THE JOURNAL

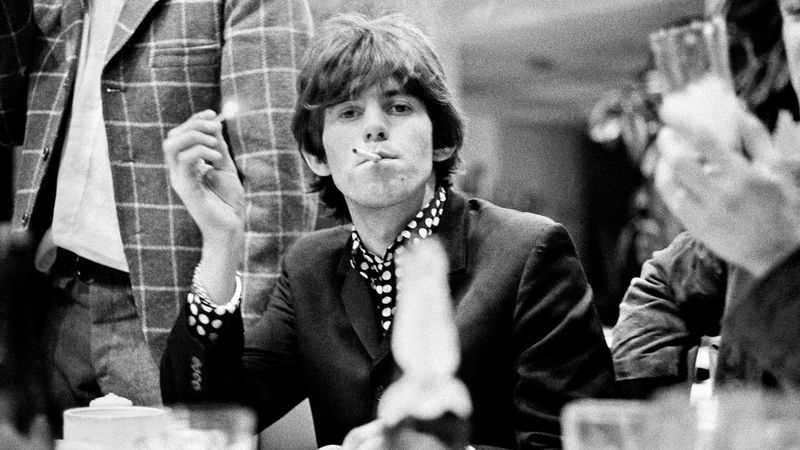

Mr Keith Richards in Paris, April 1966. Photograph by Mr Jean-Marie Périer/Photo12

Some years ago, while on a train attempting to hide from a colleague behind a copy of The Telegraph, I came across a baronet who had recently met his demise in the obituary section. He owned a shipping line, two castles and took 40 friends to St Petersburg each year for the Winter Nights. The headline announced his age and explained his life simply: he had, it said, “devoted himself to having a lovely time”. It was meant drily, The Telegraph’s obituarists being masters of the rapier cut, but it struck me then, as it strikes me now, as just about the nicest description of a life I could imagine. It’s great, I am sure, to have a castle and all that, but much the best part is the having of a “lovely time”. It is the life we should all lead. Everyone, in their way, ought to be a hedonist, someone who seeks pleasure and avoids pain.

Picking up the newspaper that day in February led to one of those rare moments of enlightenment that rise like snowdrops, unexpected but welcome. It occurred to me, while still shielded by The Telegraph’s acreage, that the greatest trick the devil ever pulled was convincing the world that hard work is somehow godly. Success, as anyone who has been near it (and is honest) will tell you, is a matter of charm, brains, piranha-like cunning, connections and copper-plated self-confidence. Oh, and lots of luck.

The people who claim that hard work will set you free, raise you up, are usually those who benefit from your hard work: cabinet ministers, senior civil servants, oligarchs and so on. We might refer to these, for the purpose of developing our philosophy, as the bores. If you ever hear any of their number exhorting the populace to enjoy themselves a little more, to drink deep of the pleasure of life, then do send MR PORTER a furious letter telling us so. I suspect, though, we will not be inundated. The bores, on the whole, want us all to become droning automatons, algorithms that draw breath. They want this so that they can become rich and hedonistic.

Which is not to say that work and hedonism are incompatible. Far from it, although they have the potential to be. The clever hedonist sets out to find a job in which his interests collide with his work. And at any rate, learning, the most profitable form of work, can be just as pleasurable as a martini in a first-class compartment.

Mr Peter O’Toole, c. 1968. Photograph by Getty Images

The world of the pleasure-seeker must, however, be split into successful hedonists and failed hedonists, the latter taking in everyone who has fallen in the line of fire from drugs, a surfeit of booze and/or syphilis. The trick is to not let any of those saboteurs get hold of you, for they are the death of the ethos, being not very pleasurable at all.

In antiquity, the Cyrenaics were perhaps the first successful ultra-hedonists. In the fourth century BC, Aristippus of Cyrene, a pupil of Socrates who rejected the old man’s prescriptions, spouted the construe this way: pleasure is the goal of life, achieved by maintaining a control of adversity and prosperity – and being altruistic as you go. Never did him any harm. Epicurus in the next century said pleasure was the goal, but it ought to be modest, the greatest pleasures being friendship and knowledge.

“Pleasure is the goal of life, achieved by maintaining a control of adversity and prosperity – and being altruistic as you go”

Much later, Lord Byron came to embody hedonism, or at least the sort of excess with which we now associate the word. That his poetry survives as much as his legend surely counts for the good. Mr John Wilmot, Earl of Rochester and Restoration wit and writer, was most definitely a hedonist, but, as the essayist Mr William Hazlitt wrote, he had “extravagant heedless levity” and that lead to the rocks – drink, dissolution and syphilitic madness. Mr Oscar Wilde was something of a hedonist, too, and was also a little heedless. Good work, but all the fol-de-rol didn’t end well.

Much happier, perhaps, are the examples of Mr Peter O’Toole, the actor, and Rolling Stones guitarist Mr Keith Richards, who managed to go out for milk and find themselves on a bender in Istanbul and yet still managed to produce fine art and be internationally rich and famous. It is a thin line, but you can dance to it. I suppose the guiding principle is, if it kills you, you are doing it wrong.

Naysayers argue that hedonism is a philosophy of despair, that the reason to seek pleasure is because life unfurls in unending unpleasantness. The pleasure is a momentary release from bondage. Not so. Pleasure is as much a part of life as pain and horror. They are the material of the day-to-day. Hedonism is actually about optimism. It is to say, and indeed to experience, the kindness of life, to say and believe that life is worth the salt, to see a glimmer of hope.

From that recognition comes a desire to give joy to others. Hedonism is a friendly condition. I find that if I have a belly laugh before lunch, the day goes much more smoothly. And if you enjoy life and enjoy its ridiculousness, then laughter is a constant companion. And when you laugh, are high-spirited, buy just one more round, give that bit more of your time for conversation, give someone the full focus of your attention, you are enhancing your own life as well as the lives of those around you. Hedonism encourages the tolerant virtues of kindliness, constancy, bravery (for it cuts against the grain) and a commitment to others. Hedonism looks out on the world and smiles.

Being a hedonist might expose you to ridicule. It might mean you earn less, that you enflame the bossy booted and the bores. But if, when all is said and done, and St Peter calls your first character witness, if all they can say of you is that you added 0.1 per cent to the GDP, then you probably ought to be buying up absolutions now – and don’t trip over the line of hedonists on your way out.

Oh, and the person I was hiding from was such a bore they might have used him to dig the Channel Tunnel.

The men featured in this story are not associated with and do not endorse MR PORTER or the products shown