THE JOURNAL

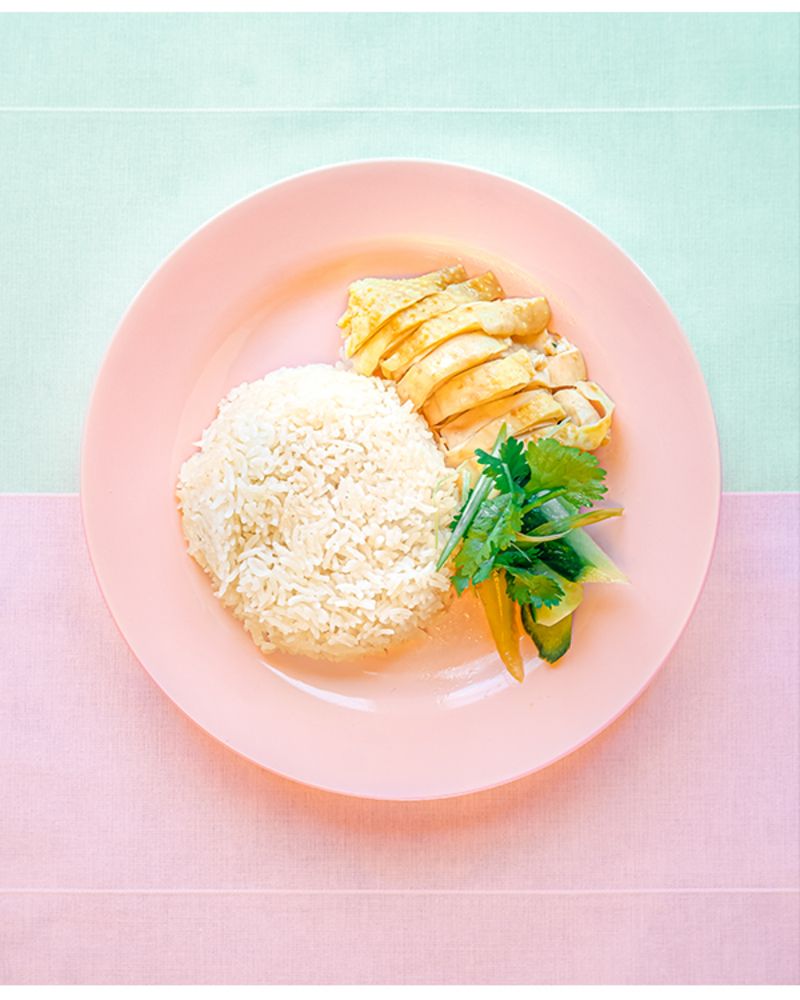

From left: Plantain waffles at Chuku’s, Tottenham. Photograph courtesy of Chuku’s. Hainanese chicken and rice at Mei Mei, Borough Market. Photograph courtesy of Mei Mei. Pork lechon at Sarap, Brixton Village. Photograph by Mr Lateef Okunnu

As London’s second-generation immigrant chefs start to come into their own, it’s only natural that they want to create food that is much a personal expression as it is the continuation of the story of a national cuisine. But how to satisfy the demands and expectations of an audience unfamiliar with the cuisine and the expectations of another whose perception of the “authentic” is frozen in time? Food writer Mr Jonathan Nunn sits down with the chefs behind three of London’s most exciting new restaurants to find out how they’re doing just that.

01. Chuku’s

Mr Emeka Frederick and Ms Ifeyinwa Frederick

Plantain waffles at Chuku’s, Tottenham. Photographs courtesy of Chuku’s

Despite an exhausting first week of opening a restaurant, siblings Mr Emeka Frederick and Ms Ifeyinwa Frederick are in a buoyant mood. It’s been a slow journey: years of street food and pop-ups, followed by a crowdfunding which quickly secured them the money for their first restaurant, with some left over. Now, that restaurant, Chuku’s, is finally open, close to Seven Sisters station in Tottenham. The Fredericks’ aim is to move Nigerian food out of the shadows and into the mainstream, using a communal, participatory atmosphere and a sharing plate structure familiar to most Londoners in a way that doesn’t water down the food’s Nigerian-ness. They want Chuku’s to be more than a restaurant; they want it to be a space where any open-minded Londoner, Nigerian or otherwise, can take home something more than a full stomach.

You’re going to have a lot of people walking through your door who have never tried Nigerian food before. You’re going to be their introduction.

Ms Ifeyinwa Frederick: I guess it’s about honesty, or rather transparency. In the sense that we don’t pretend to represent the entirety of Nigerian cuisine, because the country is far too vast, and I think you use the right word when you say “introduction”. We will give you a taste, we can’t give you the cuisine in its totality. When we’re training the team we have to be clear that not everyone in Nigeria eats plantain waffles. I feel it’s a real privilege to be someone’s first introduction – we get a lot of people coming in where one person is Nigerian and one person isn’t and it’s a privilege to be that person’s point of education.

You told me your biggest concern when you opened Chuku’s was the perception that you are not being authentic. Did that criticism manifest, or has the response been positive?

**Ms Frederick: **No, it’s there, it’s on social media. But that’s people. Definitely the balance is good. When I see [criticism], I think, “That’s just you and that’s OK”. Some say, “What even is Nigerian tapas?” Or, “Why would you do that?” But that’s fine.

**Mr Emeka Frederick: **We may present Nigerian food differently, but in terms of the flavours, it is there. The key components of those dishes are there and we can provide authentically where the direction has come from. When you have people who eat that dish in a traditional way and then they see it presented in an innovative way but can taste the tradition in the dish, that’s amazing.

Are there Nigerian dishes you love that you could never put on the menu, or is nothing off limits? Could you do a small plate isi ewu (goat’s head), for instance?

Mr Frederick: I think for many Nigerians, especially for Nigerians living in London, a dish like isi ewu would be difficult! Ifey and I had this dish nkwobi – another Igbo dish – and there’s a number of people who love it. I thought it was the most disgusting thing I’d ever had to be honest. But that’s food! One of the things people always ask about is spice levels: “Have you dialled it down?” No, actually. For us, eating Nigerian food at home, my mum didn’t use much spice in her jollof rice. But my aunty makes it hot. Spice is just a seasoning. There are some dishes that are hot, quintessentially hot and that means when we do that dish, we do it hot.

274 High Road, Tottenham chukuslondon.co.uk

02. Mei Mei

Ms Elizabeth Haigh. Photograph by Mr Daniel Harris, courtesy of Mei Mei

Hainanese chicken and rice at Mei Mei, Borough Market. Photograph courtesy of Mei Mei

Ms Elizabeth Haigh is the owner of Mei Mei, a Singaporean kopitiam, or traditional Asian coffee shop, in Borough Market. Ms Haigh’s career has almost happened in reverse. Born in Singapore and raised in the UK, Ms Haigh hit our TV screens in 2011 on MasterChef, before taking on the head chef role at Pidgin, the Hackney restaurant where the constraint was simply that no dish could ever be repeated. A Michelin star followed, but Ms Haigh left Pidgin soon after to open her first restaurant Shibui, which has been in limbo ever since. Seemingly out of nowhere, Ms Haigh then announced she would be opening Mei Mei in Borough Market, a barely covered stall, selling the food of Singapore’s kopitiams, specialising in a dish a world away from fine dining – Hainanese chicken rice. Go today and you can spot Ms Haigh straightaway, carving up chickens for the London Bridge lunchtime crowd, which has swelled off the back of rave reviews.

You’ve gone from having free rein to cook what you like to being constrained by the boundaries of Singaporean cuisine. Why did you decide to do this?

After doing Pidgin, where we were changing the menu every week, it felt like it was too much change. I wanted to do something that I knew inside out, and I had so much respect for the cuisine back home. I don’t feel like there’s any constraint with Singaporean cuisine because it covers nearly every cuisine there is. It’s like London. It’s an island cuisine, so you’ve got influences from everywhere, so I never went into Mei Mei thinking I was constrained because it leads into so many other areas.

The problem with leading with chicken rice is that you have to teach the British to love cold poached chicken. How is this going so far?

I had so many reservations about doing it, so maybe that’s why we made a point of making it our signature dish. People need to be pushed into the deep end. But that’s also why we put the deep-fried chicken version on there. I saw it on a menu in Singapore and I thought, “That’s brilliant. Why has no one done that before?” Once people get past that poached aspect, it’s fine, although I did overhear some customers today saying, “Is it just boiled chicken?” And I wanted to say, “There is a big difference between boiled and poached.” Maybe it is just this British obsession with boiled things.

**Another thing is the reaction of Singaporeans, who have a lot of opinions on good food. How do you deal with these strong opinions? **

These are home comfort foods. Their mothers and their grandmothers had their own particular way of doing them and that’s just ingrained in how they like it. Literally every other Singapore customer says, “It has to have a bit more of this, or less of that,” but I’m the one cooking it. I can’t do every version of chicken rice. We do try to improve the sauces a lot. With the nasi lemak, we changed the sambal. It was too shrimpy for everyone. I remember I tweaked the ginger paste. I had to cook out the garlic for a bit longer because it was too strong for the Western palate. And then immediately a Singaporean asked, “What have you done to the ginger paste? I liked it, it had so much heat!” I can’t win. The way we serve the Hainanese chicken rice is exactly the way my mother and my grandmother served it. For me, it’s the right way and I don’t know any other way of doing it.

Borough Market meimei.uk

03. Sarap

Mr Budgie Montoya

Lechon Liempo at Sarap, Brixton Village. Photographs by Mr Lateef Okunnu

Mr Budgie Montoya is a man on a mission. Born in the Philippines and raised in Australia, he is at the forefront of a loose movement of chefs promoting Filipino cuisine in London, and has just opened a new restaurant, Sarap, in Brixton. We spoke to Mr Montoya on his day off after two solid weeks of opening, to talk about the difficulties of putting his own spin on Filipino food – not that this translates into a lack of customers. Sarap has been perpetually rammed since it opened, sometimes even running out of food before closing. Its tagline is “authentic flavours delivered inauthentically”.

Your tagline almost seems like a warning to Filipino diners about what to expect.

Definitely guilty as charged in that sense! Setting the expectation first and foremost is important to me because we definitely do not do things traditionally. We deliver an authentic experience – as in, all the flavours are there and when I create a dish it’s always based on an authentic flavour profile or a memory – but in terms of delivery, it’s not authentic. Filipinos are used to getting everything at once and eating it with copious amounts of rice. I’ve seen people waiting for their food and letting it go cold just so they can have everything in one go.

**Given its fragmented nature, can there even be such a thing as authentic Filipino cuisine? **

I think authenticity should be based on the moment. I often look at Filipino cuisine as one of the original fusion cuisines. I hate that word, but we’ve had so many influences from the Chinese, from the Spanish. I care more about making sure the food is delicious. Do people want to come back and eat it? That’s my goal, not “is this how my mum made it?” There’s no getting away from it, though. Filipino customers are the most difficult to please. It’s a great challenge for me to balance the customers who have an expectation because they know and understand the cuisine and to please the customers who have never eaten it before.

You’ve said that you want Filipino food to be viewed in the same way as Chinese and Thai food in the UK. What are the barriers to this right now, and what do you see changing?

People have no reference points for Filipino cuisine. You talk to someone about Japanese cuisine and you say “miso”, not “fermented soybean paste”. If I say to someone “bagoóng”, no one has a clue what that is. The challenge is to try and create those reference points and use our language. When I do a dish, I research it extensively and I call it what it is because language is such an important part of what cuisine is. Ramen is ramen, you don’t see it called something else. I dream of a time where I call a dish ”kinilaw“ and don’t have to say underneath “Filipino version of ceviche”. Kinilaw is kinilaw.

14D Market Row, Brixton saraplondon.com