THE JOURNAL

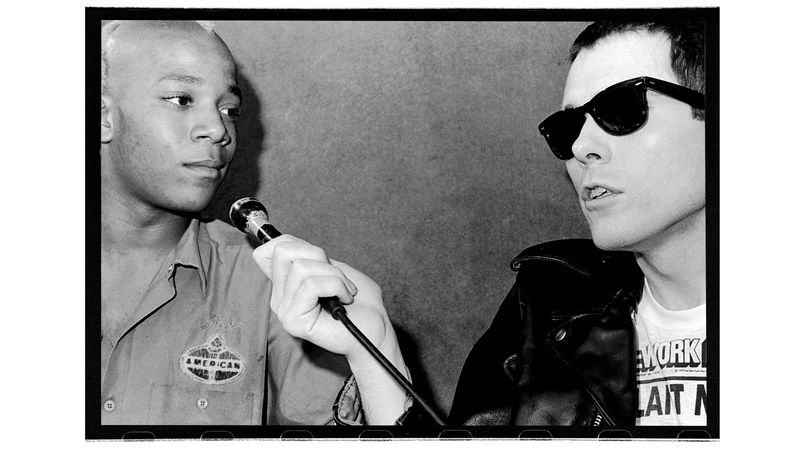

Mr Jean-Michel Basquiat in Downtown 81, 2000. Photograph courtesy of Metrograph Pictures

“New York has gone to hell,” the President of the United States tweeted in mid-October, three weeks before a general election. It was quite a take, you have to say, no matter how earnest or good faith it may or may not have been intended. But the idea is not entirely unique to him. Everywhere we go online these days, the media, their gadflies and antagonists, as well as New Yorkers both at home and far afield, are gleefully postulating that the city is dead, or so totally not dead, or “dead,” ironically, or, like, extremely lit for underground pandemic parties.

With the weather in the Northeast still just hovering, Road Runner-like, above the chasm of winter temperatures, and the entire city eating al fresco in what were once bus or bike lanes while so many of the city’s offices remain closed for business, there is a kind of Weimar-era deliriousness to New York at the moment. Gone are many of the more fortunate, who have perched at beachfront or countryside second homes, but also absent are the hordes of tourists flooding through every nook and cranny of the town. Some shops have reopened; many never will again. The municipal infrastructure is functioning (as well as it ever does in NYC). So, says the writer and urban historian, Mr Luc Sante, “when people say ‘New York is over’, we have to ask: ‘Over for whom?’”

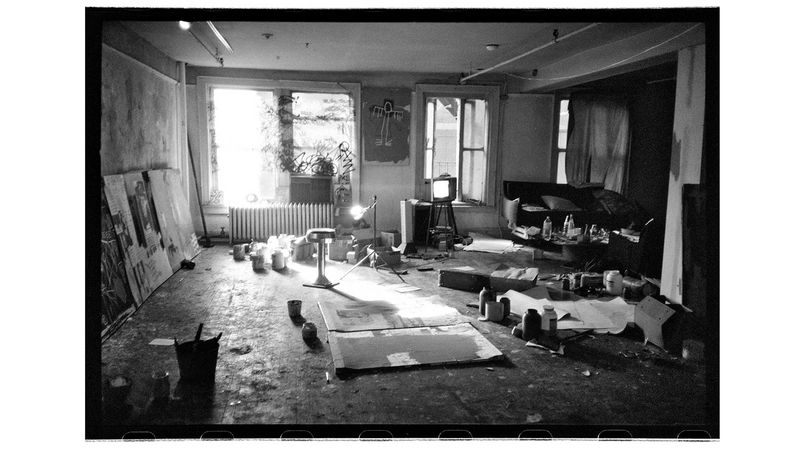

Interior of Mr Jean-Michel Basquiat’s Crosby Street Studio, New York, 1983. Photograph © Roland Hagenberg

If the identity of the city and what it stands for in the popular imagination seems to be once again in flux, under discussion and up for grabs, it may be worthwhile to revisit the last time the city was in such an active mode of recreation; the last time, incidentally, it faced such overt abandonment by leadership. In the 1970s, then President Gerald Ford denied New York a bailout it had requested and, in so doing, told the city to “drop dead”, in the words of the Daily News.

What followed, in the period between 1975 and 1983, “is often portrayed as the city’s low ebb,” says Mr Sante. He is talking about the 1977 blackout, the near bankruptcy, the garbage and transit strikes. “But those barely affected the likes of us,” he maintains, “us” being artists, intellectuals. “We coped, just as we coped with life in crumbling tenements. We had no money, so street crime wasn’t particularly a problem as long as you had gates for your windows,” he recalls. “But whatever hazards and inconveniences were around, they were tolerable because there was one very large convenience: living was extremely cheap – rents, food, secondhand everything. And cheap living is the one baseline necessity for a community of artists and suchlike.”

For Mr Sante, who was born in Belgium but grew up in and around New York, this was the city’s great moment. He had only recently graduated from Columbia, and had not yet become a full-time writer and one of the great historians of the city. Many of his experiences and the characters from this era feature prominently in Maybe The People Would Be The Times, Mr Sante’s newly released collection of essays.

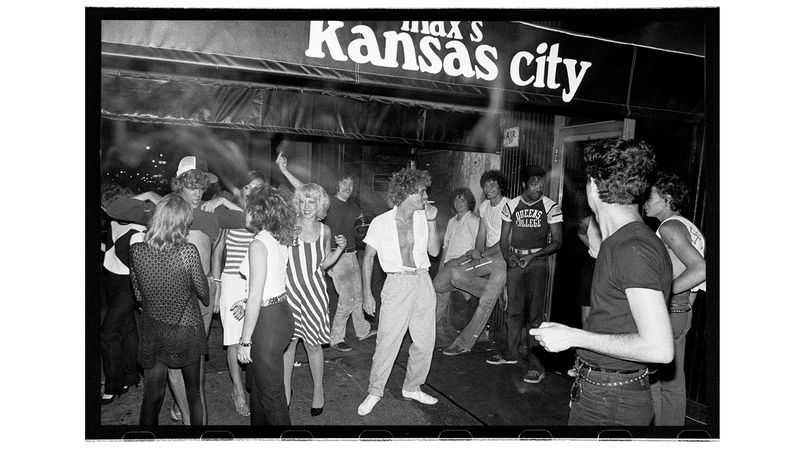

Mr David Johansen and others outside of Max’s Kansas City, New York, August 1980. Photograph © Bob Gruen/bobgruen.com

As he describes it, the images of New York that have come down to us from that time are so often very grim – the Lower East Side reduced to rubble, the Bronx in flames – while at the same time our perception of the spirit of the city circa 1980 is one of a Bohemia in full blossom. This was the cracked concrete through which Mr Jean-Michel Basquiat would emerge, home to the rough glamour of the artist-favoured bar Max’s Kansas City (from which Mr Andy Warhol’s Factory would spring), and also to the disco exuberance of Studio 54.

“Of course, New York was still the capital of the world,” Mr Sante says, “even as it was a sink. There was a built-in glamour to the place that underlay even the most threadbare undertakings, which there wouldn’t be in most other cities. That glamour was mostly residual – it didn’t come from television or Broadway or Wall Street or whatever other capital-of-the-world appurtenances were still in effect, but from the accrued past, which was visibly all around. We didn’t think of the city as a failed state because we didn’t think in those terms. We didn’t want to rule the city – we didn’t want anyone to rule the city. I guess maybe we thought of it as what [author] Hakim Bey called a ‘pirate utopia’.”

This inmates-running-the-asylum energy of the semi-autonomous zone of New York would fuel a new wave (or, as they might’ve had it, “no wave”) of artists, from Mr Jim Jarmusch to Ms Patti Smith and, of course, to Mr Basquiat. From 1979 to 1982, as he made the transition from street artist to art world sensation, Mr Basquiat was a regular at both the Mudd Club in Tribeca, and on the public access show TV Party, which was broadcast only Uptown. The show was hosted by Mr Glenn O’Brien, an editor of the newly launched Interview magazine.

Mr Basquiat’s first visit to TV Party, with Mr Glenn O’Brien, 24 April 1979. Photograph © Bobby Grossman

At the time, the city, as Mr O’Brien would later describe it, was folded up so that designations of Uptown and Downtown lost all meaning, with high society types and low-lifes rubbing shoulders at the same parties, mixing highbrow and lowbrow in the conversations they shared. The world felt wide open, accessible, up for the taking. And the film that Mr O’Brien wrote and produced, Downtown 81, which starred Mr Basquiat and was finally released in 2000, is both a portrait of and testament to the rough and ready hustler spirit of the age.

In the film, a 20-year-old Mr Basquiat plays a version of himself, an artist trying to sell a painting against the backdrop of a physical city in ruins. Wearing his huge funeral coat, and showing off his emergent mix-master style that would become so magical later in the era – pairing wide-shouldered power suits with T-shirts, Comme des Garçons with thrift-store fare, he is a painterly Puck tumbled straight out of our style dreams, guiding us through the nearly allegorical dystopia of the New York and its art world. “I was free,” he says, “but the city wasn’t – the price of the subway had gone up.”

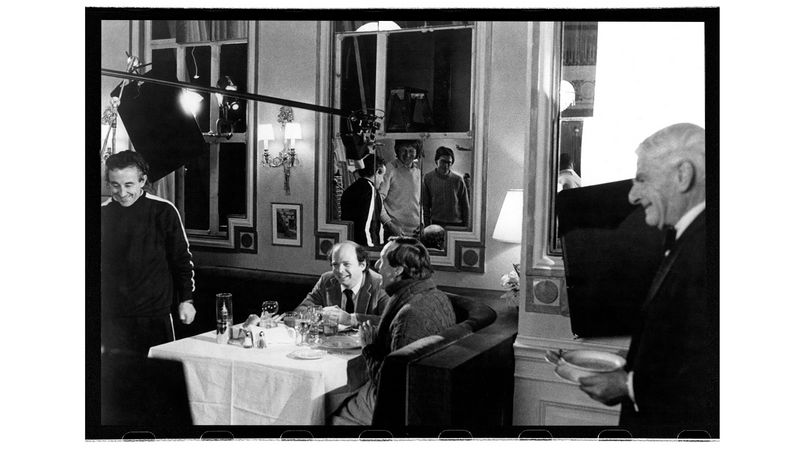

A slightly different but similarly resonant spin on the artist exploring the city was expressed by Mr Wallace Shawn, playing a version of himself, in the New York story My Dinner With Andre, released in October of 1981. “The life of a playwright is tough,” Mr Shawn-as-Wally says in the sort of mock melancholic monologue to open the film. “It’s not easy, as some people seem to think… Today, I had to be up by 10 in the morning to make some important phone calls. Then, I’d gone to the stationery store to buy envelopes. Then, to the Xerox shop. There were dozens of things to do.”

From left: Messrs Louis Malle, Wallace Shawn, Andre Gregory and Jean Lenauer on the set of My Dinner With Andre, 1981. Photograph by New Yorker Films/Everett Collection/Alamy

Like Downtown 81, My Dinner With Andre is a meditation on the worth of our creative work, on the weight of money, on the joys and stresses of the city. Where_ Dinner_ is elliptical and perhaps a bit ambivalent about New York, Downtown slips a bit toward fantasia, with Mr Basquiat in search of the “diamond brick road”, he would later find in real life. What unites the two is the palpable pop of creativity, with artists feeling free to explore their media; the sense that, right then, for a brief, fleeting moment, New York was not just the capital of the world it likes to think itself to be, but the capital of possibility, that the artists could shape the world to come, that it all might turn out OK.

Now, as the ad hoc dining tents roll into the streets where protestors marched every day through the summer, New Yorkers once again entertain themselves with the artist’s initial impulse: who are we to be? What will we make of ourselves, of the world in which we live, and the city we love? The city itself still is not, at all, anything close to free – but, maybe that accrued past that Mr Sante spoke of, the city’s history of a refuge and resource, remains.

Perhaps that is the point of NYC. Then and now, the physical domain is just a portal into fantasy – the fantasy of where we want to live and the “we” we hope to be.