THE JOURNAL

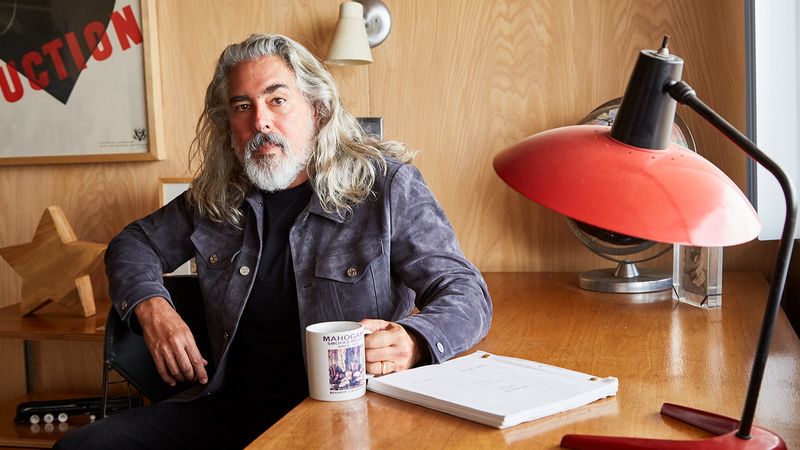

From his modernist gem of a home, the BFF of Mr Bill Murray looks out on the landscape of Hollywood legend.

Head northeast out of Los Angeles into a vast, dusty chaparral, the Mojave Desert, that windblown, sun-faded Hades. Beyond Pearblossom Highway, beyond Edwards Air Force Base, past the last of the In-N-Out Burgers, the hills to your left suddenly harden, sharpen into tectonic teeth and, to your right, the land slopes into an alluvial marsh, once the great Owens Lake – siphoned off long ago, to send water to the big city to the south. Now you are almost at the Glazer house.

“Being East Coast people, when I heard the word Mojave, I thought desert where I would die,” says Mr Mitch Glazer. “But psychologically, when you take that drive, and you hit Mojave, you’re somewhere else.” The city falls away and “everything after that feels like an adventure. And you end up somewhere lunar and extreme.” The Alabama Hills are a sensational geological anomaly which have been Hollywood’s stand-in for the exotic, from the Wild West of Mr John Wayne and Hopalong Cassidy to the Hindu Kush of Gunga Din and Tony Stark’s missile demonstration in Iron Man. Just there, huddled inconspicuously into the foothills of the Sierra Nevada in the dramatic shadow of Mount Whitney, is a house designed and built by Mr Richard Neutra in 1959. “Neutra completely got how to maximise without dominating,” says Mr Glazer. “If you look back at the house from the rocks, it’s basically invisible. But the views, through these walls of glass...” Mr Glazer remembers that same journey in 1992, when he and his wife, Ms Kelly Lynch, first made the trip to see the house on the recommendation of an estate agent. At the time, the house was owned by Ms Ruth Schaffner, heiress to the American clothiers Hart Schaffner Marx. She had run the place as an artists’ retreat, inviting the likes of Mr Ed Moses and Mr Ed Ruscha to stay for long stretches.

What had begun as a lark for Mr Glazer, “a fun day trip out of the city”, became very serious as soon as he and Ms Lynch saw the house. “As we drove in, I had that déjà vu feeling that was really kind of disorienting – oh my god, I’ve been here before,” says Mr Glazer. “And I was thinking I had, in some kind of spiritual way, but it was just being an eight-year-old kid sitting with the TV and seeing the Lone Ranger rear up in front of the rocks that I was driving by. It is the landscape of my childhood.”

They put in a bid right away and, in the 30 years they’ve owned the house, they too have treated it as a creative outpost, a retreat to which they can escape the city (where they live in an equally exquisite house designed by Mr John Lautner). It was here, for example, that Mr Glazer, a screenwriter, producer and director, wrote much of his show Magic City, in which he channelled the Miami Beach of the 1950s.

“This house is remarkably like the house I grew up in from the mid-1950s,” he says, “a post-and-beam house inspired by Mies van der Rohe and European modernist aesthetics, on Hibiscus Island, on the beach, which had nothing to do with the other homes around it.” Mr Glazer’s father was a lighting designer and electrical engineer who turned on the glitz at the Fontainebleau, Eden Roc, Deauville and Carillon hotels in Miami Beach and clearly passed down some of his enthusiasm for the era’s design to his son, who has preserved his High Sierra treasure like a gemstone.

Very little in Mr Glazer’s house has been changed in the 60 years since it was built. The original canary-yellow laminate still covers the guest bathroom sink. The fascias on all the built-in cupboards are the same. Drawings by Mr Glazer and Ms Lynch’s daughter, now a television writer, dot the kitchen walls. “The amazing thing about this home is, when you try to put things in it. This house rejects things outright,” says Mr Glazer.

“I think it's more American to keep redecorating everything all the time,” says Ms Lynch. “And I always felt we were more European in our approach to getting things that are beautiful, that are timeless. Our life keeps changing and we keep changing. We keep doing stuff and travelling and writing and acting and, whatever we’re doing, what happens outside keeps changing, but these places are like our cribs. They sort of hang in there like, we did it.”

Outside it is completely wild. Old testament wild. Hesiod wild. And, as big and beautiful as these rocks are, they also feel perilous. Even the one in the front garden, which was dynamited out for a swimming pool, makes the idea of raising a child here, at least part of the time, a bit of a hair-raising proposition. “Well, it’s absolutely hysterical,” says Mr Glazer of trying to keep an eye on his daughter while she was growing up here. “I was such a nervous parent, wrapping her in protection. We have photos of her climbing those rocks with a helmet and skateboard pads and finally she just went, ‘Oh, fuck it.’ But this place was just fuel for her. It was a great dream place.”

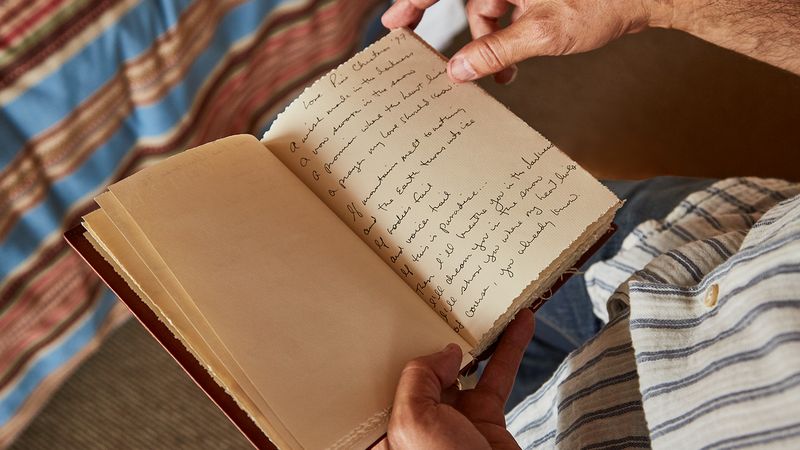

Mr Glazer has also used the place to dream his big screen dreams, since adapting Mr Charles Dickens’ Great Expectations here in the mid-1990s. In the film, Mr Ethan Hawke plays Finn as a literary boy from the sticks of Florida, not unlike Mr Glazer himself. After studying English at NYU, Mr Glazer started writing for magazines. “It was great to be in New York in the magazine business as a writer in the 1970s,” he says. “I was just like a sponge and it was all doors open and access was there.” He soon started editing the magazine Crawdaddy, where he was the first to write a cover story on Mr John Belushi. “Which turned out well, thank God. And I’m going to bring it to John at his apartment on Bleecker Street. We’re going to dinner that night. I knock on the door and Hunter Thompson opens the door. This is in 1977. I’m a huge fan and there’s Hunter, Fear And Loathing Hunter. And I said, ‘Is John here?’ And he said, ‘Sure. Do you have the article? John wants me to read it.’ And I went, ‘Oh, no’. John’s screaming, ‘Give it to Hunter.’ And I go, ‘OK.’ I was 23, 24. And I give him the story, and he’s sitting there in front of me, and I’m thinking this could go really bad. I mean, John and I were already friends, but this is an endorsement that would have meant something to John. So Hunter reads it and he puts it down and looks at me and says, ‘It’s like chopping wood.’ And I said, ‘It is.’ Not knowing exactly what he was talking about. He said, ‘Writing.’ And then instantly we were both writer guys, peers. And John comes out of the shower and Hunter says, ‘This guy has a wonderful work of literature here. Stay close to this man.’ And then we spent the rest of the night together and of course I can’t remember it at all.”

Mr Glazer’s next move was into film. “And the way into movies for me was sitting in John Belushi’s apartment, which Danny Aykroyd called the Reich Palace, because it was the first apartment that was kind of grand. And it was probably like $600 a month or something. We're sitting in the living room and John’s on the phone with Universal. He says, ‘So for Kingpin, why don’t you just have Mitch write it?’ He and Danny had an idea for a film about pot smugglers to be called Kingpin, which never got made obviously, but post-Animal House, he could have whatever he wanted and that’s what he wanted. And he says, ‘OK, great, so Mitch is going to write it,’ and hangs up. And he literally changed my life from magazine writer to screenwriter in real time.”

Mr Glazer’s life has continued to change, to be more entrepreneurial in Hollywood. “I have a bunch of things going, all of which I really like, happening simultaneously,” he says. As he speaks, sitting on the sofa in the living room, threads of lightning lash Mount Whitney behind him. “So it’s a little bit like that Ed Sullivan Show plate-spinning routine. You just go back to the pole and spin it and then the plate keeps going and then you move on to the next, until one of them takes control.”

Mr Glazer and Ms Lynch met in 1989 through the agent Ms Sue Mengers. Their first date was the premiere of Ms Lynch’s breakout film Drugstore Cowboy. Between them they have a crowd of incredible friends whose names litter the guestbook here. Mr Glazer says he takes great solace in the exchange he has with his pals, including Mr Graydon Carter and Mr Bill Murray, with whom he regularly works. “You look for those people,” he says. “Helmut Newton was one. To the day he died, he was Helmut. I asked Helmut at one point, what the key was. Is there a way to stay true to yourself as you age and navigate the world? And he humoured me, thank God. He said, ‘Make them pay you. Always make them pay you. The second you lose the mercenary connection with the world, you disengage in a way that ages you.’ He was dead serious. ‘Mitch,’ he said, ‘I'll shoot bar mitzvahs, I’d shoot anything, as long as it was transactional.’”

Nestled into these ancient boulders, the worlds of Hollywood, of commerce and transaction feel a million miles away. Mr Glazer and Ms Lynch say they feel a profound connection to the place, enough to create their own stories here, weave their own mythologies. Just there, beyond the big round boulder into which their daughter placed a table and chairs and held Alice In Wonderland tea parties between two vertical rocks, Mr Glazer scattered the ashes of his parents, who felt as at home here as anywhere. “We’re not the first people who think that would be a great place to have ancestors buried,” he says. “People in town who are into that stuff say the original people here were drawn to these iconic and sacred-looking rocks there. I’m sure there were ceremonies held there.”

And why not, you think, as it all begins to shrink in the rearview. That place feels bigger, more dramatic than the mundane world to which you are returning – higher maybe, primordial, closer to myth.