THE JOURNAL

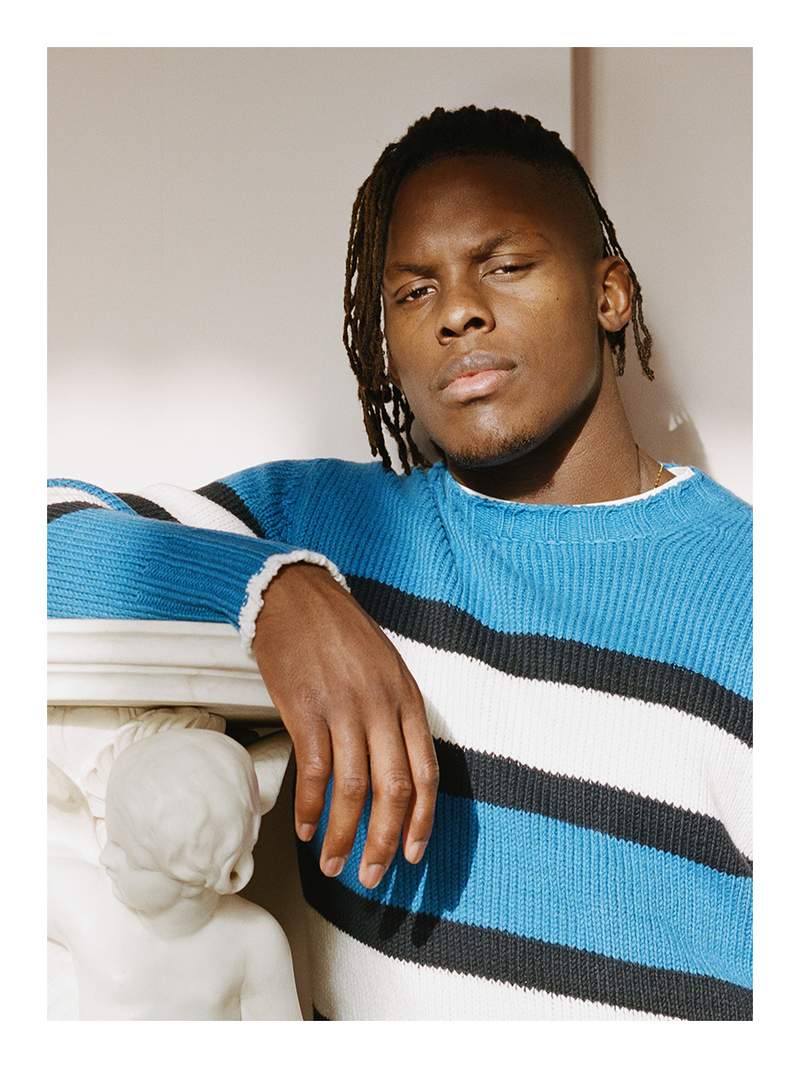

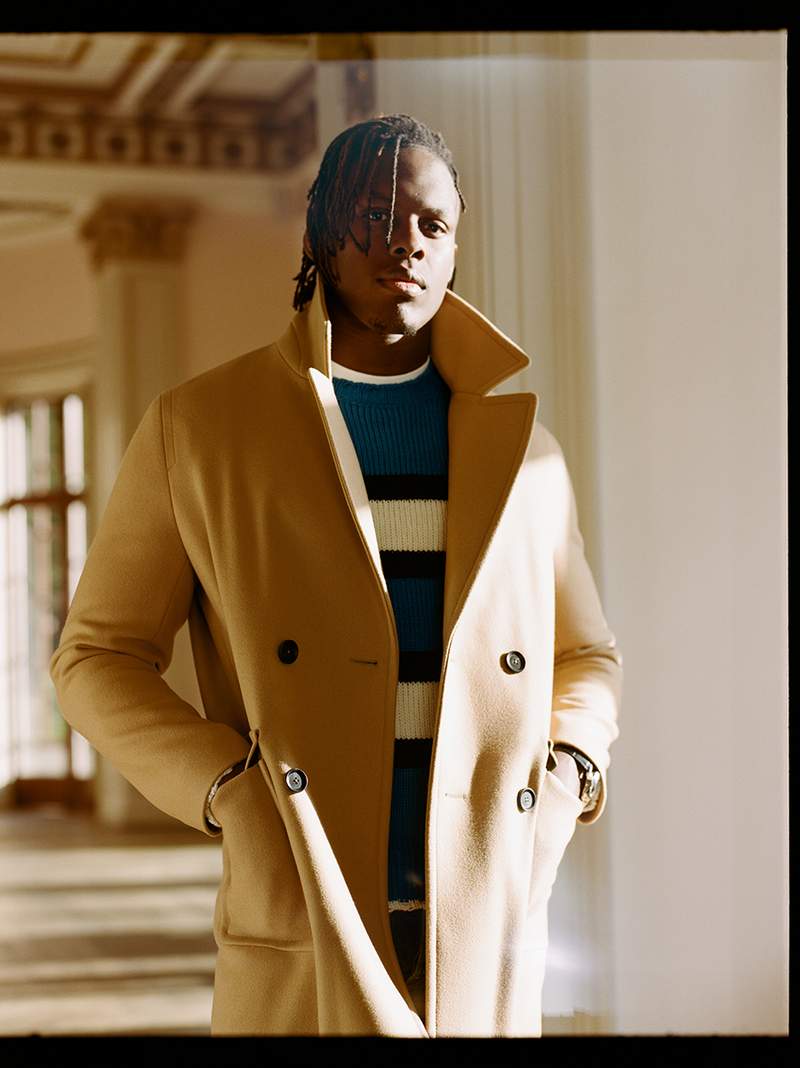

Ask a member of the All Blacks, New Zealand’s previously all-conquering rugby team, what it’s like to face Mr Maro Itoje on the pitch, and the answer is likely to be accompanied by a wince. In 2017, aged just 22, the Londoner tormented the then world champions on his first test start for the British and Irish Lions, and left the field in Wellington with his name booming around the stadium to the tune of The White Stripes’ “Seven Nation Army”. Last October, the anthem got another airing at the semi-final of the 2019 Rugby World Cup in Yokohama, when blindside flanker Mr Itoje put in a towering performance for the England team that ended New Zealand’s hegemony with a seismic 19-7 win.

Since making his first-class debut for Saracens less than seven years ago, Mr Itoje has won rave reviews for his dynamism, his ability to dominate opponents and bend matches to his will. He has already been named European Player of the Year and twice shortlisted as World Rugby Player of the Year; he has been part of four English Premiership-winning and three Heineken Champions Cup-winning sides, as well as being a Grand Slam champion and a World Cup finalist with England. It’s fair to say, though, it’s the All Blacks that bring out the best in the young colossus of English rugby.

“They’ve set the standard, and when you set the standard, you put a target on your back,” he says, one month on from that momentous night in Japan. “They’ve been leading the race for a long time now, so I was very happy to be part of the team to chop them down a little.”

Sadly, for Mr Itoje, the England team was itself chopped in the final of the Rugby World Cup, and the failure to “finish the job” is something that clearly still rankles. “By a country mile, it was the toughest experience I have ever had,” he admits of the 32-12 loss to South Africa. “Have I fully processed it yet? I don’t know. I think it’s one of those things that you have to try to learn from and move on.”

We are sitting in the café at Gunnersbury Park in west London. On this particular lunchtime, the other tables are occupied by mothers and toddlers in pushchairs, all of whom seem oblivious to the sporting hero in their midst. Mr Itoje doesn’t seem bothered about that, though. In fact, he admits it’s a relief after the “buzz and excitement” of the World Cup reached such a pitch that he felt it necessary to temporarily remove himself from social media.

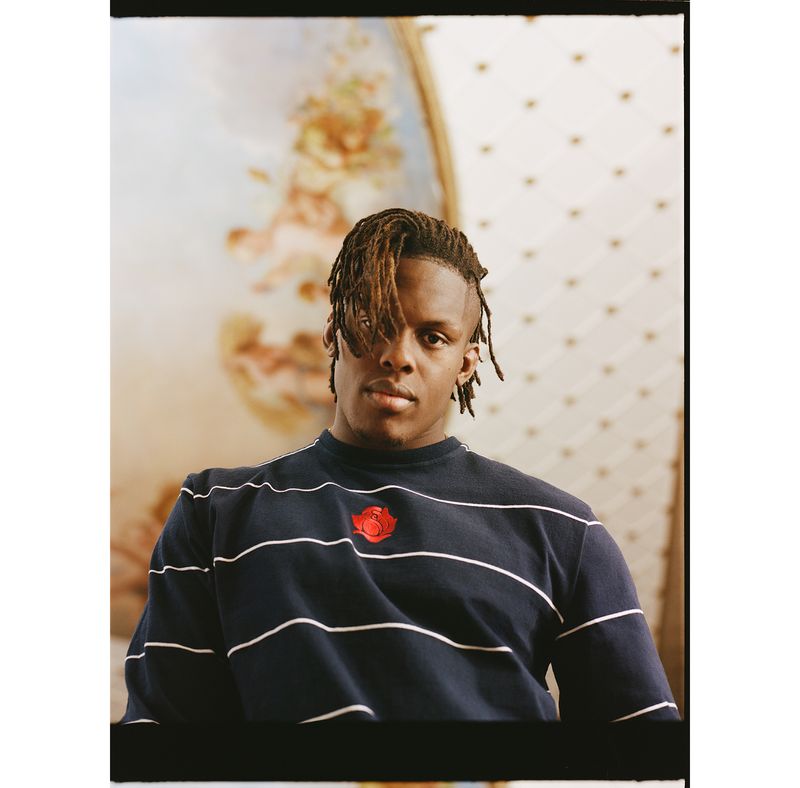

It quickly becomes apparent that the England player is more than just a physical powerhouse; he is a thoughtful, engaged and erudite individual, keen to unpick topics as wide-ranging as British politics, Nigerian family dynamics and even, at one point, the socio-economic significance of African women’s hair. Of course, he is, by any standards, not just well-educated, but broadly so. Raised in north London by Nigerian parents who taught him to value both learning and respect for his elders, he won a scholarship to elite public school Harrow before going on to study politics at London’s School of Oriental and African Studies. There was no question of him being allowed to abandon his university degree once he had made his breakthrough in senior rugby. And, in his eyes, that’s a good thing: the experience has made him well-rounded. “My sixth form and university could not have been any different,” he says of swapping the top-hat-and-tails approach of a school that has produced seven British prime ministers for the famously left-leaning atmosphere of his college environment. “I went from the right of the right to the left of the left.”

Naturally then, he has plenty to say on rugby’s ongoing class and diversity issues. England’s 31-man squad for the World Cup was the most diverse in history, with more than a third of the players from minority backgrounds. However, almost half of the party went to fee-paying schools, the country’s traditional breeding ground for the sport.

“There’s a lot of talent that’s going untapped,” says Mr Itoje. “I think the RFU [the Rugby Football Union, the sport’s governing body in England] could do a better job promoting rugby in state schools, for example... Growing up playing rugby, there were loads of times when I would be the only black person in a room. There’s no one reason for that, but I do feel that a lot of talent within not only the black community, but also the minority and ethnic communities in this country, is not being fully realised.”

Growing up playing rugby, there were loads of times when I would be the only black person in a room

The good news, he says, is things are changing. “Compared to how it was when I first got in, the academy at Saracens now is totally different. There are loads more teenagers of colour within the system, so I do think we are moving in the right direction. But if we want to get rid of the tag of rugby being a rich white man’s sport, if we truly believe rugby is supposed to be inclusive, these are the type of conversations that we need to have.”

The discussion turns to how rugby teaches respect whereas football – Mr Itoje is a devoted Arsenal fan – increasingly seems to provide an outlet for society’s prejudices. “The standard of behaviour is definitely falling and not just in football, but in wider society, and politics as well,” he says, drawing parallels between his most recent experience of attending a Premier League football match and the acrimonious 2019 general election campaign.

He describes the rise of right-wing sentiment as “a movement that’s going across the world at present,” but cautions that racism is nothing new. “It has been around probably since humans have had eyes,” he says. “It’s something that’s learned, and for a lot of people in society – through social conditioning, through what they consume on TV and have been conditioned to think about in a certain way – it has become almost unconscious. A lot of people need to try to realise the unconscious biases they have. The first step is recognising it because once you recognise it, you can make steps to try and change.”

In case it’s not clear, Mr Itoje is an inspiring speaker, something that augurs well for his rugby career, but also rugby in general. Whether talking about society as a whole, his own approach to life, or how a distinct English identity is expressed through the style of rugby its national team plays, Mr Itoje returns to the same phrase: “Doing the right thing at the right time”.

It’s a mantra that was drummed into England’s players at the World Cup, but, more importantly, one he feels confident can take them to even greater heights in the years ahead. “We have a team that’s hopefully going to stay together for a period of time now,” he says. “I think our best days can be in front of us.”

Whether the same can be said for Saracens, the reigning Premiership and European champions, is harder to tell. Mr Itoje clearly loves the club, having come through its ranks and benefitted from its investment in youth. When we meet, he seems sanguine about Sarries’ 35-point deduction as punishment for persistently breaching the annual £7m salary cap. “We all love Saracens, and I think that this situation is actually going to pull us closer together,” he says.

The club has subsequently been relegated from the Premiership after failing to comply with the cap, and questions are being asked about how the scandal might affect the unity of the national team, which includes a number of Saracens players. Mr Itoje’s verdict – “I don’t think it’s going to impact England” – will be put to the test in the upcoming Six Nations Championship. Given his track record of galvanisng those around him, England’s opponents would probably be wise not to get their hopes up.

The 2020 Six Nations Championship begins on 1 February