THE JOURNAL

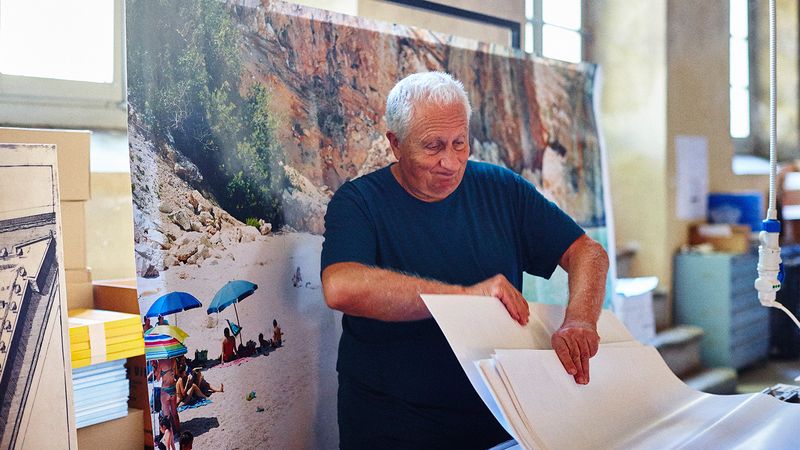

Mr Vitali sorts through prints in his studio, a former forge tucked behind Lucca’s San Giorgio prison

_The master of seaside photography takes MR PORTER on a tour of his awe-inspiring home in Lucca, Italy, and reveals why he hates beautiful pictures

._

Most of us, taking a first look at Mr Massimo Vitali’s breathtaking photographs, might be forgiven for thinking that they’re rather beautiful. Shot with a large-format camera from 18ft of scaffolding, they typically feature the general public at leisure in resort or beach environments, each individual reduced to a speck against spectacular and often overwhelming natural scenery. The compositions are clever and pleasing. The colours are blissfully washed out. Often one key shade predominates – the white of the snow at a ski resort, the blue of the sea on a beach, which gives each image a cleansing, transcendental feeling. Beautiful, right?

Wrong. Well, at least, according to the man himself. “I hate beautiful pictures,” he says, when MR PORTER meets him at his home in Lucca, Italy, itself a rather – for want of a better word – beautiful Tuscan town, still surrounded by its original Renaissance-era city walls. Mr Vitali lives here in a deconsecrated 14th-century church, its vast interior repurposed for modern family life via a series of stand-alone internal structures and decorated with tastefully minimal Italian furniture – from an 18th-century linen closet to modernist daybeds and lurid armchairs. It’s beautiful too, really. But Mr Vitali is not in the business of beauty. It just seems to happen to him.

An iron staircase creates living and sleeping spaces in Mr Vitali’s home, a deconsecrated church

“I mean, I’ve been consistently trying not to make beautiful pictures for a long time,” he says. “There are two things that really bug me, one is the ‘beautiful picture’ thing, and the second is ‘where was this picture taken?’. Because if someone asks that, then… you’ve failed. My pictures are not geographic. They should be banal, maybe, but not beautiful and they should not discover a territory. They are about millions of other things.”

It’s true. Though many of Mr Vitali’s photographs are taken in blissful locations, such as the secluded coves of Spargi, an island near Sardinia, or the dazzling white rocks of Sarikiniko, Milos, Greece, they are more than just aesthetically pleasing. In fact, they present us with a more interesting contradiction: the majesty of nature versus the unthinking inanity of tourism. “My subject,” he says, “is trying to understand what we’re doing, what I’m doing, what the people that I photograph are doing.” It’s a subject filled with irony – the queueing, fussing, splashing people in each location seem completely unaware of the bigger picture. That’s something only we as viewers, and Mr Vitali as the photographic voyeur, are privy to.

Mr Vitali at home

Irony is not everything, though. As well as being a great photographer, Mr Vitali spins a fantastic yarn. This is apparent as he walks MR PORTER around Lucca, telling us about Santa Zita, whose miraculously preserved body has been on display in the town’s San Frediano church since 1580, or the local prison next door to his studio, where Mr Chet Baker was held for more than a year in the 1960s, and Lucca’s young women now gather to call to the inmates as they play football. His interest in and curiosity about the world, about people, about the absurdity of it all, means that, in Mr Vitali’s images, the closer you look, the more you see. “What is important,” he says, “is the complexity of the thing. The idea that you have many, many layers within a picture, you can’t look at just one. And the more contradictory things, the better.”

A 1990s photographic studio – still owned by the church of Lucca – in Mr Vitali’s back garden; hard at work in his studio

When he talks about the photos, you see what he means. In one (see below), he points out a row of houses in Sardinia that reminds him of a nativity diorama, the bathing figures beneath like a painting in the Campesanto, Pisa, depicting souls in purgatory. Another landscape in Brazil, predominantly white, is related to the all-white “achrome” paintings of mid-century Italian artist Mr Piero Manzoni. Elsewhere he spots narratives among his subjects. This old woman, he says assuredly (though he has no way of knowing), is going into the sea for the first time, coaxed by her young relatives. That woman, with her baby, is like the Madonna and child.

“My way of observing,” he says, “… it’s about a way of connecting the people [in the pictures]. If I didn’t take the pictures, I wouldn’t give a shit… I wouldn’t be interested in what people do. But the idea of taking the pictures – I think it makes me have a different approach to life.”

Mr Vitali cycles between his house and his studio; the streets of Lucca

Mr Vitali has been taking pictures ever since, at the age of 12, he was given a medium-format camera by the photo historian Mr Lamberto Vitali (no relation, despite the surname, but a friend of Mr Vitali’s father). This was in the 1950s. “At that time,” says Mr Vitali, “when somebody gave you a camera, it was not like now. Now, you get a camera, you’re like, ‘So what?’ and throw it away. But then it was a commitment… you couldn’t get a camera and not use it.”

This early interest in photography developed quite naturally into a career after Mr Vitali moved to London to study at the London College of Printing and then began working as a photojournalist and, subsequently, in film. “I did movies, as director of photography… advertising, that terrible stuff,” he says. “But interesting from the technical point of view.”

The garden at Mr Vitali’s home; a kitchen conservatory adjoining the sacristy

Perhaps surprisingly he didn’t start taking artistic photographs until the 1990s, when he was in his fifties. Up until then, he says, he hadn’t really considered that art and photography could intersect. It was the work of the Düsseldorf school, photographers such as Messrs Andreas Gursky and Thomas Struth – who like Mr Vitali, work with large format cameras – that changed his mind. He still gets his pictures framed in Düsseldorf, after they are printed in Milan.

Today, Mr Vitali works in a manner that seems unusual by contemporary standards. There’s the scaffolding, of course, which follows him everywhere he shoots (though if he’s shooting internationally, he rents), along with his long-time assistant Mr Giovanni Romboni and a team of one to two others. But there’s also the fact that, since the early 1990s, when he produced the first of his beach images, he has taken something in the region of 5,000 exposures in total (they are titled by their chronological number). Practically, this means just one or two in a typical day’s shooting. And this is not because he’s continually setting up the shot; working in film, he says, taught him to decide where to put the camera at lightning speed. Rather, he spends much of his time both thinking and watching, waiting for the perfect moment. “You start following things,” he says. “And you think, ‘Oh, but if that goes here, and then he looks here…’ And then you start thinking what people are thinking.”

The artist prepares artichokes at his kitchen island, which stands in front of his bedroom

Mr Vitali has a need for complexity, whatever the medium – he recently collaborated with high-end French swimwear brand Vilebrequin to produce a range of swimshorts printed with one of his photographs. “I thought it was rather above the normal commission work… it became a little deeper than you would have thought,” he says, when asked why the project appealed to him. By this he refers to the fact that he not only shot an original image for the design – he deliberately chose to visit a non-typical beach, surrounded by trees, to create irregular stripes of white and green next to the blue of the sea – but added a “complication” to it in that several of the swimmers depicted, in a mise en abyme, are wearing the swimshorts themselves. He likes them, not only because they are “different from what you might think”, but because, contrary to the usual tinkering and post-production that goes on in the fashion industry, he was able to keep the photograph, as a print, more or less how it was taken (though he did concede to removing one topless bather). “I think in a picture you have to let things take over,” he says. “You have to accept the picture for what it is. You don’t have to have everything perfect. The imperfections are the interesting part.”

Such a considered approach to image-making is pretty much the polar opposite of what generally goes on in the contemporary world, where everyone has a camera phone and is constantly clicking away. And this is something Mr Vitali is aware of, and curious about. “People always say that more pictures are taken every day now than in the first 100 years of photography,” he says. “Exactly. But why?” The moment you scrape beneath the surface, problems appear. Everything… it’s very superficial.” This is where the beautiful question comes up again. For Mr Vitali, it’s not enough to be beautiful – mix fantastic composition and wonderful light and you have a sunset. Or rather, a “#sunset”. As he puts it, “That’s a total genre.” Mr Vitali’s photographs, on the other hand, are anything but generic – they need to be seen up close and read. They are large for a reason. “It would be difficult to find a hashtag for my photographs,” he says, laughing. “Let’s put it that way.”

Mr Vitali’s Works

Mr Vitali’s photographs bear close reading, and no one is better at doing so than the man himself. Here he takes us through a selection of our favourite images.

“Sacred Pool Russians”, 2008

“This is a Roman baths on top of Pamukkale in Turkey. Pamukkale is a white hill where the hot water flows down the valley and goes into little pools. The problem is that when we went there was very little water, the white on the pools was horrible, there weren’t people; it was disgusting. So I went to the source. This is where all the hot water from Pamukkale comes from. And this was the original Roman pool and here were the columns from the temple. People sit on the columns. It was funny because I asked the guy, the guard… I couldn’t understand where these people came from. And I asked, ‘Where do these people come from?’ And he said, ‘Wednesday? Russians!’”

“Cefalù Orange, Yellow, Blue”, 2008

“This is in Sicily, Cefalù. In Naples they make these nativities of Christ, these little diorama landscapes with houses. And the houses are exactly like this. And here we have the sea. So it’s a total fantasy world. And in this total fantasy world, what attracted my fantasy was three things. First of all there are these three men [bottom centre]. Each one has different coloured trunks: orange, yellow and blue. So this already attracted my attention. Then, this mother [bottom right]… this could be out of any Renaissance painting. Except for the inflatable.”

“Porto Miggiano Horizontal”, 2011

“I would say that this fits into the idea of humans being a colony of mammals. Somehow we’re made to live on the coast, like penguins… penguins don’t venture, they don’t go anywhere. They stay on the coast because there they have nutrients, they can swim, they can fish, so they stay on the coast. And we normally stay on the coast, if you look at the percentage of people who live near the coast as opposed to the people who live in the middle of nowhere, it’s incredible.”

“Sarakiniko”, 2011

“Sarakiniko is a place on the island of Milos, in Greece, and it has these fantastic white formations. Obviously everything looks different on white. Photography has always been about strong contrasts, long shadows, dramatic light. So I like to do the opposite thing. I don’t like shadows – I like white. If you know your technique and you can balance the white, you can have hundreds of different types of white.”

“Spargi Cala Corsara”, 2013

“Spargi is a little island off La Madelena, which is off Sardinia. The place is fantastic, it’s absolutely gorgeous. And being an island off an island off another island, what happens is that it’s totally deserted but at a certain time of the day you have tourist boats that arrive and you have 300 or 400 people who disembark. This picture doesn’t have a sky. The sea is totally enclosed. It doesn’t let you breathe. And this I like. Also this idea of these people getting there… They get to this fantastic place and they arrive and don’t really know what to do so they start taking pictures of one another, then they go to the water but first they have to put the towels down but they don’t know where to put them down… People are really embarrassed. They would be better off in a resort.”

“Cala Maiolu Coda”, 2014

“Here you have another beach. The people are now embarking on one of the boats. We don’t see the boat but you see this fantastic place, really dramatic, and people don’t seem to get the idea behind this strong landscape, they’re behaving normally. There are contrasts. Things that don’t really go together.”