THE JOURNAL

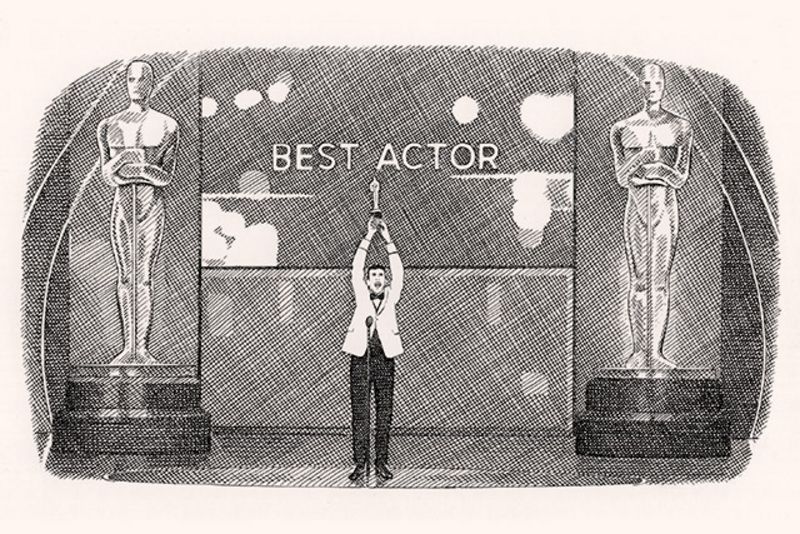

Prepare for your podium appearance (be it real or imaginary) with these lessons from the great (and the regrettable) Academy Award acceptance speeches.

The cliché that it’s a pleasure just to get nominated for any award is just that – a cliché. In reality, it’s much better to actually win. But that doesn’t mean that winning doesn’t come with its own set of stresses and anxiety – every winner has to give the high-stakes acceptance speech, a fact that really comes into focus as we gear up for that most illustrious of awards ceremonies – the Oscars. The weird thing about the Oscars speech – a crucial 45-second moment that can bring the world to a star’s feet or ostracise them forever – is that the accolade has already been given, but the fumbling on stage (or the spontaneous F-bomb that Ms Melissa Leo detonated in 2011) is what people are going to remember. Not the acting, directing, producing, hair styling, or sound mixing (whatever that is) that got the person to the stage in the first place.

Nonetheless – though there’s something farcical about the Oscars speech – your regular mortal can learn a lot from stars’ successes and failures. An acceptance speech needs to be memorable, and for the right reasons – this is true if you’re accepting an Academy Award or the Salesman of the Year trophy at your local corporate boondoggle. You don’t want your half-minute of glory to be immortalised by a streaker, as happened to Mr David Niven at the 46th Academy Awards in 1974. You want it to be like Mr Tom Hanks giving his speech for Philadelphia, in which, though he inadvertently outed his high school drama teacher, he didn’t leave a dry eye in the place. Here are some tips and tricks from watching years of good, bad and very ugly speeches, as well as some advice from professionals and those who have actually been there, on what to do when – lucky you – the big day arrives.

1. Get emotional, baby

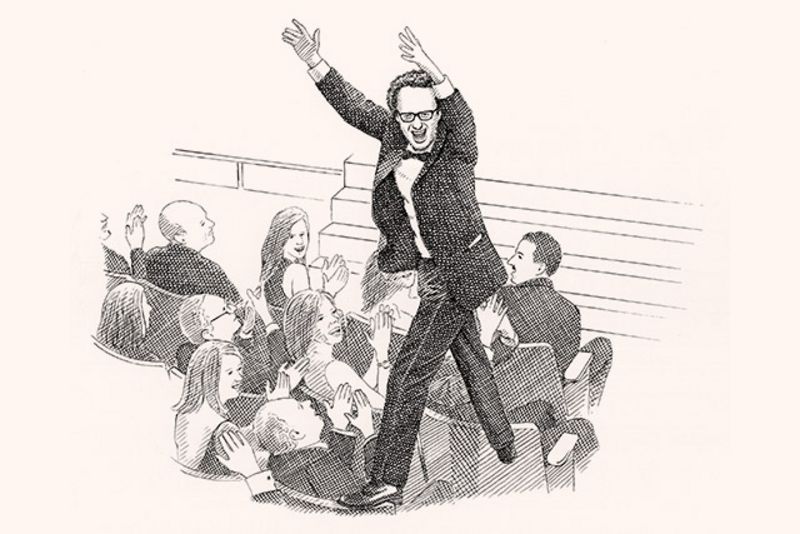

All of the best Oscars speeches, and the ones we still talk about today, are the ones where the winner (usually actors, because, let’s face it, they’re the most recognisable and prettiest faces) is really having a very emotional moment. Think about Ms Sally Field in 1971 with her oft-misquoted “you like me, right now, you like me”. Or Mr Jack Palance, in 1991, doing one-armed push-ups and talking about his start in the movie business. Those are some great speeches. “In the heat of the moment all those emotions take over and I think that’s beautiful. You shouldn’t control the emotions,” says Mr Joseph Pearlman, owner of the Pearlman Acting Academy, who coaches actors on how to give the best presentations at the Oscars, Emmys, and other awards shows. So feel free to let rip. However, on the flipside, don’t try to make it happen if it’s not there. “By far, in my opinion, the most important quality with every speech is authenticity,” says Mr Richard Greene, a communications strategist who has worked with stars and leaders including Mr Will Smith and Ms Naomi Campbell. “Authenticity is one of those things like being pregnant,” he continues. “You either are or you aren’t.” According to Mr Greene, rehearsing too much or planning out gestures will make a speech seem fake or forced. Ms Field’s heartfelt outburst is one thing, but Ms Anne Hathaway’s hardly spontaneous but nonetheless quavering “It came true!” of 2013 is another. You should also be wary of overdoing it, like Italian actor and director Mr Roberto Benigni jumping up on the seats in 1999. He looked as if he was trying way too hard. Have you heard about him making any other movies lately? Yeah, exactly.

2. Don’t be too funny

It’s classic public speaking advice to start off with a joke, but that might not be the right sentiment for every occasion. “The challenge is there are people who think they’re funny but they’re not funny,” says Mr Wynton Hall, a ghostwriter and speechwriter who works with a range of celebrity and sports clients. “When someone tries to be funny and isn’t, people see that as being glib or ungrateful. That’s an unfortunate boomerang effect.” In 2012, an anarchic Mr Jim Rash, who shared an Oscar for writing the screenplay for The Descendants, propped his statue on his leg to mock Ms Angelina Jolie’s stance on the red carpet. It was topical and on point (plus, he had the internet on his side). But, oh, how wrong that could have gone. You need to be more careful. However, says Mr Hall, for those absolutely assured of their comedy credentials, one joke that’s sure to be a rib-cracker can be a good idea. Check out veteran actress and screenwriter Ms Ruth Gordon’s speech for her 1969 win for Rosemary’s Baby. She finishes her curt speech with “Thanks all of you who voted for me.” Then, with a shrug – “For all of you who didn’t, please excuse me.” It’s sharp, unexpected and self-deprecating, perfect in its impact and efficiency – granted, this is no mean feat.

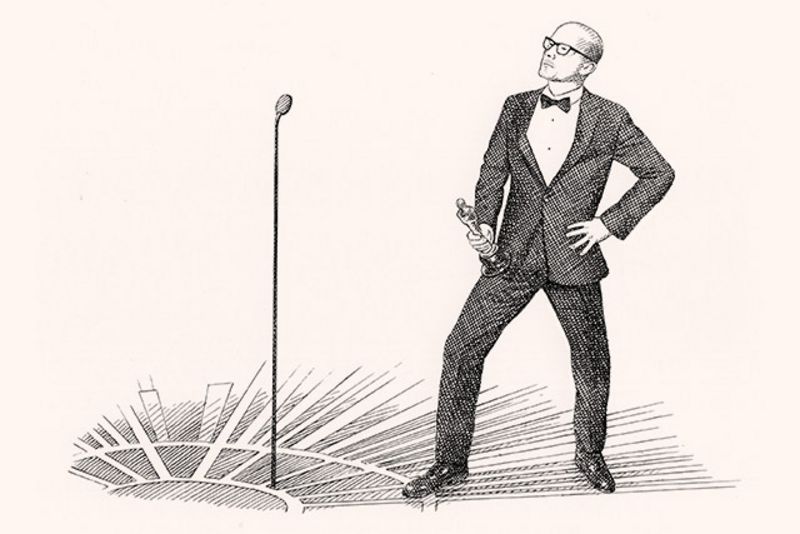

3. Size matters

The Gettysburg Address – a speech so excellent it is still memorised in grade schools – is only 272 words long. If that’s good enough for President Abraham Lincoln trying to preserve the Union, then it is certainly good enough for whatever your purposes are. The Oscar speakers only get 45 seconds, but anything over two minutes in any circumstance is far too long. “The average person speaks 150 words a minute, so when I’m crafting a speech I try to keep it to about 300 words,” says Mr Hall. He also advises people that are nervous about going over the time limit to write out the bullet points that need to be addressed and to ad lib the speech from there rather than memorising it word for word. This naturally condenses the words spoken, and gives them a more conversational tone. At the Oscars, of course, if you take too long, the orchestra starts up with some sinister music (in 2013, somewhat ridiculously, this was the theme from Jaws). If the worst happens and you do go over, deal with this (or however else they’re trying to shoo you offstage) with exuberance rather than acquiescence, taking your cue from the winning, overwhelming excitement of actors such as Mr Cuba Gooding Jr (1997: fist-pumping, shouting, jumping, standing ovation, natch) or Messrs Matt Damon and Ben Affleck (same year, shouting, more pointing and Affleck, breathily: “There’s no way we’re doing this in 20 seconds!”).

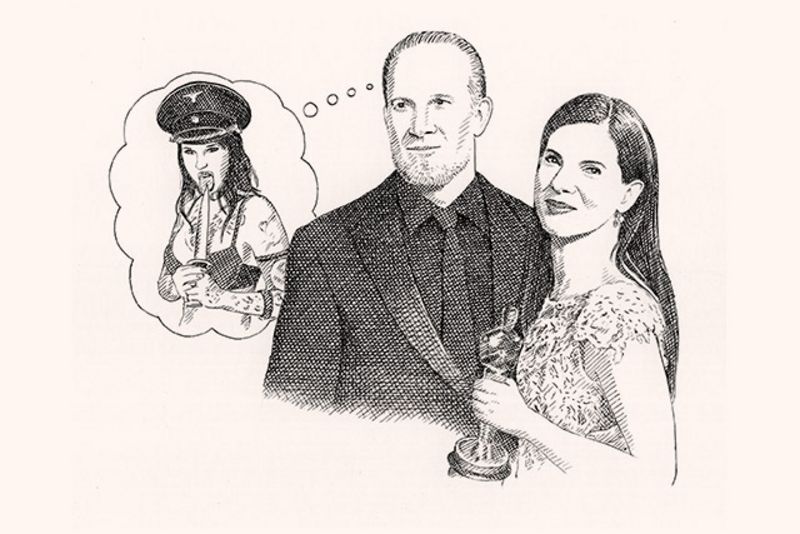

4. Many, many thanks

No one is going to say that Ms Hilary Swank’s marriage to Mr Chad Lowe ended because she didn’t thank him in her acceptance speech. But end it did. Ms Sandra Bullock didn’t thank hers and he cheated on her with a bunch of women, dressed like a Nazi, and humiliated her on a national level. OK, these speeches were probably symptomatic of marital strife, not causes in themselves. But the case remains that your “Thank yous”, though much dreaded by your audiences, are an integral part of the well-crafted acceptance speech, and you have to get them right. So just how many people should you thank? “Have a punch list of the three to five people you really want to mention here, and express how they were essential to making the achievement possible,” Mr Hall suggests. “Having that humility and classiness about yourself is the way you want to put that out there.” Think carefully about who they are though, because thanking different kinds of people affords you different qualities in the eyes of the ever put-upon audience. Thank your family if you want to seem humble. Thank members of your team if you want to seem grounded. Thank a mentor if you want to seem wise. Thank your superior if you want to seem grateful. Just for luck, thank Ms Meryl Streep – the most-thanked actress in Oscar history – because even though you may not know it, she probably had something to do with your success.

5. Stay in the moment

We grow up having watched tons of expert oration, especially when it comes from movie stars accepting trophies on television. Sure, you want to be them, but don’t let your pursuit of excellence stun you into silence. You may not know this but every year the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences sends out an acceptance speech DVD to each Oscar nominee. It’s supposed to help them prepare for the fact they might win. But it didn’t have the desired effect on Mr Iain Canning, who, as one of the producers who won a Best Picture Oscar for The King’s Speech in 2011, was in a special kind of pickle. “We made a film about giving speeches, so it was important that if the miracle happened and we won that we at least provided something thanking the right people,” he says. Alas, the DVD got to him: “It’s got these clips of everyone giving these incredible speeches” he says. “It’s quite daunting.” In fact, when the moment finally came, Mr Canning was still thinking about the DVD, specifically, about the disappearing triangle graphic it contains to help nominees visualise the 45 seconds they have to speak. Which reminded him mostly not of his own gratefulness, but of Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. Luckily, he shook himself out of it, but this should act as a cautionary lesson to all award-accepters out there: approach the podium with a clear head and keep your eyes on the prize.

What Not to Do When Accepting an Award

Do not pull out a piece of paper

Mr Derek Jeter doesn’t get up to the plate and put the ball on a tee, does he? You’re a professional; act as if you know what you’re doing. And, God forbid, if you do get out the paper, don’t put on the reading glasses, too!

Don’t get political

Ms Vanessa Redgrave came under fire for bringing up Palestinian politics in her 1977 speech and Mr Michael Moore used his win to criticise the Bush administration and he got himself booed. Booed!

Don’t be absent

Unless there is some sort of family emergency or physical ailment that is keeping you hospitalised, you should show up. Ms Joan Crawford didn’t and then they made Mommie Dearest about her. Connected? Maybe.

Don’t send a stand-in

If you’ve got the chops of Mr Marlon Brando in The Godfather then by all means send a Native American in your stead to draw attention to their plight. But the chance is, you don’t. So start a petition on Change.org or something – and accept your own award, for goodness sake.

Don’t be surprised

You have a one-in-five shot of winning. Many winners have been the favourite for months. Don’t go up there and let the first words out of your mouth be, “I’m so surprised.” Because no one else is.

Mr Brian Moylan is a writer and pop culture expert who has been covering Hollywood for more than a decade. His work has appeared in The Guardian_,_ Time_,_ VICE_,_ New York magazine and Details_, and he is a former staff writer at Gawker. He has an honorary PhD in Jersey Shore studies from the University of Chicago._

Illustrations by Mr Nick Hardcastle