THE JOURNAL

Messrs Timothy Behrens, Lucian Freud, Francis Bacon, Frank Auerbach and Michael Andrews, having lunch at Wheeler’s Restaurant in Soho, London, 1963. Photograph by The John Deakin Archive/Getty Images

The effortless style of this gang of louche, mid-century artists provided the starting point for our first Mr. P collection.

It was the American-born artist Mr RB Kitaj who in 1976 coined the term “School of London” to describe the figurative artists who were the true stars of post-war British painting. For Mr Timothy Behrens, though: “The School of London never existed. We were just a group of guys who got together [in Soho]… to drink. Simple as that.”

Mr Behrens was right – in a way. He and Messrs Francis Bacon, Michael Andrews, Lucian Freud and Frank Auerbach did share a great fondness for The Colony Room, Ms Muriel Belcher’s louche Dean Street drinking den, and for Wheeler’s fish restaurant in Old Compton Street, as evidenced in the photograph above. Mr Bacon had seemingly endless credit in both establishments and finally paid off Mr Bernard Walsh, Wheeler’s owner, with a portrait of the affable restaurateur. Mr Walsh had hoped for a racehorse, didn’t like the picture and sold it for £17,000.

But Messrs Bacon et al were first and foremost artists: artists who lit upon a bomb-shattered London in the aftermath of WWII and used figurative art and radical brushwork to confront the all too recently experienced horrors of the human condition. As the artist and critic Mr Lawrence Gowing noted, “The later 1940s were no time for fantasy.” And for Mr Auerbach, whose parents were murdered in the Holocaust, “There was a curious feeling that we were all naked, bare-forked animals together, people who had survived the war.” No wonder Mr Bacon regarded abstract art as mere “decoration”. So he and his friends worked hard and played hard. As Mr Auerbach also observed, “It was sexy, in a way, this semi-destroyed London.”

It is here in the back streets of Soho, and artists’ studios of post-war London that we began our search for inspiration for Mr P.’s first collection. With their loose and easy style, the School of London weren’t known their tailoring. Far from it. But by not particularly caring and carelessly throwing together corduroys, slacks and cotton shirts with no real regard for a perfect fit, the looks of Messrs Bacon, Andrews, Auerbach et al evolved into what you might call the artist’s silhouette. By no means the backbone of this collection, but a springboard, nonetheless.

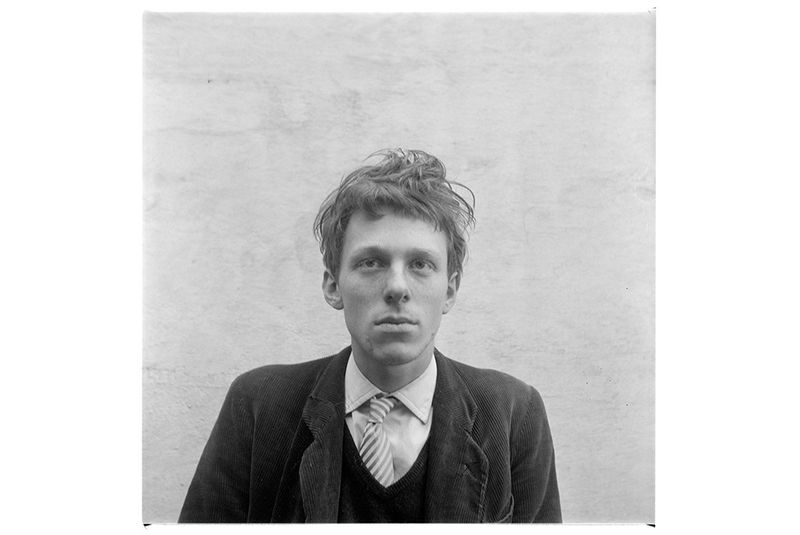

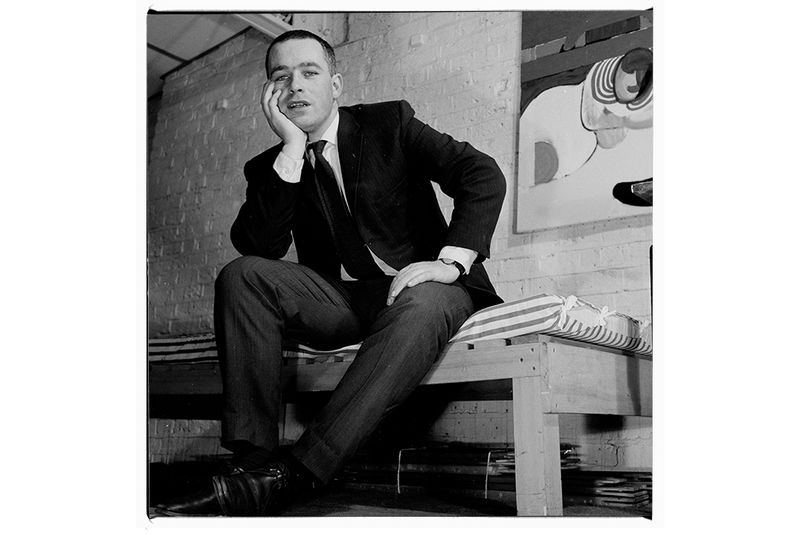

Mr Timothy Behrens

Mr Timothy Behrens at home in Britain, early 1960s. Photograph by The John Deakin Archive/Getty Images

For Mr Behrens, Soho in the 1950s was a “school of ideas” – a school he diligently attended with his close friend Mr Lucian Freud. Born in 1937, the red-haired Mr Behrens had been taught by Mr Freud and the two saw each other almost daily for nine years, at one stage sharing a flat. They also shared a taste in women; three of Mr Behrens’s girlfriends later became Mr Freud’s. Later, Mr Freud dropped him, viciously.

Mr Behrens was the son of a banker, whom he loathed, and went to Eton, which he also loathed. At 16, he took his portfolio to the Slade School of Art; he became its youngest pupil. Despite having three one-man shows in London in the late 1950s and early 1960s, he quit the city and oils to live in Italy and use acrylic paint. This was not a success, any more than his first marriage – an elopement – had been. He married twice more, moving eventually to Galicia, Spain. There, his studio was known as “the bullring”. He kept his prices low because “it disgusts me that a painting can cost more than a house”. Nonetheless, a portrait Mr Freud painted of him in between 1962 and 1963 – “Red Haired Man In A Chair” – sold for £4.15m in 2005. Mr Behrens was not impressed. “Lucian wasn’t good,” he said, “and he knew himself he was a pedantic painter. I always preferred Bacon and especially Michael Andrews.” He died in 2017.

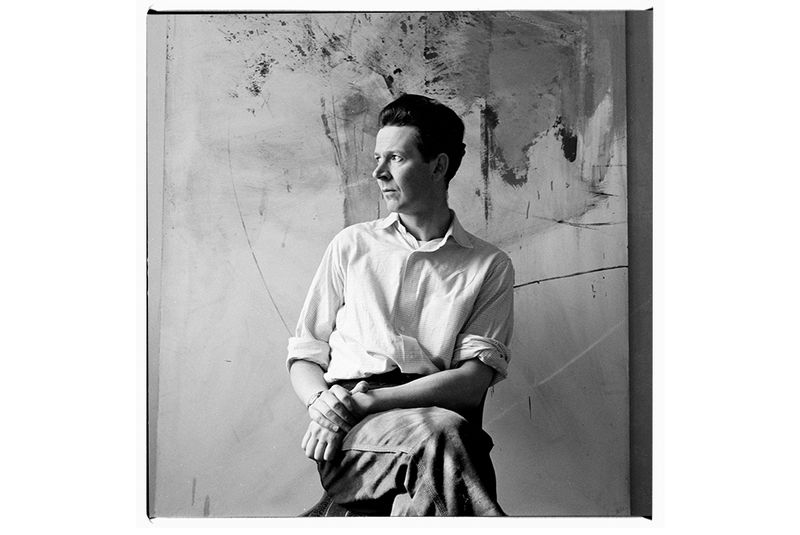

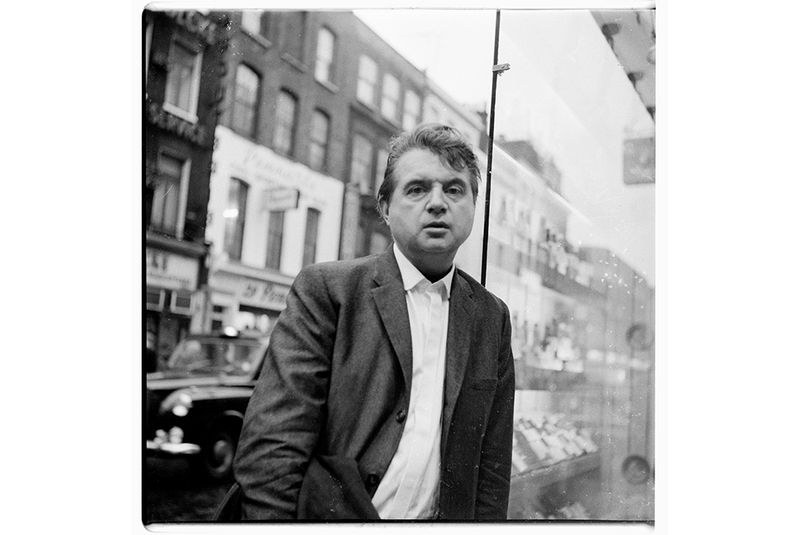

Mr Michael Andrews

Mr Michael Andrews in his London studio, late 1950s. Photograph by The John Deakin Archive/Getty Images

“Wide-eyed and popular with everyone”, Mr Michael Andrews was once seen as the forgotten man of British art – in 1974, a former director of the Tate wrote that the then 46-year-old Mr Andrews was “in danger of being taken for a rumour rather than a person”. A 2017 show in London reaffirmed his importance.

Most famous for “Melanie And Me Swimming” (1978-1979), Mr Andrews painted both a mural for Ms Belcher’s Colony Room in 1959 and a 1962 figurative picture of the club and its denizens, which was bought by the Tate. Also much admired is another “party” scene, “The Deer Park” (1962), which incorporated pop and media imagery.

The son of devout Methodists, the Norfolk-born Mr Andrews attended the Slade from 1949 to 1953, and was tutored by Mr Lucian Freud. Mr Andrews met his future wife at a party Mr Freud gave. In turn, Mr Freud often spent Christmas Day with the Andrews family, insisting on watching The Wizard of Oz. “It got to the point I hated it,” Mr Andrews’ daughter recalls. “I still do.”

Later, Mr Andrews turned to mixing water and acrylic paint in a spray gun and with them created dreamlike yet realistic landscapes. No surprise, perhaps, for a man who in the 1950s appeared in two films, playing first Mr Franz Kafka and then one of a pair of deaf mutes. He died of cancer in 1995.

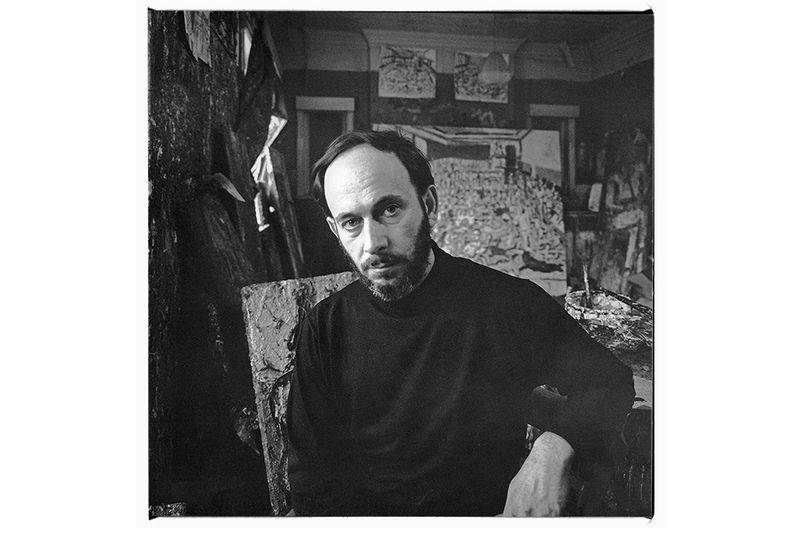

Mr Leon Kossoff

Mr Leon Kossoff, 1972. Photograph by Mr Mark Gerson/Bridgeman Images

Cool as he looks, Mr Leon Kossoff is not the sort to be photographed at glossy parties – and he certainly does not appear in Mr Michael Andrews’s picture of the Colony Room. Instead, it’s been said that “he provides so much unrestricted access to such massive amounts of spiritual discomfort that you marvel at its starkness”. That’s not always so: there can be joy to his colour.

The now 90-year-old Mr Kossoff’s family was, he has said, “absolutely not” artistic, yet as a youth he found himself drawn to the National Gallery: “it was as if the streets of the city must have led me”. So, after military service with the 2nd Battalion Jewish Brigade, he trained at Central St Martins and, together with his friend Mr Frank Auerbach, took evening lessons from the influential Mr David Bomberg.

Like Mr Auerbach, he employs very thick impasto paint and expressive brushwork. Again like Mr Auerbach, his portraits take many sittings to complete: in some, his sitter is asleep – he paints what he sees. London born and bred, the city and its people have been Mr Kossoff’s ever-nourishing fascination. Much-visited themes include the “awful, but also rather beautiful” destruction of post-war London, Kilburn Underground Station, indoor swimming pools, and, in the summer of the 2012 London Olympics, the East End area where he went to school. Returning there was, he said, “a miracle”.

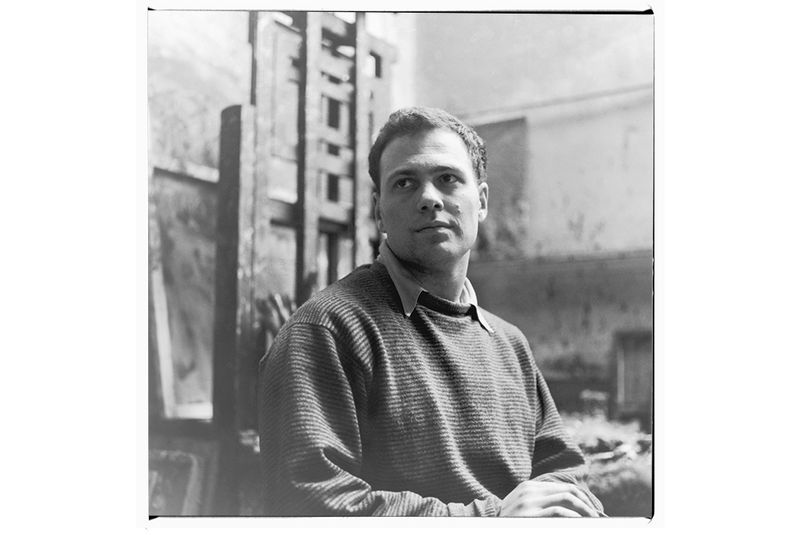

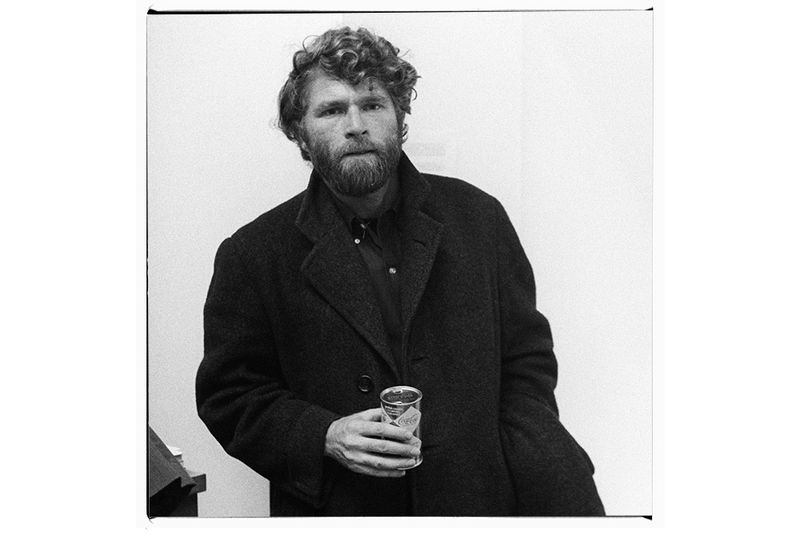

Mr Frank Auerbach

Mr Frank Auerbach in his studio in Camden, London, 1962. Photograph by Daily Express/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

“The thickest paintings one is ever likely to see,” one critic wrote of Mr Frank Auerbach’s show in 1956 – and it was, wrote Mr David Sylvester, “the most exciting and impressive first one-man show by an English painter since Francis Bacon in 1949”. Mr Bacon himself rang the Marlborough Gallery to say there was a brilliant artist, so poor that he lived on potatoes and yoghurt, whom they must sign up at once.

Mr Auerbach was eight-years-old when he was sent to England in 1939 by his German-Jewish parents; he never saw them again. At 16, he left school, determined to be an artist; St Martin’s accepted him. He became close to Mr Lucian Freud, who left his collection of 15 paintings and 29 drawings by Mr Auerbach to the nation; he also ate at Wheeler’s.

With his cityscapes of the 1950s and early 1960s, one critic noted that he “painted people as fly-eaten living corpses unforgivably surviving in a blasted world”. And he produced heavily encrusted portraits, particularly of Ms Stella West, his lover for 23 years. “It was quite an ordeal,” Ms West recalled, “because he would spend hours on something and the next time he would scrape it all off and start again. That upset me terribly.”

It’s how he has worked all his life. Until recently, he spent seven days and five nights a week in the studio he inherited from Mr Leon Kossoff and would take only one day’s holiday a year. How right Mr Sylvester was to identify in Mr Auerbach “the qualities that make for greatness in a painter – fearlessness; a profound originality; a total absorption in what obsesses him; and, above all, a certain gravity and authority in his forms and colours”.

Sir Howard Hodgkin

Sir Howard Hodgkin, 1964. Photograph by The Jorge Lewinski Archive at Chatsworth/Bridgeman Images

“I work on an enormous number of pieces at once,” Sir Howard Hodgkin noted. “I suppose it’s a fear of being unable to work.” This meant that a painting could take him more than a decade. The results, however, were “sheer colour bliss”, as Ms Susan Sontag put it.

Sir Howard, who died this year aged 84, decided to be a painter at five, when he produced a picture of a woman with a red face and bushy hair. After Eton – from which he ran away – and Camberwell School of Art, he taught and painted, claiming to be a figurative painter, which might surprise those who see what appear to be gloriously coloured abstractions. “I am,” he said, “a representational painter, but not a painter of appearances. I paint representational pictures of emotional situations.”

A sensitive man, he burst into tears when the writer Ms Lynn Barber, who was also a friend, criticised the titles he gave to paintings – “In Tangier”, “Close Up”, “Strictly Personal”, etc. “My titles are my pictures,” he said. Sir Howard did not have his first solo show until he was 30, in 1962. By 1984, he was representing Britain at the Venice Biennale; and in 1985, he won the Turner Prize. He painted till the end. “The older I get, the more dissatisfied with my work I become,” he said in 2016. “It’s a very lonely occupation – I wouldn’t recommend it to anyone.”

Mr Francis Bacon

Mr Francis Bacon on Old Compton Street, Soho, London, circa 1953. Photograph by The John Deakin Archive/Getty Images

“Champagne for my real friends, real pain for my sham friends,” Mr Francis Bacon would cry. He meant it: Mr David Sylvester wrote that he was “never rude unintentionally”. Born in 1909, Mr Bacon did not start painting seriously till his late thirties. Nonetheless, his name was made when he showed “Three Studies For Figures At The Base Of A Crucifixion” in London in 1945. Its agonised, distorted semi-humans prompted “total consternation”, a critic wrote. Screaming popes, naked wrestlers and sombre, twisted portraits followed, many using photographs as source material. From 1947, he painted in oils directly onto unprimed canvas.

The son of an Anglo-Irish racehorse trainer, he was banished from home at 17, after sleeping with several of the grooms and being caught wearing his mother’s underwear. He made for London, then Berlin and Paris before returning to London several years later. He drank hard, gambled recklessly and worked intensely. According to his biographer (and fellow-drinker), Mr Dan Farson, “He worked from six in the morning with the fierce concentration of a hangover, which had the advantage of excluding all distraction.”

His hair was “carefully disheveled” and “of variable colour” and he would usually wear a black leather jacket. It lent him a fitting toughness: as he said, “I have always thought of friendship as where two people tear each other apart. That way you learn something from each other.” Perhaps it was one such fight that led to the end of his bond with Mr Lucian Freud. Both men emanated a dangerous glamour, and both cared not a fig for conventional morality. Mr Bacon died in 1992.

Mr RB Kitaj

Mr RB Kitaj at the opening of Mr David Hockney’s show at the Kasmin Gallery, London, 1969. Photograph by Mr Homer Sykes

A latecomer to the British painting party, Mr RB Kitaj was born in Chagrin Falls, Ohio, in 1932, and reached the Ruskin School in Oxford in 1958. A brilliant draughtsman, he had his first one-man show at the Marlborough in 1963, after a spell at the Royal College of Art, where he became a lifelong friend of Mr David Hockney. He and Mr Hockney later led a campaign for a return of the study of the human figure in art schools.

Initially associated with pop art, he turned to the figurative, and it was the figurative he lauded in the catalogue for a 1976 exhibition, The Human Clay, highlighting the work of Messrs Bacon, Andrews, Auerbach et al. (Messrs Hockney, Freud and Auerbach can be seen among the guests in Mr Kitaj’s “The Wedding”, painted between 1989 and 1993, which celebrated his marriage to the artist, Ms Sandra Fisher.)

Ferociously well-read, he attached long, name-packed captions to the work he showed at his 1994 Tate retrospective. He was savaged by the London critics, and the criticism coincided with the death of his mother, at whose US bedside he was when he learned of the death of Ms Fisher, from a brain aneurysm. “My enemies,” he said, “intended to hurt me, but they got her instead.”

Acutely conscious of his Jewish identity, he revered Mr Franz Kafka; the building at the back of his “If Not, Not” (1975-1976) is the gatehouse to Auschwitz. Suffering from Parkinson’s, he took his own life in 2007.