THE JOURNAL

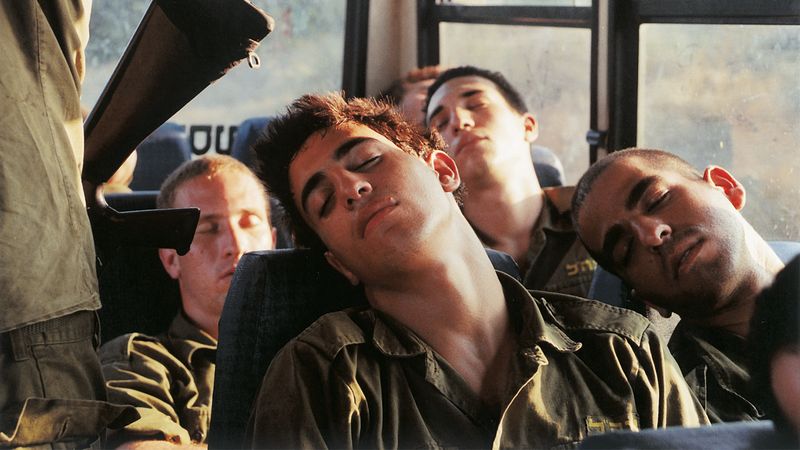

“Untitled”, from the series Soldiers, 1999. Photograph by Mr Adi Nes, courtesy of Mr Adi Nes and Praz-Delavallade Paris, Los Angeles

I once dated a man who, several drinks deep, gingerly admitted he would be disappointed to learn his prospective wife earned more money than him. My initial reaction was entirely what one might expect from a bright-eyed, slightly tipsy university student who had recently signed herself up for a Women And Power history course: unabashed fury. He wasn’t a misogynist or even a macho man, though he did have nice arms. He was a self-described feminist, so it wasn’t until I’d recovered from my bout of indignation that I took much notice of the crumpled look on his face. He was ashamed, but also confused.

All his life he’d been told, and told himself, that being a man meant, among other things, being the breadwinner. He wasn’t able to reconcile that with his belief that women should be treated the same as men or the realisation that, sometimes, the women who happen to be married to men bank a larger pay cheque than their husbands. Society’s standards might have shifted significantly since his father’s or grandfather’s day, but he couldn’t shrug off the expectations of his gender.

This incident occurred several years before anyone started shouting about what’s come to be known as a crisis of masculinity. In the spectre of a Mr Donald Trump victory, #MeToo and Ms Greta Gerwig’s Little Women being nominated in the same category as Mr Todd Phillips’ The Joker at this year’s Oscars, those contradictions and conflicts are felt even more acutely than before. “Masculinity is propped up by itself,” says Ms Alona Pardo, curator of the exhibition Masculinities: Liberation Through Photography at the Barbican in London. “It has this kind of underlying fear of its own collapse. Asserting one’s masculinity underwent a resurgence during the suffrage movement, for instance. And whenever masculinity sees itself being threatened, it rears itself quite clearly.”

The time could hardly be riper, then, for this show, a collage of more than 300 works from 56 international artists. Its breadth and scope are staggering and it includes pieces from artists who have never exhibited in the UK before. It was crucial, given the timing, says Ms Pardo, to usher in a set of fresh voices. “These are artists who are working at the cutting edge,” she says. “Really contemplating, reflecting, meditating, thinking through what gender means today.”

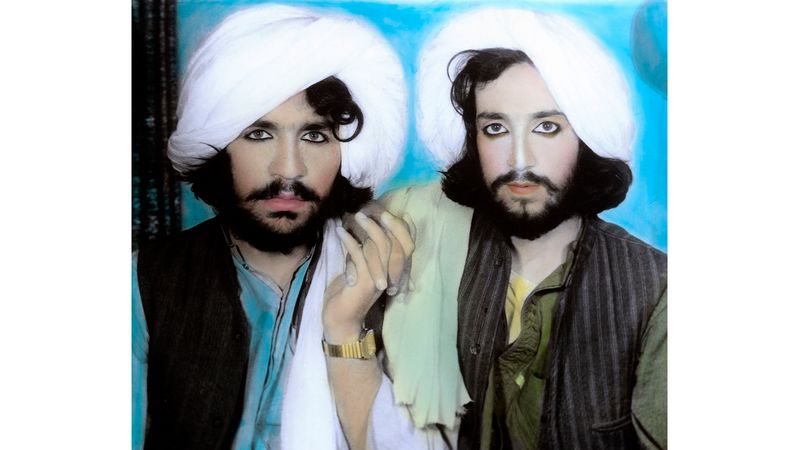

“Taliban Portrait”, Kandahar, Afghanistan, 2002. Photograph by Mr Thomas Dworzak, courtesy of Collection T Dworzak/Magnum Photos

The show borrows its main thesis from sociologist Ms RW Connell’s theory of hegemonic masculinity, which, at its root, suggests that the way we perform our gender ensures men remain dominant and women subordinate. So far, so patriarchal. But Ms Connell went further and contested that the idealisation of typically masculine values – strength, virility, power and so on – also serves to subjugate forms of masculinity that don’t fit the alpha mould.

Even the exhibition’s title, says Ms Pardo, is slightly tongue in cheek. “Of course, men don’t necessarily need liberation, but it’s only one strata of men who hold the power,” she says. “A large majority of the male population don’t hold it because they don’t fit atop the gendered hierarchy. They belong to a marginalised masculinity, a soft masculinity. They don’t conform to this kind of aggressive masculine ideal.”

The exhibition attempts to represent all forms of masculinity in six overlapping, thematic sections. The first, “Disrupting The Archetype”, deconstructs stereotypes of the male ideal and interrogates paradigms such as the cowboy, bodybuilder or soldier. The photographer Mr Adi Nes, for example, in his endeavour to expand our narrow definition of military masculinity, points a homoerotic lens on Israeli fighters at rest on a bus, but in another shot, depicts an amputee. “We’re not showing soldiers in the heat of battle,” says Ms Pardo. “What we’re showing is how they consciously perform their masculinity to the camera through these works, and how they disrupt or contradict public perceptions of the soldier.” The fact that they’re staged, using actors rather than active personnel, serves only to underline the point.

A large majority of the male population don’t hold power because they don’t fit atop the gendered hierarchy

Another segment, “Male Order”, examines power dynamics and patriarchal structures. Alongside photographer Mr Andrew Moisey’s spellbinding “The American Fraternity” (2018), an exposé of toxic masculinity in frat houses, which includes an index of brothers who went on to become American presidents, politicians and Supreme Court justices, sits Mr Richard Avedon’s The Family (1976), 69 portraits of the American political elite in a post-Watergate world. “Of course, the series is full of white men wearing suits,” says Ms Pardo. “It’s showing the confluence of power and how that power is perpetuated and propagated through a system of patronage that’s handed out by white men to other white men.”

Commenting on our current political climate is Ms Claire Strand’s hilariously snide “Men Only Tower” (2017), a precariously balanced phallus of Men Only magazines, a periodical that prided itself on the ballsy mission statement, “We don’t want women readers. We won’t have women readers.” She has hidden images of resistance inside the pages. There are 68 issues stacked in total, the number of floors Mr Trump claims Trump Tower has (it has 58). “It’s a reference to male exaggeration, but it’s also encased in a glass tower, so it’s looking at how women have been excluded from the corridors of power,” says Ms Pardo. “It invites us to think about patriarchy, gender and class.”

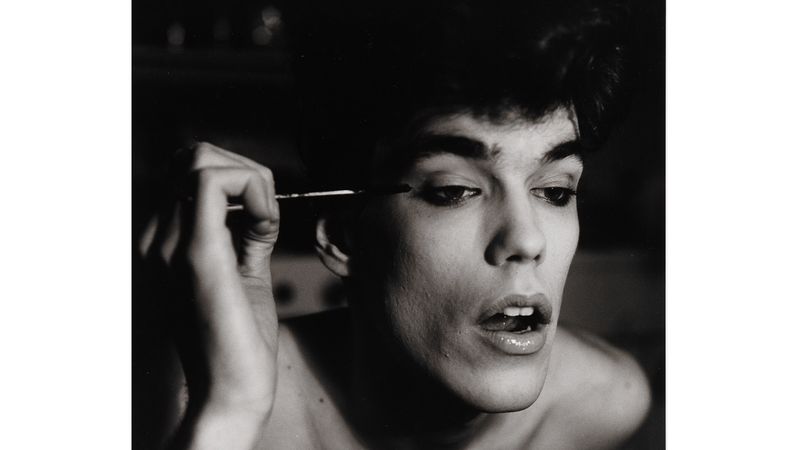

“David Brintzenhofe Applying Make-Up (II)”, 1982. Photograph by Mr Peter Hujar, 1987 The Peter Hujar Archive LLC, courtesy of Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York and Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco

Further on, fatherhood also takes the spotlight. Efforts at “recoding and reformulating the traditional family photograph”, as Ms Pardo puts it, come in the form of Mr Richard Billingham’s Ray’s A Laugh (1996) series, which paints a gloriously bleak portrait of his life growing up in Thatcher’s Britain in a high-rise in Birmingham. His unemployed, alcoholic dad is variously shown shirtless on an unkept bed, being berated by his estranged wife and, in one shot, swigging from a bottle of cider. “It casts his father as a kind of failed character, but it doesn’t condemn him,” says Ms Pardo. “It operates much more on a level of a social critique. It’s looking at how the father is seen as being a disciplinarian or authoritarian figure and how, invariably, men don’t always and can’t live up to those expectations.”

Race, too, is a pivotal theme. In “Reclaiming The Black Body”, conceptual artist Mr Hank Willis Thomas’s “Unbranded: Reflections In Black By Corporate America” (2018), distorts and manipulates adverts, revealing how black men have been commodified and commercialised from 1968, the year the Civil Rights Act was signed, to 2008, when Mr Barack Obama was elected, to demonstrate “how advertising is largely crafted by white American, predominantly male, advertisers and how that perpetuates cultural stereotypes of African-American men as hyper-sexual beings or gangsters or criminals,” says Ms Pardo.

The show’s starting point, the 1960s, was an important juncture for Ms Pardo. “The post-war period is when we have great seismic social change,” she says. “The counter-cultural movement. The civil rights struggle. The sexual liberation movement and feminism. But also, in tandem with feminism, there was virtually a kind of men’s liberation, men’s activist movement, as well. Alongside the rise of LGBTQ+ rights.”

In the section entitled “Queering Masculinity”, artists explore how their sexuality has defined their performance and experience of masculinity. Pointing to Mr David Wojnarowicz’s haunting photographs of Downtown New York piers and Mr Peter Hujar’s intimate portraits of queer expression, Ms Pardo explains that these pockets of the city were paradises from the prison of gender expectations. “They were railing against the patriarchal system that outlawed them and made them live a furtive existence,” she says. “It was an idyll, a safe space where men could express themselves.”

The nature of curation means it’s impossible to escape the air of appraisal pacing through the show, but the intention is far more celebratory than scolding. “What we don’t want to do is negate the male experience,” says Ms Pardo. “It’s not meant to be a show that men come into and leave self-loathing. The show is offering up many different ways of being. We hold men up to a very narrow definition of masculinity, but we also shackle them in. All these toxic mantras – boys don’t cry, man up – that’s a massive pressure. It’s hindering personal emancipation. It’s hindering men reaching their full potential because they’re trying to live up to something that society has dictated. And, in fact, that’s a complete fallacy.”

It might strike the visitor as curious, moving from room to room, that an exhibition of this sort and scale hasn’t been mounted before. This isn’t the first time artists have captured or critiqued the masculine condition. “The art has always been there,” says Ms Pardo. “But it goes deeper than art history. Society in general has not wanted to question the stability or the power of masculinity because once it does, its artifice is exposed. And, ultimately, that’s what I hope the show is doing.” Now we just need to take notice.

Masculinities: Liberation Through Photography_ is at the Barbican, London, until 17 May_