THE JOURNAL

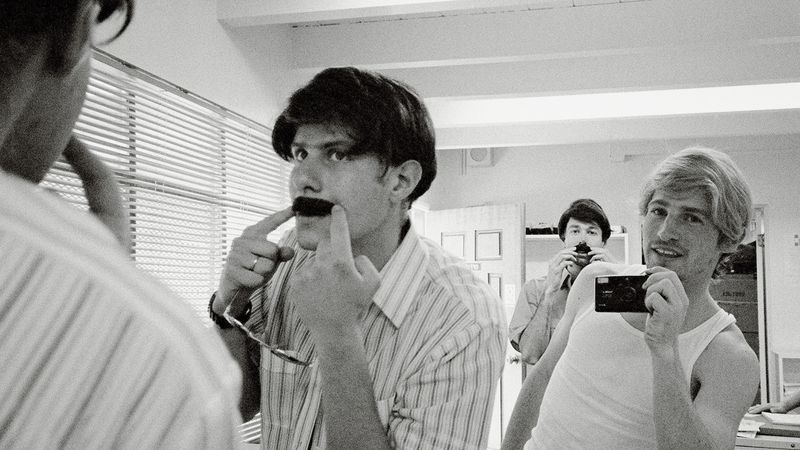

Messrs Mike Diamond, Adam Yauch and Spike Jonze prepare for the Sabotage music video in a scene from Beastie Boys Story (2020). Photograph courtesy of Apple TV+

Mr Spike Jonze’s Beastie Boys Story documentary centres upon a live show, during which two now-middle-aged men (Messrs Adam Horovitz, 53, and Michael Diamond, 54), stand on a stage in Brooklyn and talk about being members of the Beastie Boys, an early-1980s New York City hardcore band that became a rap trio and later a generation-defining cultural phenomenon. Like the stage show, which the group’s longtime coconspirator Mr Jonze also directed, the movie is goofy and self-deprecating, and unavoidably haunted by the absence of a third Beastie Boy, bassist Mr Adam Yauch, who died of salivary-gland cancer in 2012, at 47. His passing brought an end to the band, because there could be no Beastie Boys minus one of the three MCs. But also, (as the movie convincingly argues) because Mr Yauch was the group’s creative engine; the reason they moved in as many directions as they did, risked as much, evolved as quickly.

Of all the lessons the group had to teach us – from “You should sleep late, man, it’s just much easier on your constitution” to “Nothing sounds quite like an 808” – Mr Yauch’s arc from dirtbag to Buddhist artist/activist/filmmaker is the most fundamental, a reminder of the core human obligation to grow and outgrow. That he was also probably the best-dressed Beastie overall was a bonus and another way he discretely led this leaderless band.

In the film, Mr Yauch is always nailing a look, whether he’s skating in the band’s in-studio halfpipe in plaid pants and a dashiki or meeting monks backstage at the Tibetan Freedom Concert in a garment that’s probably a Fuct jacket but drapes just like the monks’ robes. In the movie, Mr Diamond tells a story about going to see Bad Brains play and meeting an impossibly hip kid in combat boots with homemade punk badges on his trench coat – the young Mr Yauch.

As downtown hardcore kids, the Beasties-to-be dressed up the buttoned-down anarchy of Black Flag’s Mr Greg Ginn – a punk-guitar-god with the shirt game of a Driver’s Ed instructor – with the occasional tam-o’-shanter. Soon, though, hip-hop came in and changed everything. After Run-DMC dropped “Sucker MCs”, Mr Horovitz says in the film, “we looked at every picture – trying to figure out their sneaks, their clothes, everything.”

Outfitted in matching shiny Puma tracksuits and questionable headgear (“Yes,” Mr Diamond acknowledges as the image brings the house down, “those are durags”), they head uptown to open at the Encore for Mr Kurtis Blow, among whose fans they make no converts. Toward the end of 2018’s Beastie Boys Book, Mr André Leon Talley offers ball-busting critique of various Beastie fits, including the tracksuit photo, insisting that the durags are not even durags, but snoods, which he somehow views as incalculably worse.

Pure store-bought appropriation of black street style made them look like dorks, of course. But, after that, barring some questionably voluminous jeans silhouettes in the mid-1990s, the Beastie Boys seldom put a foot wrong, style-wise – except for deliberate ironic effect, like when they rolled up to the 2004 MuchMusic Video Awards in bug-eye sunglasses, leather and blinged-out crucifixes, pastiches of the fashion-victim trend-heads they never, ever were.

As early as “Fight For Your Right”, the 1986 headbanger-rap hit that became an anthem and an albatross, they had signature looks dialed in, derivative of nothing in particular, from Mr Horovitz’s flipped-up Huntz Hall ball-caps and vintage phys-ed T-shirts to Mr Yauch’s black-leather Schott jacket, customarily worn over an undershirt.

Even their B-Boy flash became a means to an end: the Volkswagen hood ornament swinging from Mr Diamond’s gold rope chain was at once an upside-down joke about hippies in peace-sign necklaces, an homage to the Mercedes-Benz medallions worn by rappers, such as Mr Rakim Allah, and a winking acknowledgement of the cultural gulf between those rappers and Mr Diamond. The VW chain was also the first Beasties look to be widely emulated. Volkswagen-medallion theft surged around the world that year; one biography of Def Jam’s Mr Russell Simmons even claims the founders of the seminal trip-hop label Mo’Wax met when Mr Tim Goldsworthy sold a pilfered Volkswagen insignia to Mr James Lavelle.

During this era, the Beastie Boys toured in character as beer-throwing boors, lost themselves a little, then found themselves anew in Los Angeles – Mr Horovitz having moved out first, to try acting, met DJ/producers Mr Matt Dike and the Dust Brothers, and then sent for his partners. While making Paul’s Boutique, a psychedelic New York memory box of a rap record, the group rented a house in the Hollywood Hills, from television director Mr Alex Grasshoff and his wife, that they describe in the film as being “like a 1970s museum” and “like Hart to Hart combined with The Love Boat combined with the Regal Beagle from Three’s Company”.

In this house, a locked closet beckoned, because it was locked and the Beasties were young and often high, and proved to contain Ms Grasshoff’s collection of technicolour-dream patchwork overcoats, tailored silk overalls, wing-collar disco shirts, satin jumpsuits, fur hats and platform shoes, all of which they adopted as their own. It was the style equivalent of what they were up to in the studio – layering samples as if too much was never enough, cherry-picking the funk from unlikely sources, including Mr David Bromberg and The Eagles. Also, this being 1988 or so, they’d entered their 1970s-revival phase years ahead of 1970s phenomena of the 1990s, such as The 70s Preservation Society Presents Those Fabulous 70s, Reservoir Dogs, Dazed & Confused, Disco Stu from The Simpsons or Boogie Nights, in which Mr John C Reilly and Mr Mark Wahlberg disco-dance to the same Commodores song looped in Beastie Boys’ “Hey Ladies” in a scene indebted to that song’s extravagantly Grasshoff-closet-enhanced video.

Messrs Adam Horovitz and Mike Diamond in Beastie Boys Story (2020). Photograph courtesy of Apple TV+

The group blossomed creatively on Paul’s Boutique, but bricked commercially. Instead of touring behind a record nobody wanted to buy or continuing to spend money on high-end studio time and 1970s-mansion rental, they converted a former ballroom-dance studio on the Los Angeles/Glendale border, picked up live instruments, and made 1992’s Check Your Head. Style-wise, these were the “classic years” – ski hats, workwear, deadstock adidas and the occasional bit of thrift-store flair, such as the double-knit Irishman polo Mr Horovitz wears under a parka in the “Pass The Mic” video. They also wore a lot of flannel, aligning circumstantially with rock-fashion trends of the moment (Mr Yauch, in the film, says derisively to a reporter: “You must be talking about grunge.”)

The Beastie Boys became influencers before the word existed, curating a record label called Grand Royal and a brilliant, highly sporadic zine of the same name, whose first issue featured a fashion spread inspired by tabloid legend Mr Joey Buttafuoco (Mr Horovitz in Zubaz and Speedos) and a satirical piece assailing the Gap as “a front for global domination”. In 1991, the first X-Large store opened on Vermont Avenue in Los Feliz. Although an independent business, in which only Mr Diamond was a partner, thus not technically part of the Beasties’ own global-domination portfolio, it functioned as a de facto bastion of their aesthetic, first selling Carhartt WIP and Ben Davis workwear alongside vintage adidas, Puma and Keds, before branching out in a preppier direction befitting Mr Diamond’s raps about hitting the links in “funky fly golf gear from head to toe”.

In the Beastie Boys book, Mr Jonze writes about a turning-point visit to a fake-hair emporium with the Beasties. “So, basically,” he explains, “once we discovered wigs and moustaches, we just couldn’t stop, and we would go out in disguises every night.” This all led to 1994’s “Sabotage”, maybe their most indelible video, which sent up 1970s tough-guy masculinity while salvaging its aesthetic flavour – a useful model for all retro activity. Painstaking in its attention to period detail (minus the skater-ish way the Boys wore their plainclothes-cop suit pants), “Sabotage” hinted at another evolution to come. As the Beasties grew older, their day-to-day style mellowed, but their special-occasion looks (videos, TV performances, live shows) became about commitment to a series of playful and increasingly complex bits. Hence the new style: the Japanese-safety-worker uniforms, the head-to-toe Muppet-fur jumpsuits, the lab coats.

“Every day we were in the studio,” Mr Horovitz says in Beastie Boys Story, on the making of the instrumental album The Mix-Up, “which was five days a week, we had to be dressed in clothes only from the years 1956-1964… We went on crazy eBay shopping sprees, buying all the sharkskin suits, small-collared button-down shirts, ties and tie clips we could find… It may not be the greatest record you’ve ever heard, but we looked fuckin’ nice while making it.” Really, why be in a band at all, if not to make your self-presentation an extension of your art? Maybe an endlessly productive creative mindset begins with changing out of what Mr Horovitz, in the film, calls “your Oscar Madison clothes” – before looking down at his own, sort of shlubby, Oscar-from-The-Odd-Couple grey sweatshirt and khakis.

Beastie Boys Story_ will be available on Apple TV+ on 24 April_