THE JOURNAL

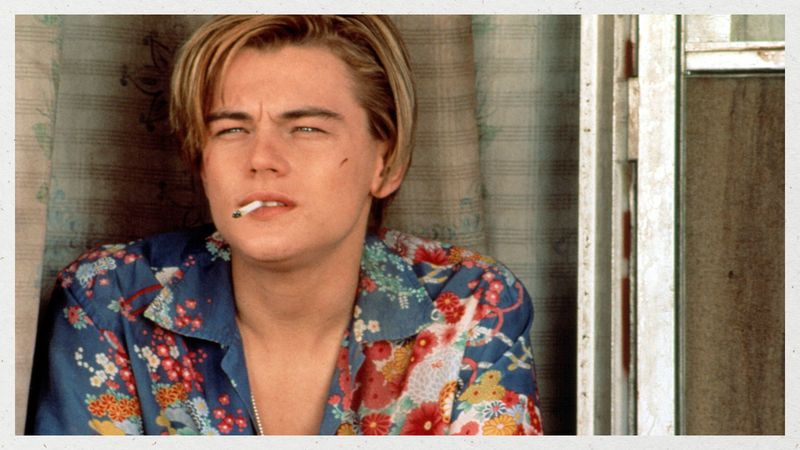

Mr Leonardo DiCaprio in Romeo + Juliet (1996). Photograph by Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation/Alamy

When Mr Baz Luhrmann released his vampy, trigger-happy Romeo + Juliet in 1996, he inadvertently posed a troublesome question: are Hawaiian shirts cool again? They’d had a moment in the sun in the 1960s after the swivel-hipped king of rock ‘n’ roll Mr Elvis Presley donned one for the cover of his Blue Hawaii soundtrack album, but by the time the 1980s rolled around, they were becoming the preserve of middle-aged tourists. Oh, and Mr Tom Selleck in Magnum, PI. And yet, here was a curtain-haired Mr Leonardo DiCaprio, along with the rest of the Montagues, surveying Verona Beach dressed in this jaunty little number.

If the bold floral shirt worn by Mr DiCaprio looks familiar to followers of fashion, it might be because Palm Angels, one of the newer members of the streetwear hegemony, produced a version for its SS20 show. As industry warden Instagram account @dietprada pointed out at the time, aping the aloha shirt – the preferred terminology in its country of origin – is hardly news. Prada’s SS14 “Menacing Paradise” menswear collection featured a reimagining of one of the most famous iterations of the garment – Mr Montgomery Clift’s palm tree-patterned shirt from 1953’s From Here To Eternity – and boxy, tropical shirts have become one of the label’s most recognisable designs in the years since.

While Romeo’s silk number, Palm Angels’ copy and Prada’s catalogue of printed shirts are certainly Hawaiian shirt-adjacent, they’re not bona fide aloha shirts. “A real aloha shirt has several things: a Hawaiian print, coconut buttons and a label that says, ‘Made in Hawaii’,” explains Mr Dale Hope, who inherited his father’s clothing business in Honolulu and later wrote the book The Aloha Shirt: Spirit Of The Islands. It didn’t necessarily start out that way, though, he adds. While Mr Ellery Chun, a Yale graduate from the Hawaiian capital, is credited with trademarking the aloha shirt in 1936, divining its true genesis is a tad trickier, and there are many – perhaps fabricated, sometimes contradictory – anecdotal tales about how it came to be.

Some say Hollywood actor Mr John Barrymore kicked things off in the early 1930s when he asked the tailor Musa-Shiya the Shirtmaker to rustle him up a short-sleeved variety using printed rather than plain Japanese kabe crepe fabric intended for kimonos; others point to a group of local schoolboys who commissioned matching shirts to wear to a summer gala. “Nobody has been able to document that story,” says Dr Linda Bradley, a professor of the history of dress and the author of numerous books on aloha attire (including one that served as the source material for that Prada show).

What is certain, however, is that the aloha shirt wouldn’t have materialised if it hadn’t been for Hawaii’s diverse cultural makeup, a product of rapid immigration to the islands during the mid-19th century. “They [US landowners in Hawaii] had to import labour from Asia to run the plantations,” Dr Bradley explains. “The aloha shirt draws from five different ethnic groups,” she adds. “So, you had Japanese fabric, you had Chinese tailors to create things [and] you had the Western notion of a shirt.” Wearing it untucked was borrowed from the Filipino population, who wore lightweight barong tagalog tunics in the sugar fields. “What makes it Hawaiian is when, by the 1930s, they started printing their own fabrics instead of relying on fabrics which were brought into the islands,” Dr Bradley says.

The cloth and prints are the perfect canvas to tell the stories of Hawaii. Whether you’re telling stories of the landscape or tales of the flora

The attack on Pearl Harbour in 1941 – right around the time production of the aloha shirt ramped up to cater to a growing military presence on the island – also saw Japanese prints fall out of favour, says Dr Bradley. “Instead of Mount Fuji, they put in Diamond Head; instead of the carp, they put in our mahi-mahi, marlin and swordfish; instead of cherry blossom, they used our hibiscus and ginger,” says Mr Hope. “The cloth and prints are the perfect canvas to tell the stories of Hawaii. Whether you’re telling stories of the landscape or tales of the flora – the breadfruit, coconut, flowers – or surfing, canoeing, paddling and fishing. All these stories are communicated on the fabric of the aloha shirt,” he explains. And when US soldiers stationed in Honolulu or sent there for R&R came home to the mainland dressed in lush prints that promoted Hawaii as the ultimate vacation destination, it caught on.

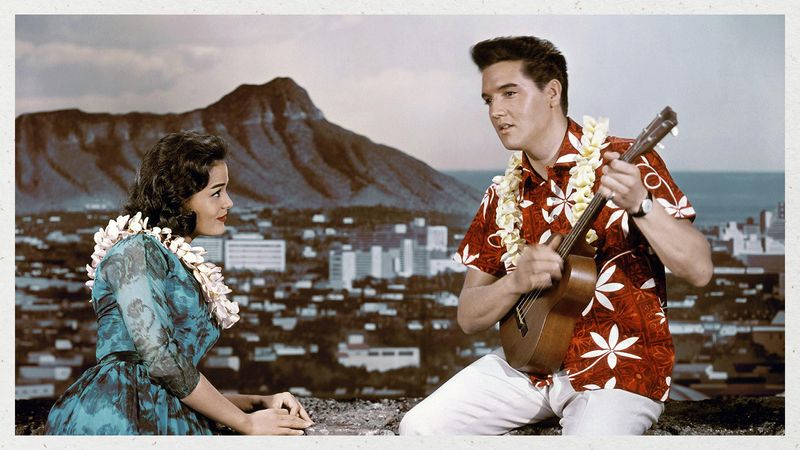

The romantic tale they told of laid-back island living appealed to the buttoned-up American middle class. “Take it easy,” said one ad for aloha shirts from the time; “Not a shirt, a way of life,” read another. The aloha shirt became a passport to paradise and, happily, air travel was becoming more and more affordable for a generation who, having witnessed two world wars and the Great Depression, were primed for some rest and relaxation themselves. It helped matters, of course, that some of Hollywood’s brightest stars – the aforementioned Mr Presley and Mr Frank Sinatra, to name just two – were busy modelling the aloha shirt on the silver screen, while a grinning President Harry S Truman proudly wore his on the cover of Life magazine.

Ms Joan Blackman and Mr Elvis Presley in Blue Hawaii, 1962. Photograph by Paramount Pictures/Alamy

By the 1960s, it seemed the only people not wearing aloha shirts in Hawaii were Hawaiians. “It became marketed as a souvenir,” Dr Bradley explains. “[The locals] didn’t like those bright, bold colours. They dressed very much like people on the mainland – long-sleeved white shirts, sometimes even ties,” she says. To capitalise on the promotional potential of the aloha shirt, then, the legislature came up with a plan: Aloha Fridays – one day a week where white-collar workers were encouraged to adopt the unofficial national dress. “It wasn’t an overnight slam dunk,” explains Mr Hope of the initiative introduced in 1965. “It took years before everybody relaxed enough to say ‘OK, aloha shirts are OK for the summer’”. But, eventually, it hit the mainstream. “As soon as people got over the idea that you have to wear a buttoned-up white shirt to be considered respectable, they were accepted. And the aloha shirt became the standard dress for Hawaiian men from that point on, in the late 1960s to the present,” says Dr Bradley.

Fashion’s history books will tell you that hoodie-wearing Silicon Valley execs are the reason why you’re unlikely to get fired for wearing sneakers to the office these days. Though, it would seem, the origins of dressing down for work is a little more nuanced than that. “In the 1960s, a lot of kids from Southern California came into Hawaii to learn to surf. And you can’t be a good surfer without an aloha shirt,” posits Dr Bradley. When they came home, as well as their souvenir shirts, they brought the concept of casual, “hang 10” living back to the mainland. “And these are the young men who actually become key leaders in the Silicon Valley revolution,” she explains. Aloha Fridays then, weren’t just the precursor to Casual Fridays, but might just have been the catalyst that caused the relaxing of dress codes and workplace etiquette around the world.

Up there with jeans, Dr Bradley says, the aloha shirt is one of the greatest American sartorial inventions. Why, then, has it been the subject of controversy and derision over the years? And why did Mr Luhrmann’s 1996 proposition grate on our stylish sensibilities until recently? “We go through periods of time where things are kitschy and then things are valuable,” she explains. “From the 1970s forward, it’s like the designers in Hawaii kind of lost their way.” And it seems that nowadays something gets lost in translation the further production gets from Hawaii. “[These designers] probably haven’t had the morning I had,” Mr Hope says. “This morning, I saw a 180-degree rainbow, drove through the coconut trees as we went to the beach, and swam with turtles and tropical fish in a beautiful warm ocean.” But, according to Dr Bradley, the tide might just be turning. “The good designs that are coming out today are reminiscent of the stuff from the golden years. It was really good art, that just happened to be done on textiles.”

The men featured in this story are not associated with and do not endorse MR PORTER or the products shown