THE JOURNAL

Throughout our meal at the restaurant Kiki’s, people continually greet Mr Colin McElroy. The Australian host. A blonde French woman in a khaki jumpsuit. Even Kiki, the proprietor of the spot, offers him her well wishes. McElroy lives in the neighbourhood and, if you didn’t know any better, you’d think he was one of those people born and raised on the Lower East Side, someone who hasn’t left the island of Manhattan in many moons. He’s effortlessly cool, with tattoos and a grizzled voice, and is wearing a T-shirt commemorating the spreading of Mr Jerry Garcia’s ashes. A painter by trade, McElroy works as an assistant to the artist Mr Nate Lowman.

As comfortable as McElroy may be in the city, holding court with a plate of moussaka at Kiki’s, he’d much rather be fishing. He’s a nature boy at heart, a California native, and when the pandemic began, he hit the road, camping and fishing across the western US. He had nowhere to be, so he gravitated towards the river.

When he returned to the city, he found himself pulled to the water. Most nights, after work, he’d drive out to Jamaica Bay, near John F Kennedy airport, with planes landing overhead every minute or two, go fishing.

McElroy enjoys the freedom he has as a single man to indulge in fishing, whereas his friend Mr Mac Huelster, a married father of two, doesn’t quite have the same flexibility to wade out into the water and wait. Huelster, a tall and handsome Minnesotan turned longtime New Yorker, is an in-demand stylist. A few weeks before our Kiki’s dinner, he dressed Mr Leon Bridges in a fringed baby blue BODE jacket for the Met Gala.

In a purple sweatshirt and a baseball cap, Huelster himself looks more like a skater than a stylist. He says that earlier in his career, he’d be confused for a delivery person when he showed up on set. He has reverence for the excitement of his life in fashion, but speaks of his past as something of a distant memory. Now sober, he avoids crowds and says he rarely goes out. He’s not uncomfortable at Kiki’s, but he doesn’t thrive off the scene in the same way McElroy does.

The two are quite different. They say they have a common sense of aesthetics, and a shared love of tattoos, but their connection is about the escapism fly fishing provides.

McElroy was taught to fish by his grandfather; Huelster learned from McElroy. Their loosely student-teacher relationship gives each a purpose when wading in the water.

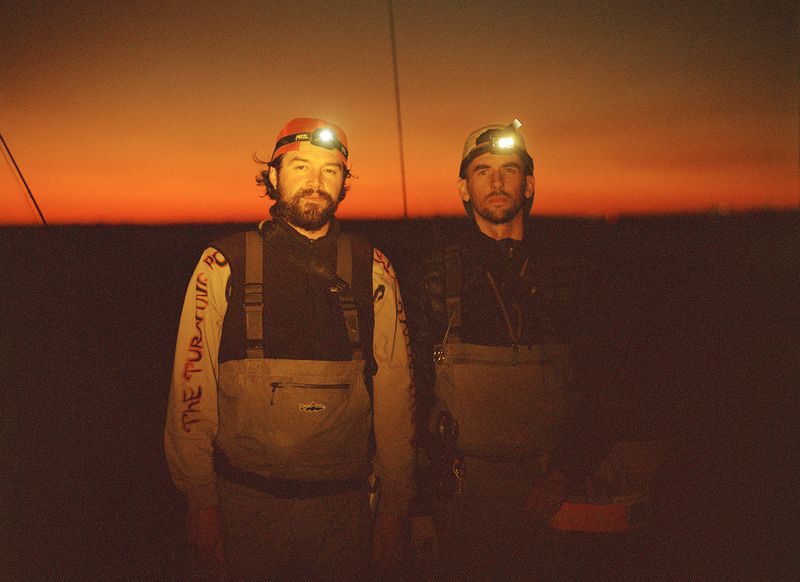

As the chaos of the pandemic settled down, McElroy returned to the city and reunited with Huelster, whom he began taking out to Jamaica Bay, where we photographed them for our Go Out series. Sitting on a bench on Allen Street after dinner, they take turns explaining the mechanics of spin fishing versus fly fishing. Huelster sounds like he’s describing a Marvel movie versus an art film.

With traditional reels, where you cast out and attempt to hook fish, the lures, he says, are “vibrating, they’re flashy and they’re making noise”. In fly fishing, where you attempt to trick fish into eating your make-believe bugs, “the Zen of it all comes through”. “It’s peaceful and everything’s kind of slower and you’re just trying to be perfect,” says Huelster.

But you can’t try too hard. “If you think about it too much and you let it get to you and your confidence level isn’t high, you don’t catch fish,” says McElroy. “If you're happy and you’re confident, you end up catching fish. It’s how the world spiritually works.”

Huelster and McElroy agree that fishing is a hobby, maybe a sport, but they talk about it with reverence, like they’ve discovered a holy combination of meditation, yoga, boxing and therapy. Fishing with friends means you’re both participating and rooting from the sidelines. McElroy, who seems to have caught enough fish for several lifetimes, says he gets more pleasure out of seeing Huelster succeed.

Occasionally they strike gold and both snare a fish at the same time. McElroy’s joy at this, which he calls “doubling up”, is infectious and sweet. “When you’re hooked up with your homie at the same time, you both have a fish on, that’s just what it’s all about,” he says.

He may be talking about fishing, but it has the quality of an infectious sermon from a pastor eager for his flock to get out there and live. It’s easy to see why Huelster is drawn to the sport when seen through McElroy’s eyes.

Their relationship is not just one way. When I ask them what they talk about in the water, McElroy brings up something he says they haven’t discussed, which is his admiration for Huelster. “I look up to him,” he says. “That’s what I’ve thought about when we go fishing. I get to hang out with this cool dude who’s very, like, dialled in with what he does.”

Huelster, more practical if no less appreciative, says, “It’s rare that I become friends as an adult.”

Then he puts their relationship in fishing terms. “Sometimes you’re driving past the ocean and you’re like, ‘Oh, there’s a jetty. I bet there’s fish out there.’ It's like we have the same brain. I haven’t had that in so long.”