THE JOURNAL

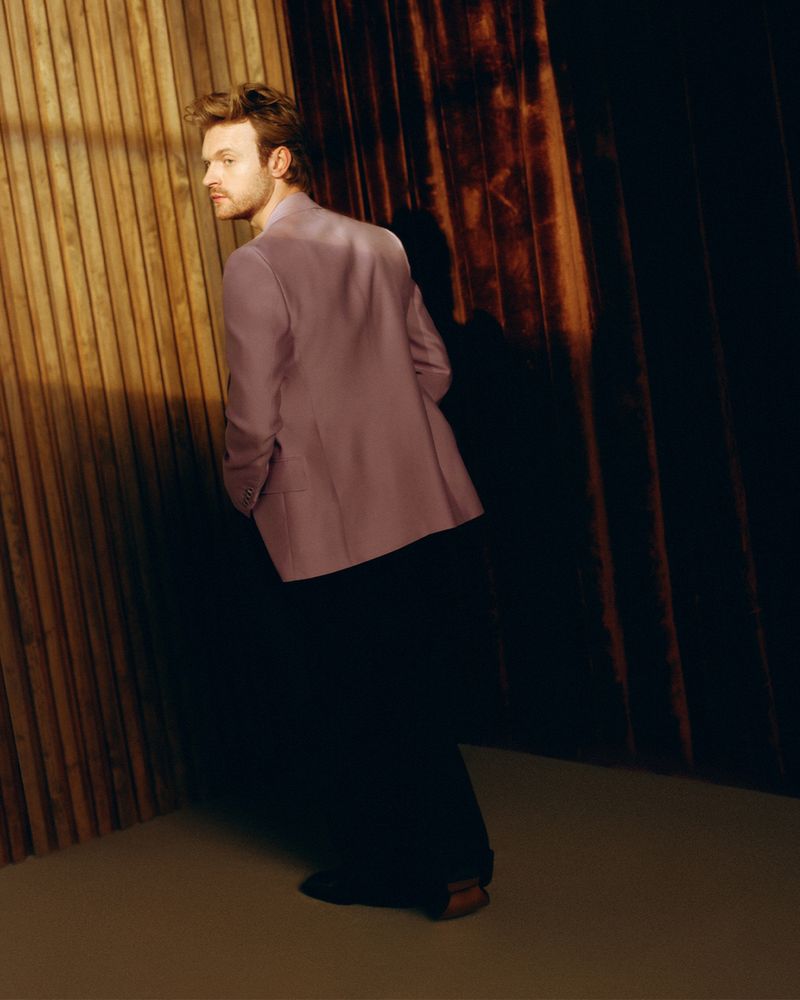

Ping! Half an hour before Finneas is due to arrive, an email appears. He has received three nominations for the 2024 Grammys, among them are nods for both Record and Song of the Year.

Ping! Fifteen minutes before Finneas is due to arrive, an email appears. It has been confirmed (though not yet made public) that he will be creating the score for the Oscar-winning director Mr Alfonso Cuarón’s next project. Disclaimer, a multi-part thriller for Apple TV+ starring and executive produced by Ms Cate Blanchett, will premier in 2024.

At 26, Finneas has emerged as one of the most prolific men in the music industry today. You have, without question, heard something he has made – that is, unless you don’t own a radio, or use Spotify or watch movies. Or if you lived in space this summer. There’s no other way you could have avoided “What Was I Made For?”, the plaintively compelling contribution that he produced for the record-shattering Barbie movie, and the reason for his nominations.

Oh, and there’s his sister, the musical supernova Ms Billie Eilish, his creative partner and one of the most visually iconographic pop stars of the new millennium.

And yet, despite having spent the morning receiving the kind of career validation that most could only dream of, he’s almost preternaturally unfazed. “I’m not a super present person,” he concedes. “It’s not a good quality. I’m always thinking about the next thing.”

Still, he’s looking forward to the Grammys, now that the pressure of being a newcomer has long passed – he and Eilish have already won what he demurely refers to as “a few”. Eight in the past three years, to be exact, with 17 nominations to date. And an Academy Award. And a Golden Globe. And so on.

“It alleviates some desire,” he says. “I don’t feel desperate to win again. I’ll be happy just to sit there and clap for everybody.” If his good sportsmanship is an act, it’s a convincing one. At the 2022 ceremony, when Mr Jon Batiste beat Finneas and Eilish to win Album of the Year, the duo were among the first on their feet, whooping for Batiste as he ascended the stage.

The titanic success of Barbie (and that’s the right word: at the time of writing, it’s only 10 places behind Titanic on the list of the highest-grossing movies ever made) was this year’s defining pop-cultural moment, heralded as a life-raft for a beleaguered industry in a year dominated by box-office flops and strikes. “We knew it was going to be the biggest movie of the year,” Finneas says. “Even before we saw the movie, we knew. I would have bet big, big money on that.”

The song itself was conceived in a single day, taking its cues from the film’s opening sequence, and achieves something remarkable – it takes the frothily comic premise of the movie and transforms it into something with real emotional punch. It was eventually used to score the film’s dramatic climax.

“We were floored the first time we heard it,” recalls Mr Mark Ronson, who produced the soundtrack and enlisted a roster of musicians to contribute songs for it. “The demo was so wonderful that we couldn’t imagine what they could add to it, or what was even needed.”

Though the shortlist for the Academy Awards hasn’t yet been announced, it’s widely tipped to receive a nomination there, too. It’s a satisfying end to a project that many on Finneas’ own team were initially hesitant about.

“We just knew it was gonna become this huge, zeitgeisty thing,” he says. “We work with a bunch of really smart people, but not all of them are 21, or 26, which Billie and I are. So, we had a different perspective on it.”

The backstory of Finneas and Billie O’Connell (their real surname; Eilish is one of Billie’s middle names) is the stuff of modern pop legend. Raised and homeschooled in Los Angeles, the pair spent much of their adolescence creating music together in their childhood bedrooms, writing songs as a means of expressing Eilish’s teenage angst. Those would go on to form her 2017 EP, dont smile at me, and its follow-ups, 2019’s When We All Fall Asleep, Where Do We Go? and 2021’s Happier Than Ever. The albums, combined with Eilish’s pop-punky, anime-meets-hip-hop visual style and unguardedly confessional relationship with her fans, utterly reshaped contemporary music and spawned countless imitators.

Her level of reach, especially among Gen-Z audiences, is almost unfathomably huge. According to Spotify, on average, her songs have been streamed some 130 times per second since her 2016 debut.

Fans have flocked to the heartbreaking sincerity of Eilish’s lyrics (“I’ll try not to starve myself / Just because you're mad at me”) as well as the impishly playful nature of Finneas’ compositions. The production on their tracks is singularly and intentionally erratic, incorporating snatches of windows being smashed, matches being struck, and aural distortions of Eilish’s own laughter. The duo switch willfully and gleefully between genres, often within a single song – within the space of five minutes, the title track from Happier Than Ever lurches from lilting jazzy ballad to bedroom-trashing primal scream.

In a music industry increasingly dominated by algorithmically built tracks that are designed to appeal to the lowest common denominator, Finneas’ work has demonstrated the value of the curveball. In doing so, he has carved out a territory in the landscape of music today that is his, and his alone: a corner that Ronson describes as “insanely hooky, but weird”.

To keep him occupied as a teenager, Finneas’ mother would set him and Eilish a game: to create pieces of music inspired by the characters they watched on TV, on shows such as The Walking Dead. “It was a really good exercise”, he says now. Certainly, it helped to shape his ability to hop, Frogger-like, across musical boundaries. But it laid the foundation, too, for his movement into TV and film.

“He has a wonderful sense of aesthetics about him,” says the composer Mr Hans Zimmer, who worked alongside Finneas on the soundtrack for the 2021 James Bond movie No Time To Die. “Not all brilliant musicians are capable of scoring,” Zimmer says. “They don’t always know how to respond to the images. But Finneas does. He’s very, very smart.”

If Barbie and Bond were Finneas’ training montage, Disclaimer might be his biggest showdown yet. He estimates that he has, to date, produced more than a hundred pieces of music for Cuarón. “It’s incredibly all-consuming,” Finneas says. “It’s creating a world. And that was the challenge, and the fun part – taking this seven-part series and making it this one cohesive thing.”

Cuarón and Finneas first met some years before, when the director took his then-teenage daughter to one of Eilish’s concerts in Milan. “I figured that he loves his daughter, and he’s bringing her to whatever she loves,” Finneas says. “And that would be how much he knows, or cares, about what I’m making. I couldn’t even look him in the eye.”

“It’s creating a world. And that was the challenge, and the fun part”

Instead, Cuarón struck up a conversation about the sonic effects on one of Eilish’s early EP tracks. The two swapped numbers, and soon began sending each other playlists. “I remember sending him “Ponyboy” by SOPHIE, and him being into it. That was pretty awesome,” Finneas recalls. Their friendship led to Finneas and Eilish contributing a song to a special-edition album inspired by Roma, the film for which Cuarón won his second Oscar in 2019. But it wasn’t until early 2022 that the possibility of working on Disclaimer first came up.

Though Finneas had, at this point, worked on No Time To Die, the scale of what he was being invited to contribute was overawing, to say the least. “If this was my first film project, I think I would have fallen apart,” he says.

Instead, he quickly signed on to a couple of other film projects as a means of teaching himself the ropes. “You push yourself hard, and you get better,” he says. “But still, I love that feeling of impostor syndrome. That feeling of being in way over my head. It’s how I felt when I made Billie’s first album. I love it. Though it doesn’t help me sleep at night.”

As the project slowly begins to come together, Finneas has relished the nature of the collaboration. “It’s like being a handyman,” he says. “You’re there in service of the director. It’s total ego-death. And you have this canvas in front of you with all this inspiration. So, I love it. I love writing from a non-autobiographical place.”

Wait. What? This, from the man who helped to create some of the most emotive, anthemically confessional music of the last decade?

“It’s like this,” he says. “If I say to you, you have to write the most honest, vulnerable song… first of all, you have to know exactly how you’re feeling. And then you have to say it out loud and put it down. And that’s a big, tall order.”

He pauses to think. “You know, maybe you feel embarrassed to do it, or like your emotional response to something is foolish. But more than that, most of the time, most of us aren’t sure which emotion we’re processing. It’s only in retrospect that we understand ourselves. You know?” he laughs. “Like, maybe you were just hungry that day.”

That’s the thing about Finneas. Despite the ease with which he and Eilish seem to be able to access the most personal yet universal of fears, emotions and anxieties, he’s remarkably clear-eyed about what it is that he’s creating.

“He’s good at knowing what he doesn’t want,” Zimmer says. “As soon as you get sentimental, he bristles, and turns away.”

In that sense, he’s the yin to Eilish’s yang, his pragmatism offsetting her deep sensitivity. There’s a moment in The World’s A Little Blurry, the 2021 documentary about the duo, when Finneas and Eilish are caught discussing the potential commercial appeal of the music they’re recording. “I’m never gonna do anything, ever, if I think that way,” Eilish says.

“You don’t have to think that way,” Finneas says. “But I can.”

“We probably need each other so much in that way,” he says today. “I was a very emotional little kid. Very high highs and really low lows. And, at some point, I traded that in for regulation. Like, the meanest comment on the internet doesn’t make me hate myself, and the nicest thing a person could say doesn’t make me love myself. I’ve watched people suffer at the hands of both of those.”

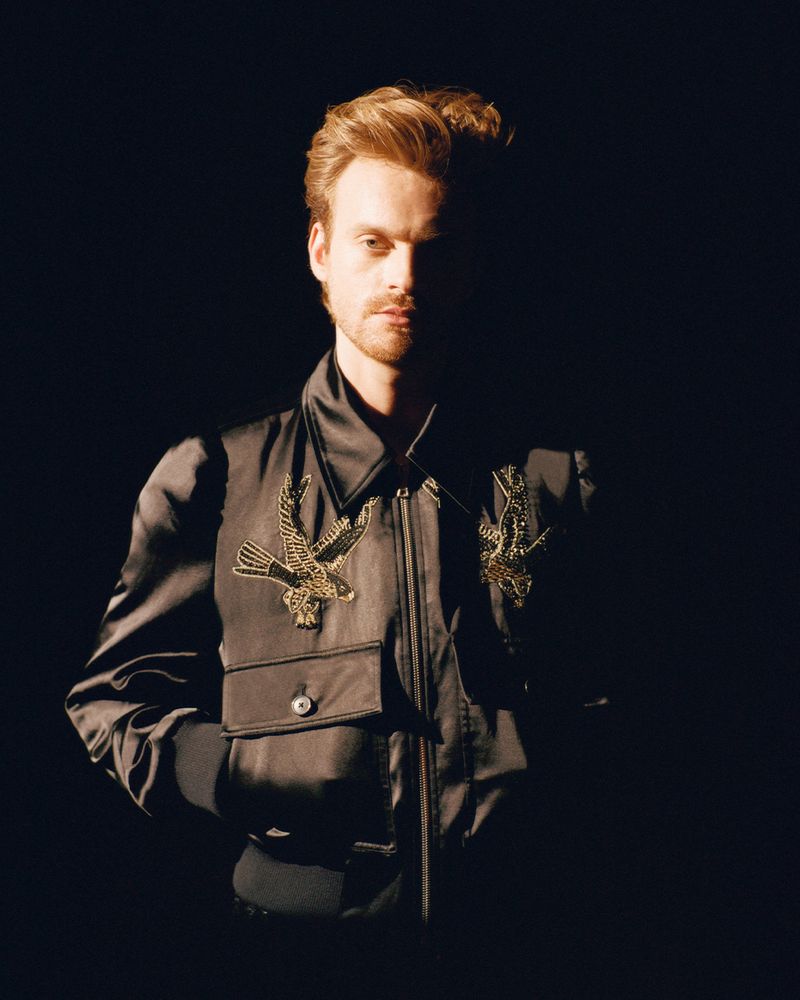

Living and working in the orbit of his sister’s mega-stardom has shaped Finneas’ own perspective on fame, and what he wants from his own career. “I have no idea what I’d think about it if I weren’t exposed to the limitations of her life,” he says. Recently, he was stopped by a fan, who asked for his advice on how to become famous. The experience threw him. “She was like, ‘I just want to be in the spotlight,’” he says. “And I was like, no, you don’t. You really, really don’t.”

In that sense, the level of fame he has achieved now is where he’d like to remain. He’s highly regarded in his field, and respected for his work. But there’s no Twitter accounts dedicated to the current colour of his hair, or tracking where he is in the world right now. “You know, maybe one person a day comes up to me and says hey, you’re Billie’s brother, right? And it’s always nice. But there’s no mob.”

By way of contrast, he describes a recent episode, when Eilish paid a visit to a friend’s concert. The moment that word spread she was in the building, half of the audience turned away from the stage, phones aloft towards the balcony where she stood, ignoring the artist she had shown up to support. “It’s been eye-opening,” he says. “Everything that is normal for me is an undertaking for her.”

Finneas describes their next album as “85 per cent done”. He recalls a quote from Mr Ken Caillat, who produced Rumours with Fleetwood Mac: you don’t finish albums, you just give up on them. And this one, in particular, has been challenging. Over the summer, Eilish spoke at length in interviews about the writer’s block she and Finneas felt while trying to develop a follow-up to their two globally adulated records. Now that this album is at last coming together, Finneas has gained some perspective on that period.

“The meanest comment on the internet doesn’t make me hate myself, and the nicest thing a person could say doesn’t make me love myself”

“I don’t think Billie was particularly sure about how she actually felt about the things we were trying to write about,” he says. “Making a thing that you feel really connected to – it can really evade you.”

And besides, he says, he’d spent very little of the past year writing, with such an intense touring schedule (88 shows, in a little over a year). “I think I got a little rusty. And that was scary. It was discouraging to realise that if I take time off, my songwriting muscle atrophies. I had to get back in shape.”

Going into 2024, though, he’s trying to bring a little more balance to his work. “I love to create,” he says. “But I don’t love drowning in it. So, I’m trying to have a more regulated relationship with it. I’m producing responsibly,” he laughs.

Over the holidays, he’ll take a short reprieve, which he hopes to spend cooking with his girlfriend. (“I like to make the elaborate stuff,” he says. “You know? The stuff you have to bake.”) Most of next year is already plotted out, between Disclaimer and “Billie 3”, plus, the work he’ll do for other artists, which he can’t speak about yet. So, the week after New Year, the wheels will start turning again and Finneas will go back to the business of making extraordinary things for other people.

“I’m a vehicle,” he says. “And I wouldn’t have it any other way. I don’t need people to look at me.”