bobby Charlton – lone hank of oily hair scraped across his bald pate, a man apparently fixed in some distant wartime past – Best still seems impossibly modern, a one-man bridge from football’s folkish roots towards some brilliantly illuminated future.

Mr Best outside his shop in Manchester, 1970 Press Association Images

Footballers had always been popular heroes, darlings of the crowds from the first golden age in late Victorian Britain. This was a professional sport founded in a sense of stiff-collared razzmatazz, the trickled-down prosperity of the late Industrial Revolution creating for the first time a sense of leisure among the working population, the notion of disposable income, of half-day Saturday holiday, of a life beyond work, school and church. Seaside resorts flourished, museums and galleries and public parks were accessible via the new railway network. Out of this hunger for mass entertainment football was codified, repackaged and reborn as a spectator sport.

A hundred years later it was a similar reaching out, fuelled by the democratizing effects of mass media and a new sense of classless televisual glamour that would again transform the world’s most popular sport. The 1970s saw a significant growth in magazines and newspapers across Europe and the Americas, a huge spread in television ownership, and a general ramping up of the fascination with the broader entertainment industry. Footballers were hip, empowered by the new fascination with celebrity and a very teenage kind of pop stardom, and liberated from the old blue-collar structures of owner, manager and trainer.

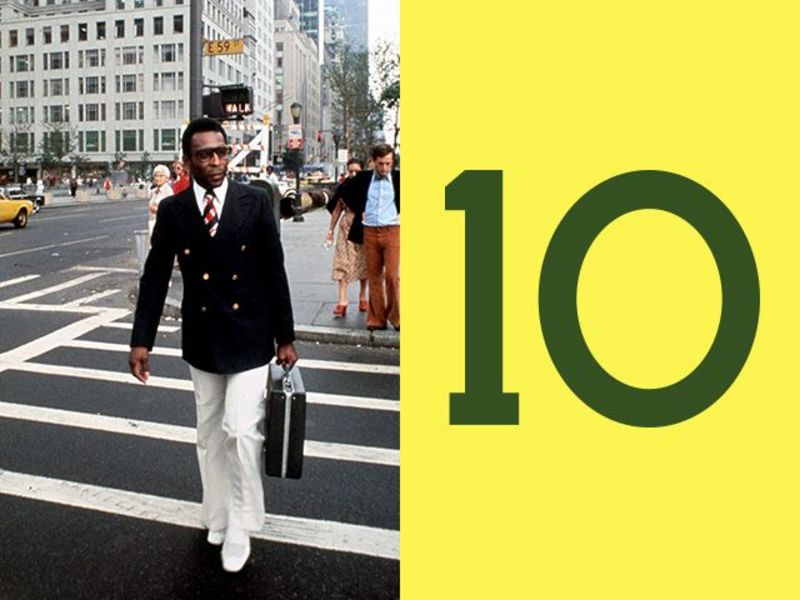

The opening shot in this transformation was the 1970 World Cup in Mexico, the first tournament broadcast live in Technicolor across every continent, and an enduring high point of expressive, imaginative football embodied by the great Brazil team of Pelé, Gérson and Jairzinho. In spite of which the 1970s was a decade that would be dominated by Europe. South America may have provided the founding sense of glamour, Pelé himself enthroned as a kind of disco-era monarch with his jumpsuits, his guitar, his appearances at Studio 54. But it was in northern Europe, home to the dominant superpowers of club and international game, that football really began to bloom across the mainstream.

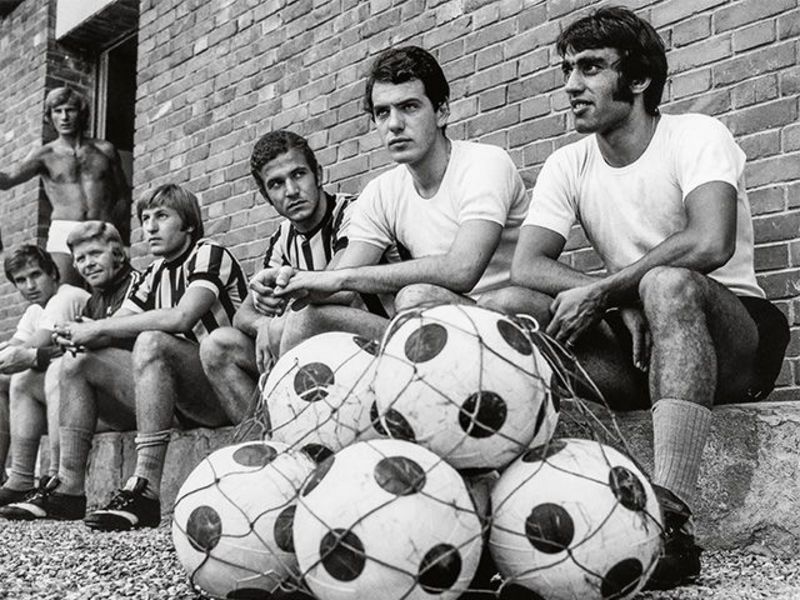

Juventus players line up at their training ground, 1971. Left to right: Messrs Gianluigi Roveta, Francesco Morini (standing), Helmut Haller, Gianpietro Marchetti, Luciano Spinosa, Roberto Bettega and Pietro Anastasi Popperfoto/ Getty Images

There was a synergy here with the wider entertainment industry. If the 1950s gave birth to the teenager and the 1960s to the pop star, then the 1970s was a time of broader celebrity promiscuity as the machinery of fame, hungry for new stars, turned its glance beyond the established powerhouses of music and film and landed, inevitably, on football.

Football was ready, too. At the start of the 1970s Europe’s super clubs had begun for the first time to pay giddily marked-up salaries to their star players – a process that would culminate in Pelé’s $1.4m a year deal at the New York Cosmos – as movement between the top leagues became more common and a distinct breed of intelligent, charismatic, often agreeably headstrong Dutch and German players began to dominate how football styled itself on and off the pitch. Even in its tactical patterns there was something intellectually coherent about elite European football as the idea of “Total Football” took hold, the notion that in the perfect team every player is able to play in every position, that every player is both a star and a cog in a brilliantly well-grooved machine. Football had traditionally been a feudally arranged industry, run by owners, directors and managers, with players as a kind of mud-bound human chattel. Total Football was by contrast a statement of player power, an aspirational, intellectualized style and a kind of academic footballing collectivism. With, it cannot be emphasized enough, really good hair.

Even the players’ kits had something stark and alluringly iconic about them, the block colours of the Dutch players’ brilliant orange strip, unblemished by advertising or players’ names, contrasting beautifully with the classic yellow and green of the Brazilians. For the first time football kits were tailored and modernised, a flattering accompaniment to the collar-length hair of an unusually handsome and charismatic generation of elite-level players. Frankly, tarnished in the modern era by advertising and kit manufacturers’ folly, football will never look quite so good ever again.

Portuguese star Eusébio and his wife in Lisbon, 1972 Agence FEP

What really stands out now is the players themselves, the best of whom were unapologetically articulate and entrepreneurial, carrying with them an ambassadorial swagger of entitlement. Johan Cruyff was perhaps the first of this new breed of Euro-cool footballers, with his Catalonian ranch, his supercharged Saab, his outspoken, unavoidably political public profile. Born and raised in Amsterdam where he emerged through the Ajax nursery to become the definitive embodiment of Total Football, Cruyff was also famous for his Confucian turns of phrase, and an irresistibly provocative charisma. His move to Barcelona in 1973 for $2m (paid to Ajax) and an annual salary of $600,000 made him into a superstar, but it also provided a seductively countercultural identity as an outspoken opponent of the dictator General Franco. To this day Cruyff remains father to the modern, all-conquering collectivist Barcelona style, the tiki-taka football of Spain’s world champions, and an unlikely emblem of Catalan nationalism.

West Germany’s captain Franz Beckenbauer was an equally formidable presence. A great and also revolutionary player in the role of ball-carrying central defender, Beckenbauer was born in ruined postwar Munich and went on to become the acme of the big-personality 1970s footballer, that breed of star player who seemed to have been recast as a kind of managing director in shorts. Beckenbauer was an emblem of control and authority in every team he represented, the son of a postman who went on to become the most influential man in German football during a 50-year ascent to global prominence that mirrored Germany’s economic triumph over the same period.

The look for the alpha male footballer of the 1970s was not so much beatnik with a ball as successful Californian advertising agency executive

This was an outward transformation too. The look for the alpha male footballer of the 1970s was not so much beatnik with a ball as successful Californian advertising agency executive. The wide-lapelled leather jackets, the non-ironical medallions, luxury cars and high-end walnut interiors: these were the trappings of the new superstar player, empowered by a transformative collision of burgeoning mass media and a sport in the process of opening itself out into the mainstream. Sponsorship became widespread for the first time, a process that really kicked into gear with Pelé’s infamous deal to delay the start of the 1970 World Cup final by pausing to tie his Puma boots.

Franz Beckenbauer and Kevin Keegan advertised Brut cologne and briefly Keegan became the most visible footballer in the world after his move to Hamburg in 1977, where he was awarded football’s first ever “face contract”, a deal that allowed him to exploit for his own gain his image rights, thereby unleashing a furious round of endorsement deals. Keegan modelled knitwear, trench coats, business apparel, golfing umbrellas, Cuban-heeled boots, hair gel and aftershave. He even made the sideways leap into music, having a top hit in Germany with the single “Head over Heels” and bestriding the mainstream pop press in England, where his poster would appear as a teenage collectible alongside Marc Bolan and the Osmonds.

Pelé crosses a Manhattan street, 1978 Rex Features

The notion of the high-visibility footballer-entrepreneur spread across Europe and into South America, from Pelé and Santos, with their world tours and exhibition matches, to Argentina’s impossibly cool Huracán team of the 1970s, to the glamorous Saint-Étienne of Michel Platini and Johnny Rep that briefly dominated the skies in France before imploding in a tax scandal, to the AC Milan team of Gianni Rivera, golden boy of Italian football. And yet for all that there was of course a sharper edge to this process, as the 1970s spawned a generation of more maverick footballing talents. Closer in spirit to the poetically doomed rock star, there was something intriguingly dazed and guileless about football’s pop idol star players of the 1970s. Best again is the defining figure here, the pop-kid footballer to end all pop-kid footballers, but also an oddly touching presence in the margins. Best’s journey from Belfast waif to icon of celebrity-sporting excess is well documented. But while there has always been a tendency to paint this breed of 1970s playboy-footballer as simply creatures of appetite – Best is said to have dated seven Miss World finalists and retained a fetish for brand new E-Type Jaguars – there was something far more nuanced about the young Best.

For all his excesses he played at the top level for 11 years, and stands outside the caricature, a frail and impossibly alluring talent cast into an unregulated world of temptation and predatory interests. Hounded by an aggressive mass market tabloid newspaper press, he decamped to the North American Soccer League where he lived in a loft apartment with his wife and young son, looking a little scarred and reformed and domestic behind the beard, a Lennon-like figure, in open retreat from his own celebrity.

Spectators on the Spion Kop at Hillsborough watch Leeds United and Manchester United draw 0-0, Sheffield, March 1970 Bob Thomas/ Getty Images

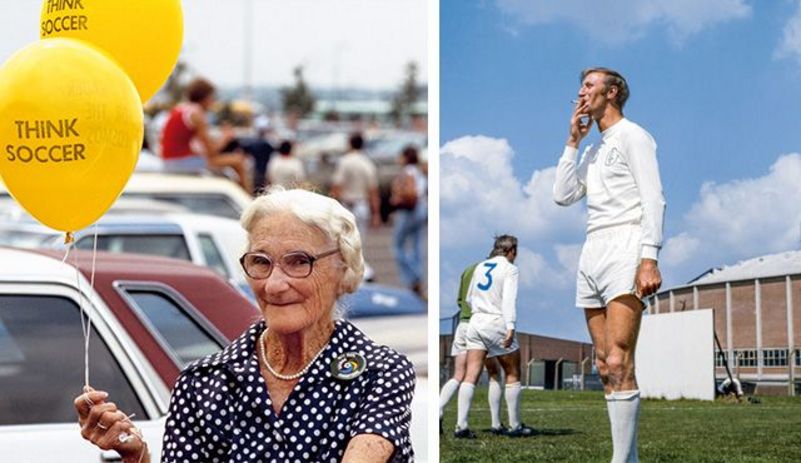

Left: The superstars of the North American Soccer League attracted people of all ages, including this New York Cosmos fan, 1978 Peter Robinson/ Press Association Images; Right: Mr Jack Charlton during a training session at Leeds, August 1970 Mirrorpix

Not that all of football’s 1970s mavericks were victims. In Germany Günter Netzer lived out a more controlled notion of high-end footballing glamour. A beautifully talented, beautifully blond, beautifully freewheeling creative midfielder, when he wasn’t playing for Borussia Mönchengladbach and Real Madrid Netzer owned a bar called Lover’s Lane, collected Ferraris – he almost died behind the wheel of one – and projected at all times a sense of delicate, soulful, Germanic style. Similarly in France the dreamily talented Dominique Rocheteau seemed to radiate a delicate, seductively photogenic allure, a quality that seemed to be located not just in the players themselves but in their surroundings, the houses and cars – high-end, but still on a recognizably human scale – and carrying with it a very specific sense of time and place.

There were of course broader shades to this process of opening out. Women had been almost invisible in professional football before the 1970s, but the rise of the mainstream megastar brought with it the emergence of the footballing power-wife. For all the fly-by-night promiscuity of the George Best-style maverick, high-profile fidelity was also a feature of football’s new alpha male. Johan Cruyff’s wife Danny Coster was a very visible partner in his glossily styled public life, just as Gerd Müller’s wife Uschi was always present at his side.

If football’s burgeoning celebrity muscle allowed it to act, at times, as a progressive social force, this was most obvious in the projection of black footballers into the mainstream. The presence for the first time of successful black athletes on television screens around the world is an often-overlooked effect of Brazil’s 1970 World Cup triumph. Brazil’s players were brilliant, but they were also incidental pioneers, inspiring a generation of black athletes in Europe to express themselves without fear on the pitch. In England Cyrille Regis, Brendon Batson and Laurie Cunningham came through together at West Bromwich Albion and were rather awkwardly dubbed “The Three Degrees” by their manager, posing even more awkwardly with the soul band of the same name, who looked utterly baffled by the entire experience. Cunningham later moved to Real Madrid and charmed a generation of Spanish football fans, living like a pop star off the pitch and producing occasional moments of genius on it, before eventually dying in a car crash outside Madrid aged just 33.

Left: Mr Bobby Moore and Pelé swap shirts after Brazil beat England 1-0, Guadalajara, Mexico, June 1970 John Varley/ Offside Sports Photography; Right: Mr Best, Los Angeles, 1976 Rex Features

In the 1970s the periphery also became a part of the spectacle, most notably in England where for the first time the football crowd began to find itself associated with a broader youth culture. Not only were crowds younger, they were better dressed too, as the football casual, younger brother of the football hooligan, became a fixture of away ground, train station and match-day city centre. The appearance of designer labels and sharp European tailoring on England’s crumbling terraces owes something to regular away trips in the European Cup in the late 1970s. Liverpool fans in particular were notorious for returning home laden with Italian sportswear – some perhaps even paid for – from games in European capitals as clothing brands like Kappa, Diadora and Sergio Tacchini became unlikely cult labels.

There was, of course, a dark side to the new terrace culture. It has been argued that football hooliganism had very little to do with football and plenty to do with alienation, boredom and casual criminality. Dispossessed and disenfranchised youth was a theme of the decade that saw violent social change and the rise of the punk aesthetic. It was perhaps natural that some of this tribal aggression should attach itself to football, which became a stage for casuals, skinheads and the kind of self-identifying hooligan gangs. This sense of a wild frontier on the terraces brought football further into the mainstream as a news item, a political issue, and a theatre of youthful confrontation.

The overlap with mainstream fashion and celebrity would find its ultimate expression in the North American Soccer League. The NASL was a razzmatazz-laden football start-up whose ersatz franchisees included Team Hawaii, Chicago Sting, San Diego Jaws and of course the brilliant, lamented, unrepeatable New York Cosmos. For a two-year period during which the Cosmos played in front of 80,000 in the Giants stadium, major celebrities frequented the home dressing room and Pelé and Beckenbauer both wore the Cosmos jersey (designed, incidentally, by Ralph Lauren), they were briefly the most glamorous football team on the planet.

Mr Dino Zoff, Milan, June 1974 Mondadori/ Getty Images

The Cosmos was founded in 1970 by Warner Entertainment executives Ahmet and Nesuhi Ertegun. After five fallow years the team and the league itself were transformed completely by the signing of Pelé on a world-record deal and to a contract that, for tax reasons, had him listed as a “recording artist” with Atlantic Records. The NASL bloomed in the white heat of the Pelé years as the Los Angeles Aztecs signed George Best and Johan Cruyff.

It couldn’t last. Pelé retired in 1977 and the NASL folded seven years later, by which stage the 1970s had already elided into a more urgently predatory new world. Football has changed beyond recognition in the years since. It stands before us now transformed into an impossibly starry global entertainment property, a fully realized sporting world that can seem at times only distantly related to the mud-bound, strangely delicate stylings of the 1970s – its last real decade of innocence.

The Age of Innocence: Football in the 1970s edited by Reuel Golden (Taschen)