THE JOURNAL

An extract from the new Vintage book by Norwegian author Mr Karl Øve Knausgård .

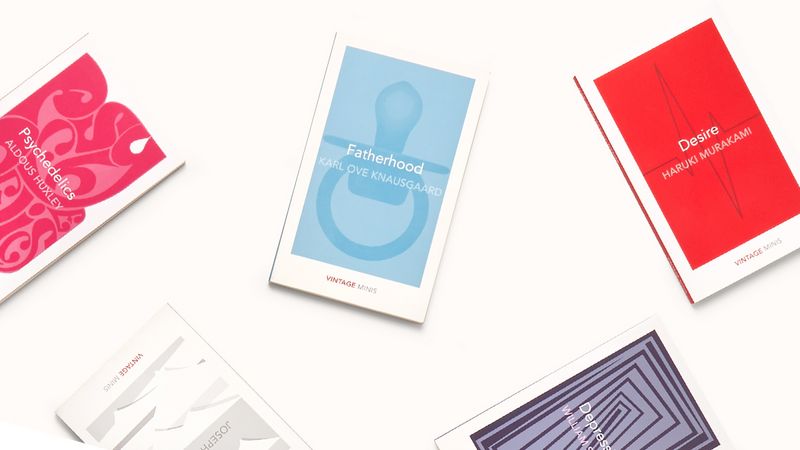

This June sees the launch of Vintage Minis, a new collection of small books designed to tackle big subjects. Each volume contains a snippet from a previously published work by one of the world’s best writers, with the 20 launch titles including Desire by Mr Haruki Murakami, Eating by Ms Nigella Lawson and Death by Mr Julian Barnes, among others.

What follows is an extract from Fatherhood by Mr Karl Øve Knausgård, which itself is an extract from A Man In Love, the second book of his six-book masterwork My Struggle. In this passage, which we’re sharing with you just in time for Father’s Day, the author reflects wistfully and with great affection upon the rapidly developing personality of his eldest child, Vanja, who would have been around five years old at the time.

I observed her. Her long, blonde hair was already over her shoulders. A small nose, a little mouth, two tiny ears, both with pointed elfin tips. Her blue eyes, which always betrayed her mood, had a slight squint, hence the glasses. At first she had been proud of them. Now they were the first thing she took off when she was angry. Perhaps because she knew it was important for us that she should wear them?

With us, her eyes were lively and cheerful, that is, if they didn’t lock and become unapproachable when she was having one of her grand bouts of fury. She was hugely dramatic and could rule the whole family with her temperament; she performed large-scale and complicated relational dramas with her toys, loved having stories read to her, but enjoyed watching films even more, and then preferably ones with characters and high drama, which she puzzled over and discussed with us, bursting with questions but also the joy of retelling. For a period it was Astrid Lindgren’s Madicken she was mad about, and this caused her to jump off the chairs and lie on the floor with her eyes closed; we had to lift her and think at first that she was dead, then realise she had fainted and had a concussion, before carrying her, with eyes closed and arms hanging down, to her bed where she was to lie for three days, preferably while we hummed the sad theme from this scene in the film. Then she leapt to her feet, ran to the chair and started all over again.

At the nursery’s Christmas party she was the only one who bowed in response to the applause and who obviously enjoyed the attention. Often the idea of something meant more to her than the thing itself, such as with sweets; she could talk about them for an entire day and look forward to them, but when the sweets were in the bowl in front of her, she barely tasted one before spitting it out. However, she didn’t learn from the experience; the next Saturday her expectations of the fantastic sweets were as high again. She wanted so much to go skating, but when we were there at the rink, with the small skates Linda’s mother had bought for her on her feet and the little ice hockey helmet on her head, she shrieked in anger at the realisation that she couldn’t keep her balance and probably wouldn’t learn to do so anytime soon. All the greater therefore was her joy at seeing that she could in fact ski, which happened once when we were on the small patch of snow in my mother’s garden trying out equipment she had come by. But then, too, the idea of skiing and the joy at being able to do it was greater than actually skiing; she could function quite happily without that.

She loved to travel with us, loved to see new places and talked about all the things that had happened for several months afterwards. But most of all she loved to play with other children, of course. It was a great experience for her when the other children at the nursery came back home with her. The first time Benjamin was due to come she went around the evening before, inspecting her toys, and was worried stiff that they were not good enough for him. She had just turned three. But when he arrived they got on like a house on fire and all prior concerns were swept up in a whirl of excitement and euphoria. Benjamin told his parents that Vanja was the nicest girl in the nursery, and when I told her that – she was sitting in bed playing with her Barbies – she reacted with a display of emotion she had never manifested before.

“Do you know what Benjamin said?” I said from the doorway.

“No,” she said, looking up at me with sudden interest.

“He said you were the nicest girl in the nursery.”

I had never seen her filled with such light. She was glowing with happiness. I knew that neither Linda nor I would be able to say anything to make her react like that, and I understood with the immediate clarity of an insight that she was not ours. Her life was utterly her own.

“What did he say?” she answered, she wanted to hear it again.

“He said you were the nicest in the nursery.”

FATHERHOOD is part of the Vintage Minis series published at £3.50. From A MAN IN LOVE by Mr Karl Øve Knausgaard. Copyright © Forgalet Oktober 2009, English translation copyright © Mr Don Bartlett 2013

Like father

Keep up to date with The Daily by signing up to our weekly email roundup. Click here to update your email preferences