THE JOURNAL

Film by Mr Sam Finney, additional surf cinematogrphy by Clem McInerney

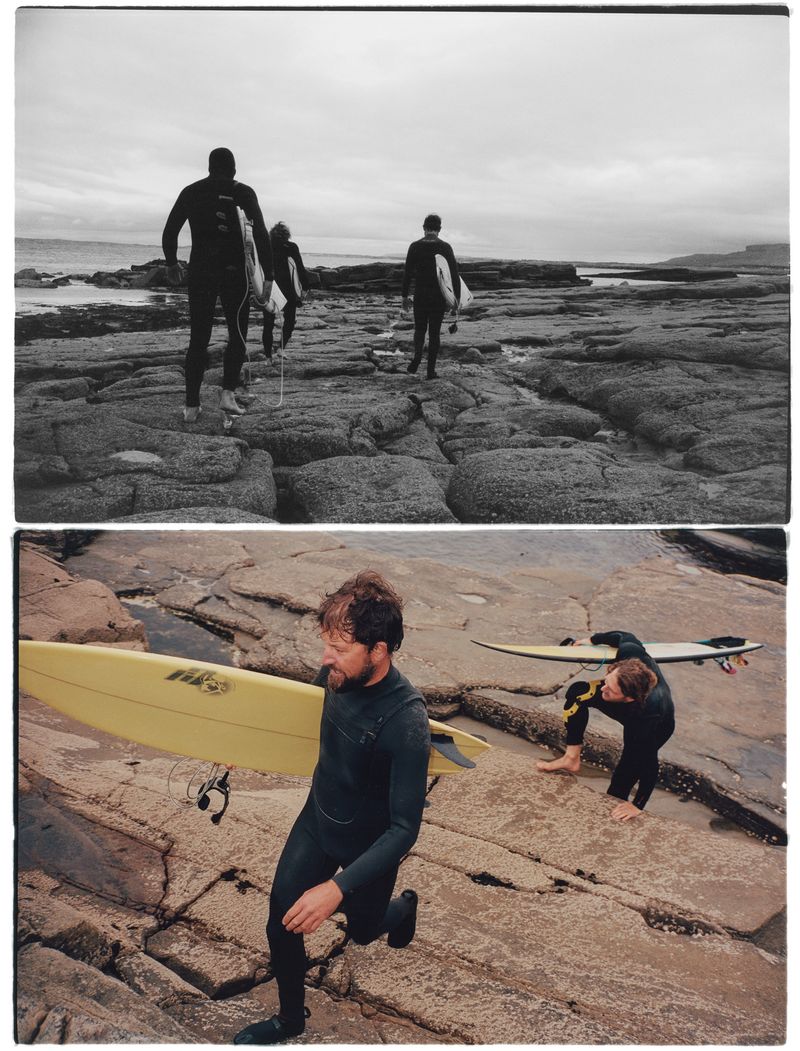

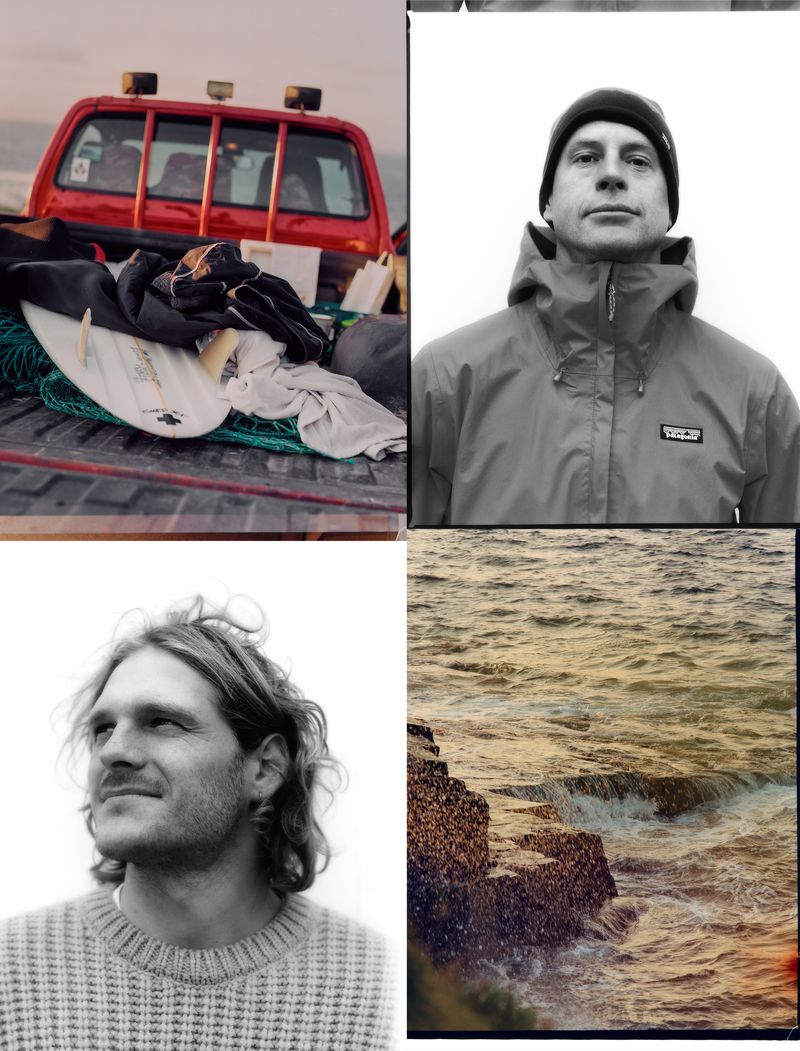

Messrs Barry Mottershead, Dylan Stott and Taz Knight have gathered at Mottershead’s cottage on Mullaghmore headland in County Sligo on the northwest coast of Ireland to go surfing. Two hundred yards down the baize hill and over the jagged sea cliffs, the wind-buffeted and wave-riddled Atlantic Ocean spreads out endlessly.

If you were to take one of the surfboards Knight is examining and paddle out to the next land mass, you would have to travel 2,000 miles west to Newfoundland, Canada. Behind the cottage, just above the nearest of the endless green hills that roll towards the foothills of Benbulbin (known as Ireland’s Table Mountain), you can see the sandstone of the central tower and turret of Classiebawn Castle.

“This house might be the best place on Earth to live,” says Stott as he takes in the view, his New York accent still strong despite two decades in this part of the world. “In winter, though, it might be the worst.”

Mottershead, a wiry, bearded South African, laughs in agreement. Outside, the watery September sun is illuminating the thick, white walls of the cottage, but the sea breeze is rattling the traditional single-glazed windows. The house is in an exposed location on one of the most exposed coasts in Europe.

“It’s funny, we are all miles away from our homes, but we couldn’t feel more at home,” says Mottershead in his still-clipped Cape Town intonation. “We have all travelled across the earth to find something and we’ve found it, and now we are hanging on to it with our claws.”

Stott, 44, and Mottershead, 39, arrived separately in the sleepy surf and tourist town of Bundoran around the turn of the millennium. Stott was a keen surfer from New York, who had spent the latter part of his teenage years and early twenties living on Hawaii’s North Shore of Oahu.

“You could surf waves that no one had surfed before. We felt like astronauts”

In 1999, after watching the surf movie Litmus, one of the first to show the waves of Ireland, he promised to visit. When his uncle opened a Xerox shop in Dublin – a late-1990s timestamp if there ever was one – he saw his opportunity and left the warmth of Sunset Beach, eventually making it to Bundoran.

Amazed by the quality of the waves and the hospitality of the small crew of local surfers, he vowed to return, and did so five years later, in 2004. That three-week trip turned into a three-month stay. He also met a local girl, now his wife and mother of their five-year-old surf-mad son. He decided to sell his tree surgeon business in New York and head back to Ireland permanently.

He enrolled at University College Dublin for a master’s in creative writing and divided his time, in his own words, between “trying to be the new Hunter S Thompson” and surfing the world-class, empty waves that surround Bundoran. He eventually settled near the coast and now teaches English. You’d imagine the highly literate, American, often mohawked, big-wave surfer has made an impact on the teenagers at the local high school.

“I didn’t know Barry that well in the early days, but I knew a guy was running around who was a South African version of me,” says Stott. “Eventually, we met through a mutual friend and we partnered up.”

Mottershead grew up where the urban sprawl of Cape Town gives way to South Africa’s craggy and sparsely populated western coast. A keen surfer, rock climber and kayaker, he dreamed of adventure and, as soon as he finished high school, he sold his car and bought a plane ticket to Europe.

He’d read about the amazing waves and landscapes of the Irish coastline, a stark contrast to the dry and dusty landscape he was used to at home. Like Stott, he fell in love with the coast, the waves, the Irish way of life and a local lass. Now married, the couple had their first baby, a boy, three months ago.

Stott and Mottershead’s arrival in Ireland came at a pivotal point in big-wave surfing. In the late 2000s, tow surfing, where surfers use jet skis to access huge waves that otherwise cannot be paddled into, evolved. One wave, located on the far western tip of Mullaghmore headland, was in that bracket.

Stott, Mottershead and a select crew of locals were the first to bring tow surfing to Ireland. The wave, located just below Mottershead’s house, has played a huge part in their staying in Ireland and their friendship.

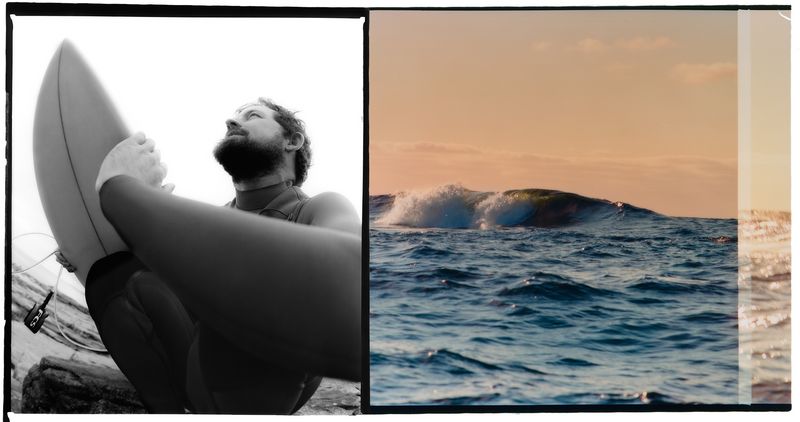

“You have to remember that tow surfing waves as high as 50ft was pretty new, even in the established surfing hotspots like Hawaii and Australia,” says Knight, who at 26, is the youngest of the trio. “Barry and Dylan were true pioneers who made the impossible possible. They weren’t doing it for the money or the exposure. It was just for the thrill.”

For Mottershead, it wasn’t just the adrenaline rush, but the novelty of big-wave surfing that got him hooked. “The thing that drew me to the big-wave aspect of surfing was that we were treading our own path and you could surf waves that no one had surfed before,” he says. “It wasn’t an ego thing. It was just that it was special because it hadn’t been done before. We felt like astronauts.”

Another by-product of tow surfing was that surfing, historically a solo pursuit, became more about teamwork. The surfer riding the waves had his life, literally, in the hands of his partners.

“With so few of us doing it, and relying on each other so much, personal differences have to be talked through, made open and solved. It makes for stronger friendships”

“With so few of us doing it, and relying on each other so much, personal differences have to be talked through, made open and solved,” says Mottershead. “There’s almost no other way if we wanted to keep doing what we loved. It makes for stronger friendships.”

“Barry is so organised and methodical, while I’m very emotional, and impulsive,” says Stott. “I need that and trust his decision-making sometimes more than my own. That extends way beyond just our big-wave surfing.”

Knight grew up on the North Devon coast in the UK. Both his parents were sailors, as he is, and as a talented competitive and big-wave surfer during his teens he had dreamed of making it as a pro. While completing a physics degree at Bristol University, he made frequent trips over to Bundoran to surf the incredible waves, as well as indulge his new passion for rock climbing.

Three years ago, he bought a derelict house 50 yards from the seafront in front of Bundoran’s well-known wave, called The Peak, and has been slowly doing it up on his own. This summer he worked as a surf instructor to help fund the restoration project.

“The first winter he had no windows, heating or toilet in the house,” says Stott. “He’d turn up to surf, covered in plaster, wearing three pairs of socks and four coats, but always with a smile. Taz is way older than his years. He has sailed some of the world’s most treacherous ocean passages and surfed some of its biggest waves. He has suffered through ocean hardships that men twice his age have, but he’s bought so much positive energy to our little community.”

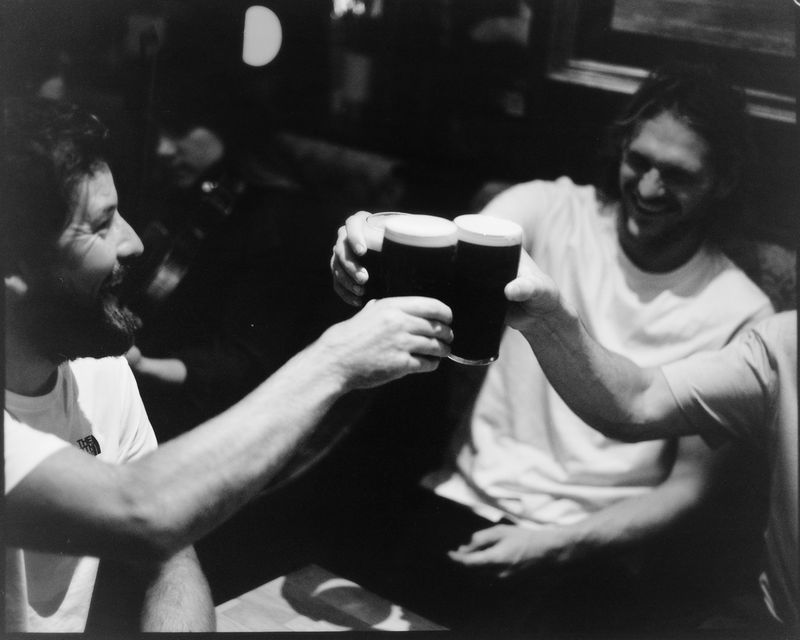

While surfing may have been their original common passion, for the three ex-pats living on the edge of the Emerald Isle, the friendship extends far beyond riding waves. Be it hiking, climbing, kayaking or the obligatory pint of Guinness in the local pub, they rely on each other in times when surfing isn’t an option, which can be weeks on end.

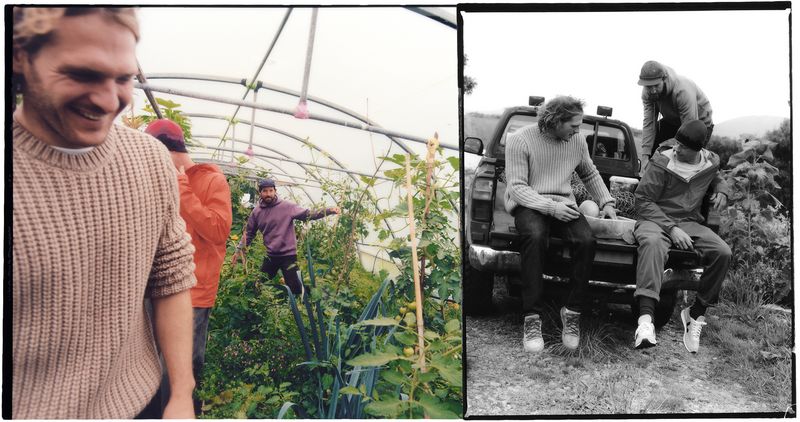

More recently, they have been congregating on Stott’s organic farm in Mullaghmore. In between trimming beans, picking corn and watering artichokes, they discuss the surf, their life plans and the things that matter.

“To stay and try and flourish in this harsh environment has been such a special experience,” says Mottershead. “I couldn’t ask for more, and to have two brothers like Dylan and Taz to share it with and watch over me through thick and thin has meant the world to me.

“It feels like all we used to live for was the big waves and the time in between was the downtime. Now that’s just life and, as the seasons roll into each other, I can look back on what has been an amazing 20-year joyful experience. And it’s nowhere near done yet.”