THE JOURNAL

Citroën DS 19 on the quays of The River Seine, c. 1955 Edouard Boubat/ Gamma-Rapho/ Getty Images

The ultimate vehicle of the space-age turns 60 this October, but it will never be out of style.

French cultural theorist Mr Roland Barthes often crops up in literary appreciations of the Citroën DS, which debuted 60 years ago this month at the 42nd Salon de l’Automobile in Paris (it changed its name to Mondial de l'Automobile in 1988). This is because, in Mythologies – his influential 1957 collection of essays – “The New Citroën” (as he calls it) gets a whole chapter. Not many cars excite that sort of lofty intellectual curiosity, but the DS’s symbolic power was – and remains – self-evident.

Some may have missed the point of his Mr Barthes’ observations, though. The DS – Déesse (goddess) – might have looked like a spacecraft, as if it had “fallen from the sky”, but Mr Barthes also identified, within it, a more earthly quality.

“It is possible that the Déesse marks a change in the mythology of cars. Until now, the ultimate in cars belonged rather to the bestiary of power; here it becomes at once more spiritual and more object-like… one is obviously turning from an alchemy of speed to a relish of driving.”

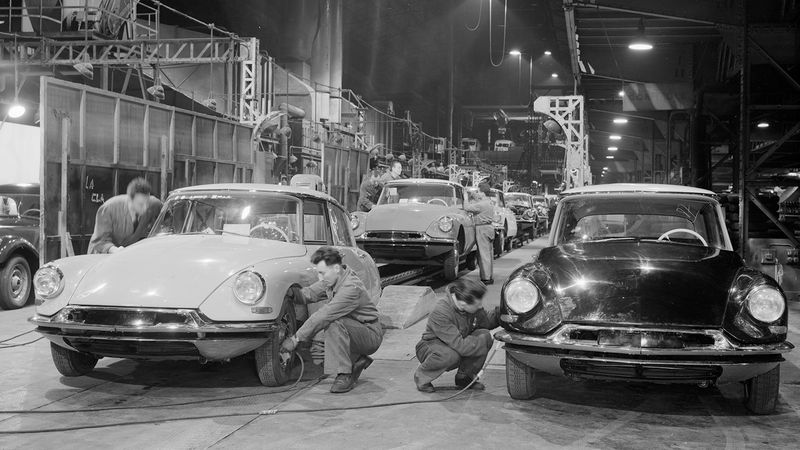

The Citroën DS assembly line at the factory in Quai de Javel, Paris, 1955 © Citroen Communication / DR

Mythologies wasn’t reprinted in English until 1972 – a year before the DS ceased production after an impressive 17-year run. If anything, the passing of time has only crystallised the Citroën’s influence and the clarity of Mr Barthes’ assessment. The original DS has transcended mere transport to become an almost philosophical statement. You didn’t need to drive it quickly to appreciate it. In fact, you didn’t need to drive it at all. Only the French could really pull off a trick like that.

The DS survives and thrives today because it is one of the last truly visionary automobiles, a tireless resister of obsolescence. Company founder Mr André Citroën was the progenitor of the innovative ethos that gave rise to it: his Citroën Type A of 1919 was Europe’s first full-production car, while his grasp of mass communication was equally far-sighted (in 1925, Citroën used 250,000 bulbs to illuminate the Eiffel Tower in an elaborate publicity campaign).

“The DS survives and thrives today because it is one of the last truly visionary automobiles, a tireless resister of obsolescence”

Mr Citroën was also a lateral thinker, a clever engineer and an explorer. In 1924 and 1925, he organised expeditions across Africa and Asia, and invited painters, film-makers, historians and scientists to participate. But renaissance figures rarely make great businessman, and when Citroën went bankrupt in 1934 after its founder, having invested everything he owned in the magnificent Traction Avant (or Light 15 that pioneered front-wheel drive and the unitary monocoque chassis), tyre manufacturer Michelin stepped in.

Exhibition of decorative arts: Citroën used 250,000 bulbs to illuminate the Eiffel Tower, Paris, 1925 Boyer/ Roger Viollet/ Getty Images

Fortunately for all concerned, new boss Mr Pierre Boulanger shared Mr Citroën’s vision. And he had two prodigious allies to call upon: designer Mr Flaminio Bertoni and engineer Mr Andre Lèfebvre. Mr Bertoni was another renaissance man: a draughtsman, architect, sculptor and stylist of uncommon vision. Mr Lèfebvre had been a racing driver and aviation engineer. Mr Boulanger instructed them to “study all the possibilities, including the impossible”, and this gloriously freestyle management approach saw Citroën follow the Light 15 with the TPV, or Très Petite Voiture, whose debut was delayed by the outbreak of war (the prototypes were literally buried to evade the Germans). It finally broke cover a decade later than intended at the 1948 Paris Motor Show – it was now known as the 2CV.

That car had been created to carry four people, a crate of eggs and a big bag of potatoes across a field at 45mph. Mr Boulanger had a grander manifesto in mind for the DS: “the world’s most beautiful, most comfortable and most advanced car… [to demonstrate] that Citroën and France could develop the ultimate vehicle”.

This might have seemed an impossible mission, yet Messrs Bertoni and Lèfebvre joined forces with spectacular effect. Mr Bertoni created a body that somehow managed to be modernist, futuristic and elegant at the same time, a European riposte to the rocketry and space obsession that had gripped the car industry on the other side of the Atlantic. The DS wasn’t a gimmick, it was a vision, and the impact it made at that Paris expo is incontestable. It’s said that Citroën took 750 orders in the first 45 minutes, and in excess of 12,000 by the end of the first day.

The Citroën DS on display at the Paris Motor Show, October 1955 © Citroën Communication / DR

The DS was as much a technical tour de force as it was a visual one. These were cars that exemplified the idea of travel above all else, and the DS’s rolling comfort was outstanding. Key to this was the car’s clever and complicated “hydropneumatic” self-levelling suspension, thats hydraulic pump and gas-filled spheres allowed the DS to sink so low that its bodywork almost enveloped its wheels, and, at the other extreme, ride high to traverse badly rutted surfaces. In between, it simply glides along. Famously, French President Mr Charles de Gaulle was able to escape a 1962 assassination attempt because his DS’s suspension ensured that it remained driveable even with punctured tyres.

“The DS was a cultural leap towards the future that industry and society were experiencing at that time”

Its pillow-like ride quality is only part of the DS’s otherworldly and life-preserving behaviour though. The steering is so light that at first it feels as though the wheel – a minimalist single-spoke item and another Mr Bertoni flourish – isn’t connected to the front wheels at all. The braking system is also disconcerting: rather than a conventional pedal, you push a large rubber button, and even a gentle prod is enough to stand the car inelegantly on its elegant nose. In addition, the DS was the first mass-produced car with front disc brakes, although it was some years before it received an engine to match the rest of it.

More than 1.5 million DS models were sold during its lifespan and the hugely rare Decapotable – the work of French coachbuilder Mr Henri Chapron – is the most desired and valuable. The car evokes a fabulous pop-cultural era as perfectly as Mr Jean-Paul Belmondo and Ms Jean Seberg in Mr Jean-Luc Godard’s 1960 film À bout de souffle. Unsurprisingly, it still inspires the world’s top automotive designers today.

The Champs Elysées Citroën store, November, 1959 © Citroen Communication / DR

“Sublime,” Jaguar’s design director Mr Ian Callum says. “Citroën presented the car at one point without its wheels, which was an unbelievably audacious thing to do. It looked like it was flying. Funnily enough, I saw a wooden buck of the E-type once, with no wheels. The DS and the E-type are probably the only two cars I can think of that look as good without their wheels…”

Ferrari’s director of design Flavio Manzoni – a trained architect and a man with a peerless aesthetic – is clear about the car’s place in the automobile pantheon.

‘The DS was a huge cultural leap, and emblematic of the momentum towards the future that industry and society were experiencing at that time. The postwar period was very fruitful, they were the years of great initiative, innovation and creativity.

“But what struck me most was that the car seemed equipped with its own life. As a young boy, when I saw one starting up and gradually detaching from the ground, it seemed to me that it was awakening, switching from a resting state to an active one and literally coming to life. One had the impression of being in front of the future, with all its best promises.”

The Citroën DS, September 1962 ullstein bild via Getty Images