THE JOURNAL

When the world outside seems troubling, there’s little more comforting than retreating into a good book. The transportive power of literature provides much-needed respite from times of uncertainty and stress (stress? Who’s stressed?), whether that be in the form of fantasy and adventure, modern-day classics or childhood favourites – the important thing is that they have a reliable beginning, middle and end when little else does.

With this in mind, we thought that now would be the perfect time for the MR PORTER team to band together and compile a list of our favourite and most trustworthy sources of reassurance and escape.

Ms Molly Isabella Smith, Copywriter

The Secret Garden by Ms Frances Hodgson Burnett (1911)

Image courtesy of Penguin

Yes, revisiting my childhood bookshelf to cope with the scores of scary things happening in the world is almost certainly my psyche’s desperate attempt to shield itself. I can already hear Dr Sigmund Freud scoffing and muttering something about regression from the grave, but delving deep into the literary loves of our juvenescence is also a bit like getting a hug from your mum when you’ve taken a tumble and scraped your knee: exactly what we need right now. Given that I’ll be spending the totality of spring languishing indoors in a metropolitan houseshare like a modern-day Master Colin Craven, a jaunt to the wild Yorkshire moors and a visit to a quasi-magical oasis via Ms Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Secret Garden is just the tonic to see me through to the summer.

Ms Lili Göksenin, Senior Editor

Valley Of The Dolls by Ms Jacqueline Susann (1966)

Image courtesy of Little, Brown

I read Valley Of The Dolls a few years ago and was utterly blown away by it. It has one of those titles that everyone has heard of, not least because the book was turned into a movie co-starring the ill-fated Ms Sharon Tate, but few people really know what it’s about – assuming, I imagine, that “dolls” refers to the Barbie-ish girls on the movie poster. To say that this book (unfairly categorised as chick-lit) has been foundational for current cultural flashpoints is an understatement. It features three women trying to make it in New York City (sound familiar?) in the 1960s and follows them as they become famous, make ill-fated marriages, take trips to Europe for a weight loss regimen called “the sleep cure”, have affair after affair and – as the title actually alludes to – become addicted to pills (“dolls” are their nickname for pills).

If any movie deserves a gritty remake by a serious female director, this is it. But before that happens, and before you watch the original film, you should definitely read this book. It’s essentially Mad Men from the perspective of single women and similarly features some real New York cultural icons. Even if it is a bit dark (addiction is real and sad), it’s also funny and strange and pure entertainment. And it has nothing to do with viruses.

Ms Danai Dana, Sub-Editor

The Bluest Eye by Ms Toni Morrison (1970)

Image courtesy of Penguin

In times like these, when the world pauses, it’s a great time to pick up a book to escape reality, stop and reflect. And cultivate yourself with good literature, of course. Nobel Prize Winner and literary legend Ms Toni Morrison’s first novel, The Bluest Eye, follows a group of young girls in 1940s Ohio as they enter womanhood. This 20th-century feminist classic by the Ms Beyoncé Knowles, the Ms Oprah Winfrey of literature, explores the effect of society’s standards on women and how life would be easier with beautiful, blue eyes. Ms Morrison’s ravishingly raw writing depicts the racist and colourist beauty ideals of the mid-20th century US – which haunt us in this century, too – where being white and having “blue eyes” were the societal standards of beauty. Not uplifting, but never overwhelmingly dark either, The Bluest Eye urges you to let go of any expectations (of yourself and others).

Mr Chris Wallace, US Editor

Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy by Mr John le Carré (1974)

Image courtesy of Penguin Classics

It is the mid-1970s, the height of the Cold War, so nothing too terribly overt is happening – the action is all interior, all gestural, wicked, wicked antagonism covered with a smile, buried in layers of irony (there is absolutely nothing to trigger you, nothing to bring you back into our wretched present; this is costume drama from a near past or a different timeline all together). For all its allusions to grand, global intrigue, Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy is almost entirely domestic drama. It is, bar none, the most exquisitely designed plot I can think of – and it is almost entirely a book about office politics. About how poisonous the ambitious suck up can be, how vile (and even treasonous) can be the star of the firm, about the outrageous tedium and ridiculousness of bureaucracy. And I love it to pieces. For the language, for the intrigue, for the greatest human hero ever invented: the squat, plump old owl George Smiley, whose clothes don’t quite fit him, who doesn’t quite fit into the boys’ club of his job, whose wife is always running off with someone or another and whose research and reasoning saves the world.

Ms Roni Omikorede, Deputy Chief Sub-Editor

Captain Corelli’s Mandolin by Mr Louis de Bernières (1994)

Image courtesy of Penguin

I rarely read the same book twice. Because I think the only thing better than a good book is a good book you’ve never read before. But I have made exceptions a couple of times, for Mr Khaled Hosseini’s A Thousand Splendid Suns and Captain Corelli’s Mandolin by Mr Louis de Bernières. The latter also has the distinction of being the only book I read in school that I’ve returned to of my own volition – I still have my school library’s copy with other students’ notes scribbled all over the margins. The book is set on the Greek island of Cephalonia during the outbreak of WWII and follows two star-crossed lovers, the titular captain and Pelagia, who make all sorts of future plans for “after the war”. Now that I’m living through my very own outbreak of another world event, it feels apt to revisit Captain Corelli’s Mandolin for the third time, and maybe make a few plans for myself. After the pandemic, of course.

Mr Ashley Clarke, Deputy Editor

The Book Of Dust: The Secret Commonwealth by Sir Philip Pullman (2019)

Image courtesy of David Fickling Books and Penguin

To avoid giving myself a nervous breakdown by refreshing logarithmic pandemic graphs online and poring over doomsday articles, I’m trying to escape the real world through a bit of fantasy. Perhaps it’s the time I’m spending indoors playing video games and reading books, but I’ve never reverted back to my childhood more than I’m doing right now, which is maybe why I’m drawn to a book wound up with a bit of nostalgia and takes me back to a simpler time. His Dark Materials, Sir Philip’s fantastical and philosophical trilogy about armoured bears, religious fascists and daemons in parallel universes, was something I loved reading as a kid, and now, nearly two decades later, Sir Philip has written a follow-up trilogy, The Book Of Dust. (I’ve just started reading the second instalment, The Secret Commonwealth, which was published late last year.) That kind of full-circle sequel is seldom done well by authors, but Sir Philip has pulled it off, and the world he’s created in these books is just as glitteringly captivating now as it was then. Plus, there’s something soothingly familiar about reading a book so close to my childhood in a time like this. It’s something to be appreciated by all ages, and, as I’m finding out, in all scenarios, too.

Mr Jim Merrett, Chief Sub-Editor

The Amazing Adventures Of Kavalier & Clay by Mr Michael Chabon (2000)

Image courtesy of 4th Estate

Winner of the 2001 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction and noted as one of “the three great books of my generation” by no less than Mr Bret Easton Ellis*, Kavalier & Clay (for the sake of brevity; not that at 600-odd pages it is especially brief) is a book worth turning to when times are tough. Penned before the Marvel Cinematic Universe rendered comic books a multi-billion-dollar concern, this is essentially the origin story of comic books themselves. In fact, you could think of it as the bizarro version of the creation of Superman.

Set around the titular writing and illustration team, Jewish cousins brought together on the cusp of WWII when one escapes Nazi-occupied Prague for New York, the pair get swept along in the golden age of comic books. And as with Messrs Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster’s parallel Man of Steel, their hero, The Escapist, leaps from the page to become a force in the fight against fascism and the defence of freedom – but also within the internal dynamics of a booming industry that fails to reward its own talent.

While a work of fiction, the story shadows the real-life biographies of figures such as Messrs Siegel, Shuster, Stan Lee, Jack Kirby, Bob Kane and Will Eisner. Perhaps of more wider interest, it is also completely immersive, emotionally charged and includes cooking tips for the best scrambled eggs that you will ever eat, assuming you can find eggs.

*The other two were The Corrections by Mr Jonathan Franzen and The Fortress Of Solitude by Mr Jonathan Lethem, in case you had time to read them, too (and you probably do).

Mr Tom Ford, Editor

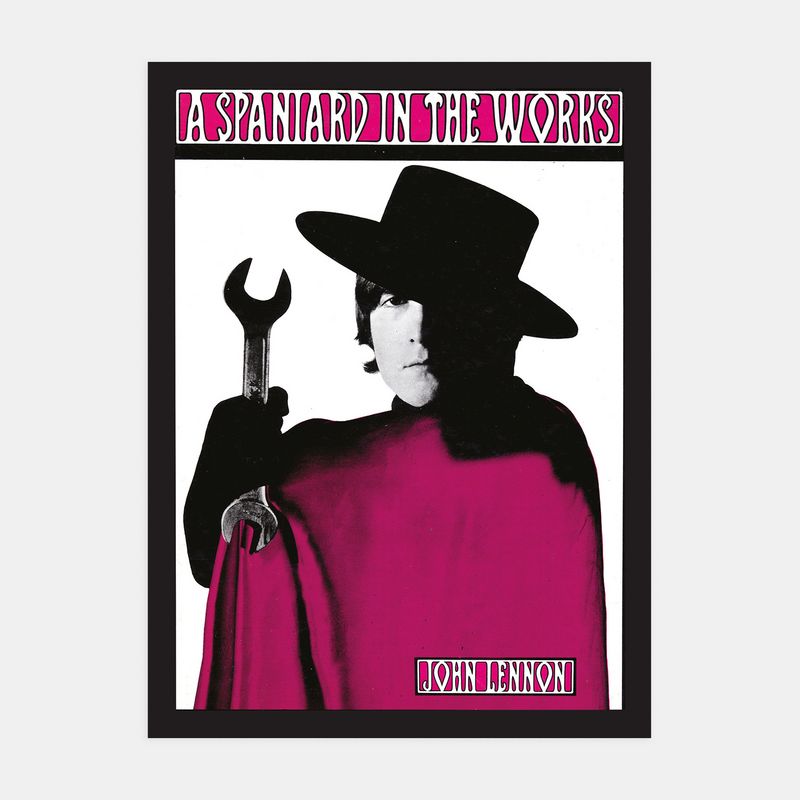

A Spaniard In The Works by Mr John Lennon (1965)

During his recent apology for breaking the self-isolation rules he had previously supported on Twitter just hours before drunkenly crashing his Range Rover into some parked cars, the footballer Mr Jack Grealish said he was looking forward to a time when “all this has boiled over”. He meant blown, of course – the diametric opposite of what he said – but it was a lovely bit of wordplay, albeit unintentional, in an already laughably unconvincing soliloquy. In my book, a bit of absurdity is a welcome tonic at the best of times, never mind when life is as strange and humdrum as it is at the moment.

And so, we move tenuously to the literary escapism of Mr John Lennon’s story collection A Spaniard In The Works – which included titles such as “Snore Wife And Some Several Dwarts” and “Araminta Ditch”. Published in 1965 as a second volume to In His Own Write, it showcased the songwriter’s flair for acerbic wordplay and caused the likes of Mr Bob Dylan to encourage him to get more nonsense into his songs. (As well as an author, Mr Lennon was also a member of a band called The Beatles, responsible for such songs as “I Am The Walrus”.) All together now: “I am the egg man/They are the egg men/I am the walrus/Goo goo g’joob.”

Mr Chris Elvidge, Marketing Editor

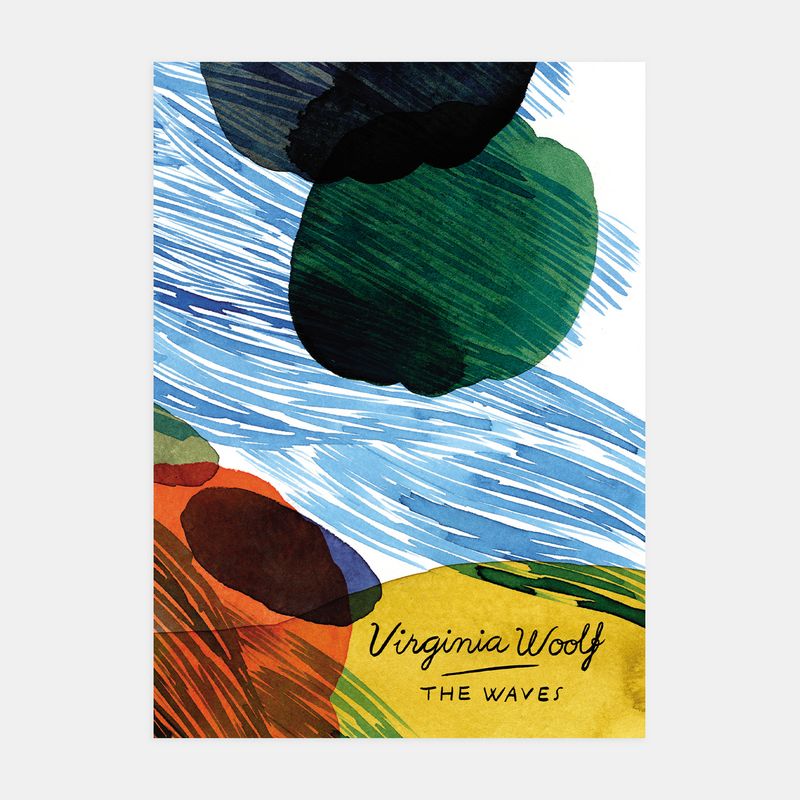

The Waves by Ms Virginia Woolf (1931)

Image courtesy of Penguin

Ms Virginia Woolf was never afraid to challenge literary convention, but The Waves is an experimental work even by her own standards. The plot, which traces the intertwined lives of six friends as they grow up, fall in love, marry, become parents and enter old age, could almost be described as conventional; but The Waves is a novel in name only, and concerns itself far less with the details of its characters’ lives than it does with conveying a sense of mood, rhythm and symbolism through its language. An almost impossibly poetic book, I first read it when I was at university and still find myself reaching for my old dog-eared paperback copy from time to time. It never fails to make me fall back in love with the English language.

Ms Lucy Kingett, Acting Content Manager

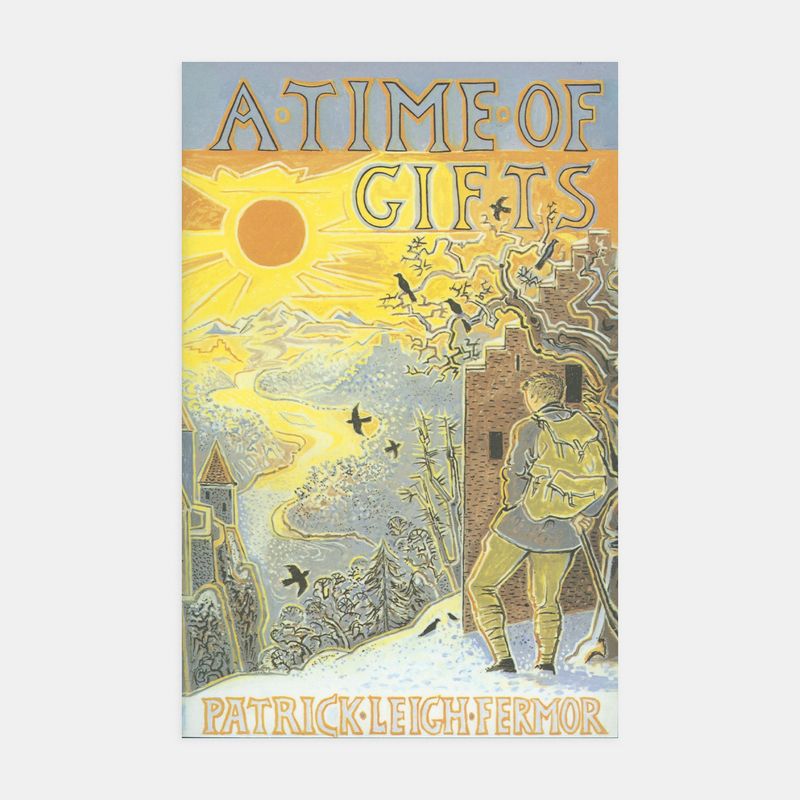

A Time Of Gifts by Sir Patrick Leigh Fermor (1977)

Image courtesy of Hodder & Stoughton

During times of stress or uncertainty, my unfailing motto is: more historical whimsy. This invariably means getting out my Poirot box set and pulling down any reading material that can whisk me off to a time in which my only concern will be which arrangement to play on the pianoforte gifted to me by Lord Mortimer. I can concede to staying in Britain and having no holidays, as long as that Britain is compiled of windswept moors and coastlines, clattering drinks parties and tight-chested romance. This might mean Mr Thomas Hardy’s Far From The Madding Crowd for a dose of pastoral charm and heavy breathing, or Ms Mary Wesley’s The Camomile Lawn if I am in want of some stiff-upper-lipped family dynamics. Mr Graham Greene gets a look in, too, when Britain is exhausted and only cigar smoke, espionage and whirring ceiling fans will do.

However, if there’s one book that tops them all, it’s Sir Patrick Leigh Fermor’s A Time Of Gifts. This is the first of three volumes that document the author’s journey on foot from the Hook of Holland to Constantinople in 1933, when he was 18. Setting off with little to his name (but plenty of connections), he sleeps in hay barns and grand castles, traces the meanderings of the Danube through steep forest and ponders (sometimes in excruciating detail) the architectural facets of monasteries. Combining the young Sir Patrick’s exuberance with the older version’s intellect and storytelling, it’s a fascinating and beautifully wrought picture of Europe and European culture just before the outbreak of war. If you’ve ever had the urge to leave everything behind and forge a new life, this might be the book that makes you do it.

Mr Adam Welch, Editorial Director

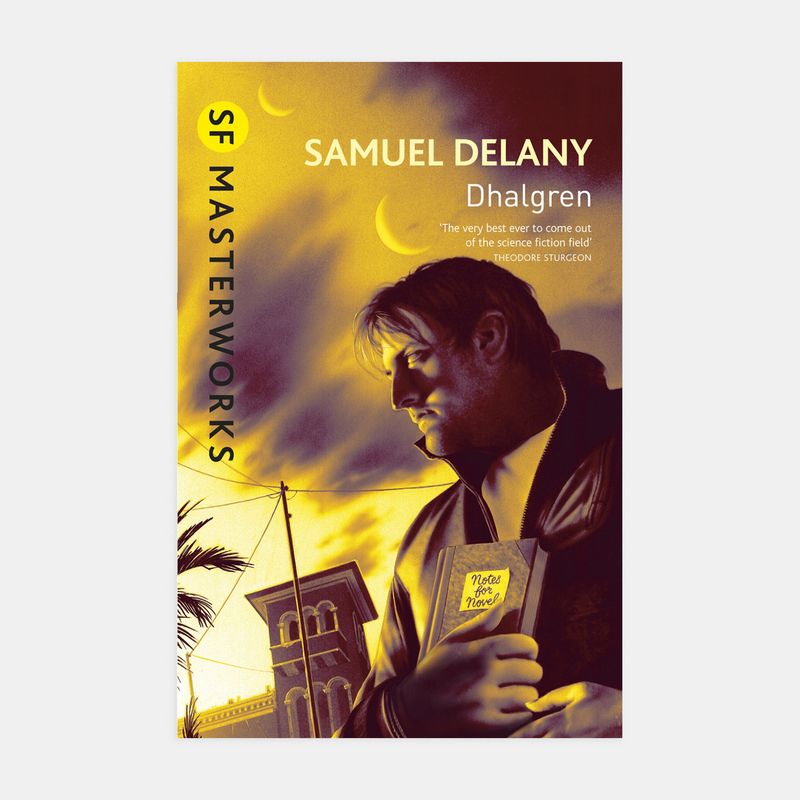

Dhalgren by Mr Samuel R Delany (1975)

Image courtesy of Orion Books

The last time I tried to read Dhalgren, the incredibly odd 1975 sci-fi masterpiece by Mr Samuel R Delany, I almost made it to the end – from page 651 it descends into a fragmented “Plague Journal” in which several different (incomplete) texts are superimposed. And at the time I thought, “Ech, I’ve got better things to do.” Now, not only do I not have better things to do (besides work), but, as I continue to jog along an empty South Bank for my daily exercise, I keep thinking about the strange world that Dhalgren presents, and want to dive back in. The book follows an anonymous protagonist, The Kid, as he arrives at the fictional US city of Bellona, which is now semi-deserted and cut off from the rest of the US following an unspecified, but dramatic event (sound familiar?). The Kid himself doesn’t appear to have many of his memories. Gangs roam the streets at night, wearing holographic projections of insects and mythological creatures. He finds a diary which appears to have fragments of Dhalgren, the book, within it. It’s been called “Joycean” – in reality, it’s hallucinatory, quite kinky and completely bonkers. All in all, a fine, and apt, challenge for these weeks in isolation.

MR MICHAEL KRUEGER, GLOBAL HEAD OF PR

Crossing To Safety by Mr Wallace Stegner (1987)

Image courtesy of Penguin Classics

My “new” reading list is usually 10-15 books deep – always a bit daunting and always overlooked. Coupled with these stressful times, I want to retreat to time-honoured comforts rather than tackling the new. Mr Wallace Stegner’s Crossing To Safety is a salve for me. It’s an enduring tale of friendship, the work of two couples’ lives, and a testament to an examined life. I’ll take a pilgrim soul’s meditation over far-out escapism any day.