THE JOURNAL

Watched by Mr Charles Pélissier, French cyclist Mr Amédée Fournier takes a rest during the 11th stage of the Tour de France, 1939. Photograph by Spaarnestad Photo/Mary Evans Picture Library

In 2014, Mr Ji Cheng of the Giant-Shimano team joined a select group of riders to be awarded the lanterne rouge – the unofficial prize bestowed by fans on the man who comes in last on the Tour de France. Mr Cheng crashed on the Champs Élysées and completed the final stage of the 3,500km race injured, on his own, and far behind all other competitors. However, by completing the world’s greatest cycle race, he did more than any of his countrymen ever have: he was the first Chinese rider to finish the Tour. A victory of sorts.

The lanterne rouge takes its name from the red lantern that used to hang on the back of trains, which showed conductors that the train was complete and no carriages had become disconnected. The Tour de France is a complex and many-headed beast, and for the 200 or so men in the race, the distinction between winning and losing is not always black and white. For every man with his eyes on the prize, there are several, such as Mr Cheng, who are team players, working for the greater glory, whose job isn’t even to think about winning. And the actions of many of the lanterne rouge winners prove that coming last in style is a victory in itself.

So, while most of the world gets ready to watch the contest for who will win the yellow jersey over the next few weeks, let’s take a moment to revisit the memorable ways some of the greatest lanterne rouge recipients succeeded in finishing last.

The start of the first Tour de France in Paris, 1903. Photograph by Schirner/Ullstein Bild via Getty Images

Mr Arsène Millocheau of Chartres, France, was the first last man, bringing up the tail of the inaugural Tour in 1903. Mr Maurice Garin, the first winner, sometimes arrived at the stage finishes before the timekeepers but Mr Millocheau’s name didn’t feature in the official results for some stages because the paper had to go to press before he crossed the line. Maybe his rudimentary equipment failed him – history doesn’t record why – but he ended up finishing nearly 65 hours behind Mr Garin. Nevertheless, Mr Millochau was a cycling pioneer, taking part in the first Paris-Roubaix and was still riding his bike at the age of 81 – slow but steady into his ninth decade.

Mr Amédée Fournier prepares to set off on the Stage Two time trial, 1939. Photograph by Offside/L’Equipe

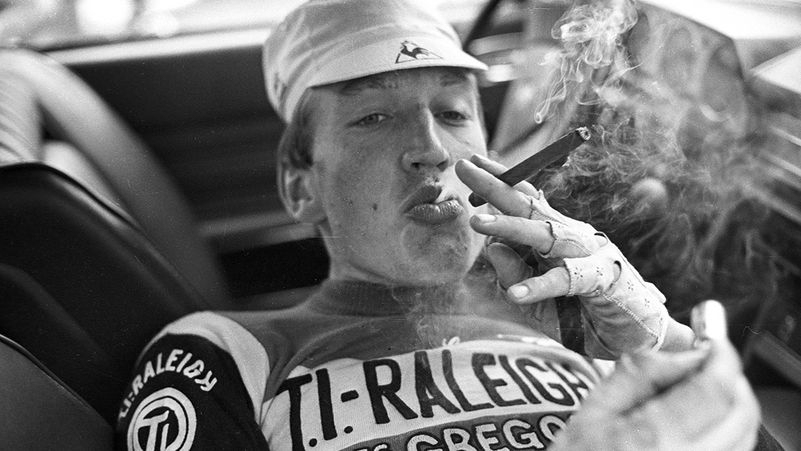

The young Frenchman Mr Amédée Fournier made a sensational impact on the 1939 Tour, winning two early stages and briefly wearing the yellow jersey. But the sprinter had never, he confessed before the race, ridden up a proper mountain. “Climbing is a bit of a grind, I don’t like it much,” he added. Mr Fournier was good on the flats, but couldn’t hack climbs like the fearsome 2,115m Col du Tourmalet. Mr Fournier lost time on the hills, lost time after getting sick from eating bad grapes, and even by taking a nap in a field. He was in the lanterne rouge position for most of the race, and risked elimination more than once.

Mr Aad van den Hoek during the Tour de France, 1978. Photograph by Cor Vos

When the Dutch star Mr Hennie Kuiper crashed out of the 1976 Tour, while descending a mountain in a storm, it left his team without a captain and his teammates, who had been ready to give their all towards his victory, without a goal. So Mr Aad van den Hoek, a talented young domestique (as the supporting riders are known), decided to shoot for last place. From the 1950s to the 1970s in particular, it could be a lucrative place to be. The lanterne rouge was so popular with fans that the last-placed man would be invited to all the post-Tour city-centre races and could make double his salary in appearance fees in just a few weeks. So Mr van den Hoek’s new aim was to finish bottom: he hid behind a car and let the peloton keep going, losing precious minutes that would guarantee him last place.

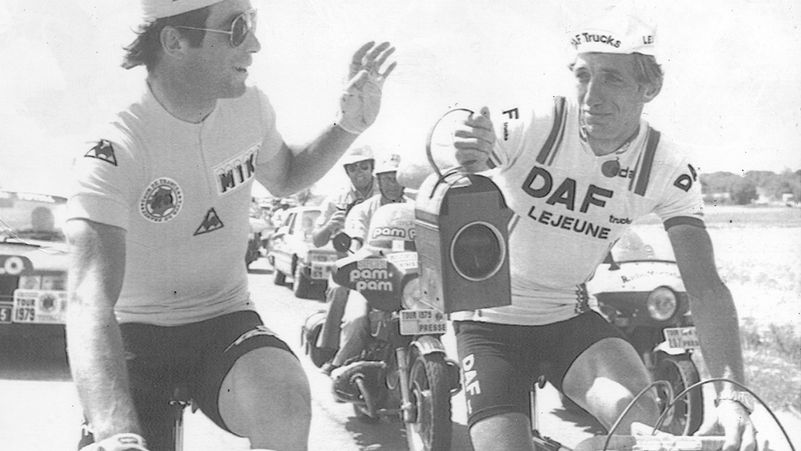

Overall leader Mr Bernard Hinault hands over the red lantern to Mr Gerhard Schönbacher for taking last place, 1979. Photograph by Ullstein Bild/Topfoto

In 1979, Mr Gerhard Schönbacher was a young Austrian sprinter riding for a little-known team, DAF Trucks. At the race’s first rest day, the sponsor visited and complained that his company wasn’t getting enough publicity. Mr Schönbacher, clever fellow, knew the yellow jersey wasn’t the only way to get into the papers. He went for the lanterne rouge, playing up his campaign by telling the journalists he wanted to come last. On the final stage, surrounded by cameras, he got off his bike on the Champs Élysées and kissed the finish line. This infuriated the organisers, who didn’t like people racing for last place. In 1980, they instigated a rule that eliminated the last rider after a number of stages. Despite these new regulations, Mr Schönbacher showed genuine finesse to stay just above the elimination places and then fall back at the end to take his second lanterne rouge.

Messrs Lance Armstrong (left) and Jacky Durand during the final stage of the race, 1999. Photograph by Mr Gero Breloer/DPA/Press Association Images

In 1990, Mr Jacky Durand was one of the darlings of French cycling. He was famed for his attacking style and his willingness to test his luck in daring breakaways with only the tiniest chances of success. In 1999, Mr Durand was caught in a crash; then, when swapping his damaged bike for a new one, his brakes failed, he fell again and another team’s car almost ran right over his leg. Somehow, he completed the stage and, despite terrible injuries, did not abandon the race. “Every year I’ve raced the Tour, I’ve always attacked,” he told the papers. “This year, because of my crash, I’ve attacked, but only backwards.” As the Tour went on, things improved and Mr Durand got up to his old tricks again, which led to him – the lanterne rouge – standing on the podium on the Champs Élysées, proud recipient of the Prix de la Combativité (the most aggressive rider prize). It was the ultimate triumph of the underdog.

Messrs Robbie McEwen (left) and Wim Vansevenant on the Tour, 2007. Photograph by Cor Vos

Perhaps the greatest lanterne rouge champion is Mr Wim Vansevenant, a Belgian who was the last-placed man three times from 2006 to 2008. He spent his career in the service of his teams’ star riders – in his lanterne rouge years, Messrs Robbie McEwen and Cadel Evans. He would fetch them water, fend off attacks from opposing teams and set them up for the sprint finishes. Mr Vansevenant knew that once his job in a stage was done, he had to sit up and rest his legs, because he’d have to do the same the next day (and the one after that…).

In those three years, the Belgium team won the green jersey (the jersey awarded for most points), had one second and one third place on the overall podium, and enjoyed multiple stage victories – thanks, in no small part, to Mr Vansevenant and his lesser-known teammates, and their willingness to sacrifice their own chances and dedicate their efforts to someone else.