THE JOURNAL

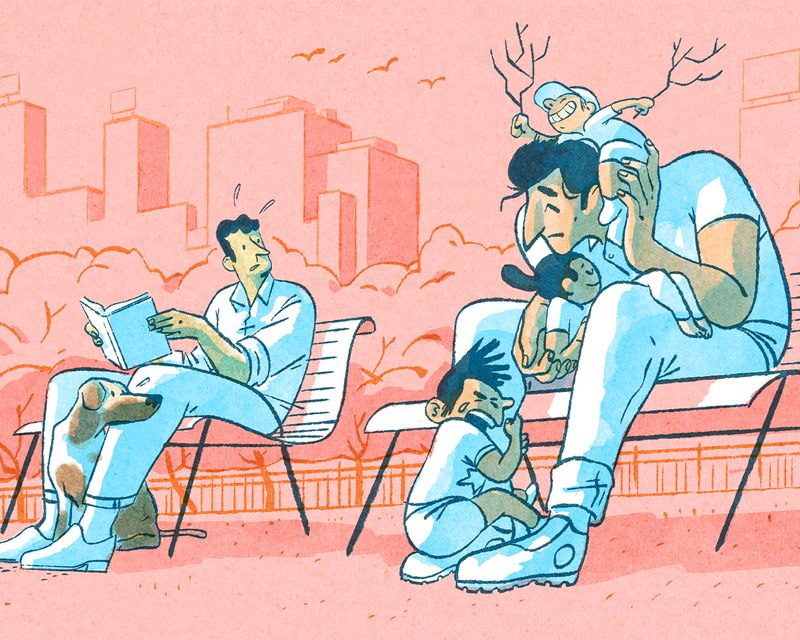

Illustration by Mr Luis Mendo

Last November, two months shy of my 32nd birthday, I had a sudden realisation. I was exactly the age my father was when I, his first child, was born. For my parents, part of the boomer generation, married in their early twenties and settled in their first and only home together not long after that, having children was inevitable. But for modern men, not so much.

According to the latest figures from the Office Of National Statistics, the birthrate in England and Wales fell by a massive 4.1 per cent between 2019 and 2020. This isn’t entirely pandemic-related, either. A 2018 study by the Pew Research Centre found that in the US, 27 per cent of child-free adults under the age of 50 never saw themselves becoming parents.

When it comes to men in particular, a 2020 Reddit poll revealed economic insecurity and the state of the world as the main reasons they did not want to become parents. From economic downswings, Covid-19, to a shift to the political right, and an increasing distrust of those in power, we’re certainly living in tumultuous times.

Mr Lee Chambers, a psychologist and wellbeing consultant, adds that fewer men are becoming fathers because many now feel that they haven’t reached adulthood until later in life. “This ties in to taking longer to hit the traditional milestones of home ownership, career advancement and marriage that sometimes precede becoming a father,” he says. In other words, it’s taking longer to build that stable base from which to build a family.

Growing up, I’d always enjoyed spending time with younger cousins or other people’s children because it was easier than making conversations with the adults. And, because, after a period of messing about with the kids, we’d go our separate ways, to separate homes. Now, in my early thirties, I (perhaps selfishly) value my own time and my peace and quiet too much to contemplate bringing something into the world so precious and helpless.

And what about plans and ambitions? A few days ago, I text one friend, who is a father, to tell him that another friend had just had his first child. He replied, “Ha, his life is over.” Personally, there are still things I want to achieve, like owning my own home, writing a novel more than a handful of people might read and travelling to remote and wonderful places.

Plus, having recently achieved a moderately comfortable existence, I’m reluctant to divert my earnings into baby shoes and nappies. In the words of the inimitable Ms Kathy Burke “If I have a kid, then all of my money has got to go on this kid… If I have money, I want to spend money on myself…I had a dog for a while and that’s fucking hard enough.”

I, too, have a dog and can confirm that it is fucking hard enough. I love my dog like a son, but I sometimes question that when he wakes up at 5.00am and starts loudly stretching and scratching. I’m uncertain about giving up my time or dreams to dedicate my life to a child who, in 25 years, will then give up their dreams to raise another child, and so on. Thankfully, my partner feels the same.

The vast majority of my male friends and their partners share similar sentiments. Mr Jake Tyler, 37, an author and mental health advocate originally from Essex, touts climate-change fears as one reason he doesn’t want to bring offspring into the world. Tyler is not alone in worrying about bringing children into the world in a time of crisis. According to a report published in the journal Demographic Research, fertility levels across Europe fell following the 2008 recession, and have done so at other times of instability. Conversely, it’s the reason my parents’ parents’ generation got so busy in the stable decades following WWII.

“You never feel ready to have children. The act of having children makes you ready. Children form you as much as you form them”

Which isn’t to say I don’t understand why people do have children, or still enjoy spending time with them. A close friend, Dr Joel Edwards, also 32, is a doctor based in Leicester and has three children under the age of five. He says that he and his wife always planned on children. “We had a debate about whether to wait and get other things done, or just get on with it. I think we thought it was best to have them younger, put our own ambitions off instead of having children a bit older and maybe not being able to do as much with them or enjoy it as much.”

I asked Dr Edwards about the common worry that fatherhood means giving up your own time. “Sometimes you see other people going on holiday last minute or socialising and you miss out on that,” he says. “But I’ve got something different to enjoy. My favourite days are when I get to act like a kid. If we go for a walk, we’re fully engrossed in that four-year-old mindset, just being on their level and enjoying the moment. I go to the zoo and the local farm once or twice a month. Fun stuff you wouldn’t do as an adult.”

Another friend, Mr Daniel Garnham, 37, is a former reception schoolteacher and now co-runs his own nursery in Hove, East Sussex. His first child, a daughter, was born just under two years ago. “I’ve always wanted to be a dad,” he enthuses, his reasons similar to my own: “As a kid, if we went to someone’s house I always wanted to play with the kids, not talk to the adults. It was more magic. Children are looking for magic and they find it. Adults don’t – that’s the beauty of it.”

As a schoolteacher, Garnham says he “always felt like a dad without children” and that “If my partner had let me have children earlier, I would have done.” Crucially, though, he says his mid-thirties was the right time for him to become a father in terms of his own maturity and being ready to not put himself first anymore.

As for the negatives, Garnham does admit it can be hard. “People think about screaming children, tantrums… and the lack of sleep is terrible. But all of those things pale into insignificance compared to the love you feel for your children, so it really doesn’t matter.”

“You can become a father and still make an impact on sustainability and regeneration, or you can be childless and make an impact on the future of the next generation”

Maybe, for many men, it’s not so much a question of never having children, but timing. I find myself becoming more and more sentimental around children. Recently, on a plane I caught myself tearing up at the sight of a father buckling his young son into his seat. At the same time, I was happy I was in my own company.

“You never feel ready to have children,” Davies explains. “The act of having children makes you ready. Men expect that they should wait until they feel ready but children themselves create a father. Children grow up slowly. Make the most of the opportunity. If you’re waiting to be a good role model for your child, then don’t, because children last a lifetime and they will form you as much as you form them.”

Ultimately, I recognise that it is a tremendous privilege to bring children into the world and that many men, women and non-gendered people struggle or find it impossible to do so. Speaking with fathers has helped me understand the nuances of fatherhood a bit more. Assuming I will be able to have children when I’m older, and my partner also wants to, perhaps it’s wiser to leave that option on the table.

“Fatherhood isn’t an all-or-nothing decision,” Chambers says. “You can become a father and still make an impact on sustainability and regeneration, or you can be childless and make an impact on the future of the next generation. What is important is that we find peace in our decision, know that this may change, and do what we can to make a positive difference that makes us feel fulfilled and purposeful.”

I like to hope that I can be a positive influence in my friends’ children’s lives and, if I ever have my own children, their lives, too. Until then, the next time my dog wakes me up at 5.00am, I will try to remind myself that I love him and am lucky to have him.