THE JOURNAL

Mr Eddie Murphy at the premiere of Boomerang, Los Angeles, June 1992. Photograph by BEImages/Shutterstock

As with many aspects of 2020, Movember – that 30-day challenge to grow a moustache while raising money for and awareness of men’s mental and physical wellbeing – will be a bit different this year. The event reported some 400,000 participants last year, and many more will no doubt join in this November, too. But this time around, it might feel like more than a monthlong fling.

Like the hat and, increasingly, the tie, the moustache can be easily dismissed as an affectation of a man’s appearance that belongs to another time. From the stiff upper lips of the world wars to the vast handlebars of the 1970s, the moustache’s best days are seemingly behind us. Indeed, its relative scarcity is part of the reason it became the emblem of Movember – plucked from obscurity, if you will.

“When Movember started back in 2003, the moustache had all but disappeared from fashion trends,” says Mr Justin Coghlan, the co-founder of the Movember Foundation. He notes that, back then, “the mo’ still had the ability to turn heads and generate conversations”. And it still does, of course, but in 2020, it has taken on a more modish quality.

With many of us confined to our own homes earlier this year and social media becoming our only link with the outside world, the moustache found itself thrust into the spotlight once again. Grown as a point of interest for Zoom calls, something to hide under a mask or simply experimental, facial hair became more commonplace. And with time on their hands and no red-carpet events to attend, even modern-day style icons – including the likes of Messrs Harry Styles, Timothée Chalamet and Tyler, the Creator – could be seen sporting a “lockdown ’tache”.

The desire to reinvent our image often went deeper than follicle coverage on our top lip, of course. This year has forced us to reflect on ourselves and our place in the world. Not that soul-searching and growing a moustache are mutually exclusive activities; Pulitzer Prize-winning New York Times journalist Mr Wesley Morris managed both, as his magnificent tour de force on his own facial hair, interwoven with Black American history testifies (the accompanying ’tache was pretty top drawer, too). Touching on figures of the civil rights movement through to Carlton from The Fresh Prince Of Bel-Air, he considers the moustache “a dignified symbol in the pursuit of equality”, employed by those trying to unify rather than disrupt (Dr Martin Luther King Jr, notably, took great care of his). “On a Black man, it signified values: perseverance, seriousness, rigor,” he concludes. “But there was nothing inherently Black about it. A [moustache] meant business. An Afro meant power.”

That said, there is no doubt that in the right hands – or, rather, perched on the right lip – a moustache can be a potent force. “One dream, one soul, one prize, one goal, one golden glance of what should be,” Mr Freddie Mercury sings in Queen’s 1986 hit “A Kind Of Magic”. Anyone who has sat through the official biopic or numerous BBC Four documentaries knows how the band came into being, but there’s no doubt that Mr Mercury’s moustache – his most notable look – was the making of the man. Likewise, you’d be hard placed to picture the likes of Sir Charlie Chaplin or Mr Eddie Murphy, Mr Salvador Dalí or Mr Stan Lee entirely clean-shaven. A moustache is part of their identity. But what about us mere mortals?

“In a world where beards are ubiquitous, a moustache is a much stronger style statement”

“I’ve tried sporting a moustache several times,” says grooming expert Mr Lee Kynaston. “On each occasion, I’ve concluded that it just doesn’t suit me. But I think it’s always worth giving it a go because for every person it doesn’t suit, there’s one whose face was born for it. And in a world where beards are ubiquitous, a moustache is a much stronger style statement.”

For Mr Kynaston, the rich lineage behind the moustache might actually be part of what is holding it back. “I think moustaches lost their allure in the 1970s when they became a kind of shorthand for hyper masculinity,” he says. “Think Tom Selleck, Burt Reynolds and the ‘Leatherman’ from The Village People. The thick, yard-brush ones in particular became an object of derision. The fact that it’s been the facial hair of choice for tyrants and dictators (Hitler, Stalin, Saddam, Mugabe) hasn’t exactly enhanced its reputation.

“And then there’s Movember,” he adds. “Now, I love Movember – it has done more for men’s causes than any initiative I can think of.” However, he fears that, as a result of this good work, growing a moustache can today be viewed as “a bit of a novelty” rather than a long-term grooming choice – “something men did to entertain their co-workers once a year”.

If Mr Kynaston’s concern is that the ’tache has become a comedy prop used to highlight serious issues, perhaps he didn’t need to worry in 2020. Now you’re more likely to see one on Mr Armie Hammer than a Ron Burgundy. But even those worn with the best of intentions aren’t inherently good – a great moustache takes effort.

“Moustaches will never be as popular as beards because, like skinny jeans, they’re that much harder to carry off,” Mr Kynaston says. “To grow a proper Tom Selleck, for example, you need a decent-sized philtrum (the gap between nose and lip).”

“Choosing the right style of mo’ to grace your face is key,” says Mr Coghlan. “Whether you settle on the wisp, the trucker or the businessman, go with whatever suits you. Once you’ve got past the itchy phase, maintenance is key. Be sure to groom regularly to keep it looking sharp.”

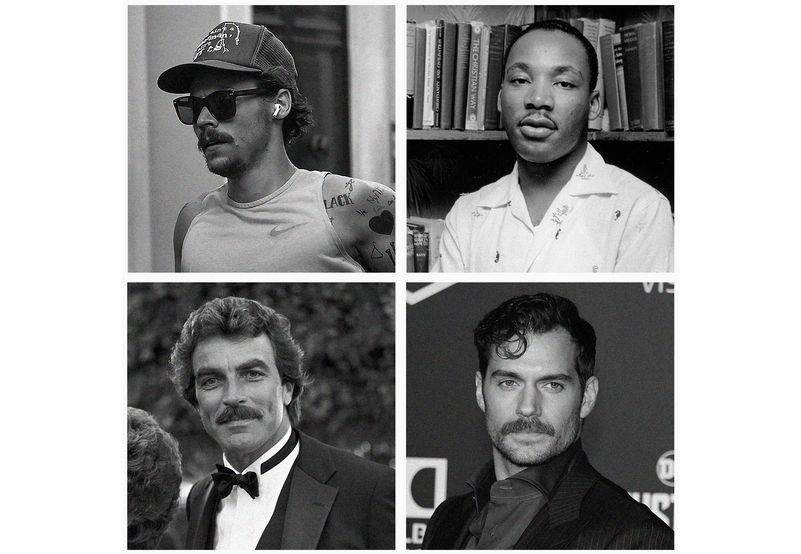

Clockwise from top left: Mr Harry Styles, Rome, July 2020. Photograph by The Mega Agency. Dr Martin Luther King Jr, Alabama, May 1956. Photograph by Mr Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images. Mr Henry Cavill, Los Angeles, November 2017. Photograph by Arpega/WENN. Mr Tom Selleck, Los Angeles, April 1983. Photograph by Mr Bob Riha Jr/Getty Images

“You need the right gear for them to look their best,” Mr Kynaston says. “A wax or beard balm to style, a comb to distribute the wax and to straighten hairs, and facial-hair scissors to keep things neat. I’d also recommend arming yourself with a transparent shaving oil, which will allow you to see where you’re shaving, so you can navigate your razor around your moustache with greater precision.

“If it’s your first attempt, play it safe and end your moustache in line with where your lips meet or a fraction beyond. Keep the edges trimmed and always trim when dry – wet hair shrinks as it dries, which may leave your moustache shorter than you intended. Since facial hair wicks moisture away from the skin, leaving it dry and flaky, massage a moisturiser or beard oil into the skin to ensure it stays properly moisturised. If you end up keep it beyond November, think about getting a professional trim and shaping whenever you have your hair cut.”

While more than a joke at the wearer’s expense, Mr Kynaston agrees it pays not to be too po-faced about sporting one. “Most importantly, have fun,” he says. “Try a handlebar (it worked for Nick Cave), a Henry Cavill-style yard brush or, hey, even a John Waters-inspired pencil number. The Mugabe is probably best avoided.”

As with anything that can have such a dramatic impact on a man’s appearance, our relationship with the moustache is complicated. Previously an emblem of virility, it is now tied to an awareness of our fallibility, and an acceptance that that is very much OK. It can be something we try for a while or find we can’t be ourselves without. On the face of it, it can be an affectation we poke fun at. But it has now come to symbolise something more: personal growth.

Mr Kynaston goes as far as comparing cultivating a moustache to “raising a child”. “You never quite know how they’ll turn out until they’re fully grown,” he says. “But that’s part of the fun, right?”