THE JOURNAL

Original Nike Dunk High, 1985. Photograph courtesy of Nike

“People can be super, super sensitive about this, so I just want to make sure that they know that you and I know the difference,” is how Ms Elizabeth Semmelhack, revered sneaker author and senior curator at Toronto’s Bata Shoe Museum, reacted when we revealed our plans to tackle the history of both the Nike Dunk and Nike SB Dunk in one story. (*Yes, it’s complicated.) And we didn’t even get around to mentioning our plan to include the arcane Nike Dunk Pro B and Nike Dunk CO.JP models while we were at it.

Rest assured athletes, skaters and mercurial sneakerheads, here at MR PORTER, we know our Stüssy Cherries from our Viotechs; our Skunks from our Michigans; our Smurfs from our Freddy Kruegers. To our other readers: keep calm. You too will soon be fluent in the native tongue of the Dunkverse. To begin our decoding of the Nike Dunk line’s tortuous history, we must first journey back to the mid-1980s – the epoch of Joyce Byers, Ms Whitney Houston and, most notably, Mr Michael Jordan.

Fresh from creating the groundbreaking Air Jordan 1, sneaker designer Mr Peter Moore was probably in need of a long holiday – but instead, he was tasked with sketching another sneaker, codenamed at the time, the “College Color High”. As its working title implies, the kicks were part of a fresh initiative to target varsity basketball players.

The sneaker had to be desired by young athletes, who were paramount to Nike’s successes at the time, and constructed with elements to enhance their performance – viz, resilient cushioning and lateral support. But the true genius of the idea was that it got the up-and-coming generation hooked, encouraging future stars to develop a relationship with the brand early on in their career.

“At this time, the revolution in basketball shoe construction was well underway,” says Mr Kevin Imamura, global footwear R&D for Nike SB , the skateboarding division of the sportswear superbrand. “The Dunk was able to reap the benefits of several earlier Nike shoes like the Air Force 1, the Terminator the Air Jordan 1.”

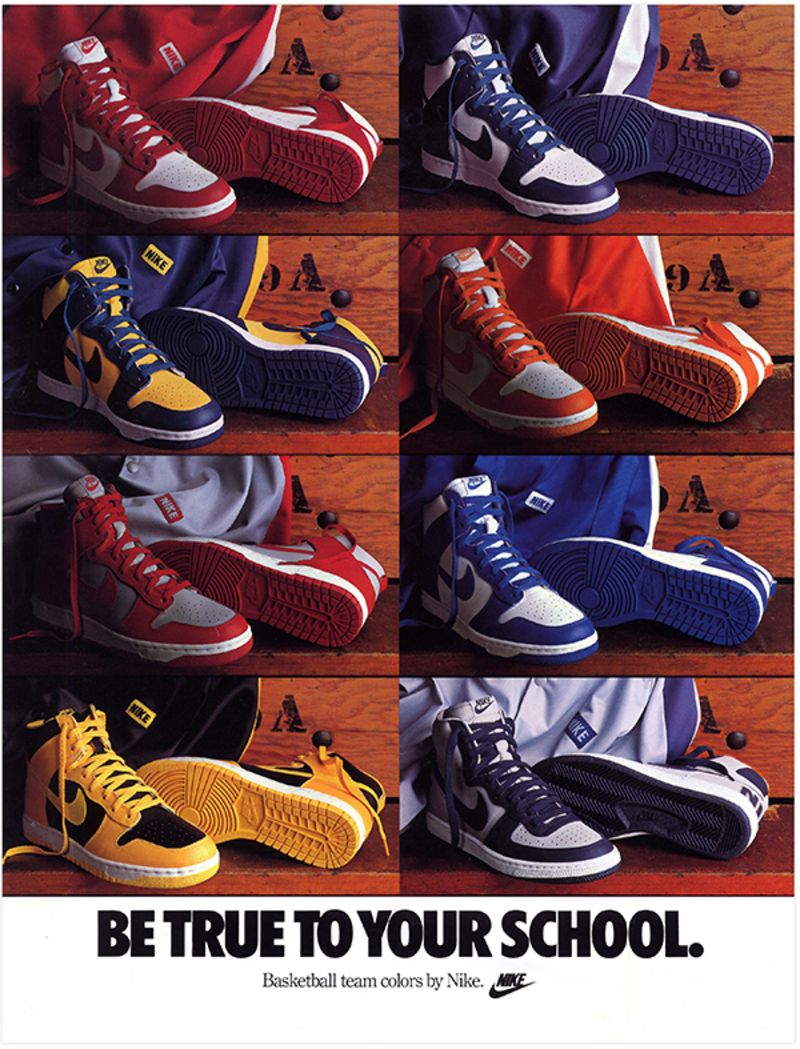

And so, in August 1985, the Nike Dunk High was born: a sneaker that offered athletes and fans a way to sport their college team’s colours with flair. Aptly, the first campaign was titled “Be True To Your School”. “It was the sneaker of college basketball and was offered in a wide range of colourways, which made it more of a chameleon,” says Ms Semmelhack. “It was adaptable.”

Original “Be True To Your School” print ad, 1985. Photograph courtesy of Nike

For a moment in time, the sneakers were ubiquitous. The high-tops had tangible appeal beyond the confines of college arenas, especially within black communities and urban subcultures. Younger generations loved the punchy colourways, which complemented their personal style. They also had the chance to catch sight of the sneakers in films such as Mr Spike Lee’s _School Daze _(1988), cementing their street credentials. But, alas, none of this was enough to stop the newly formed Jordan line overshadowing its more accessible counterparts.

By the early 1990s, Dunks were being flogged at discount stores, handed down to siblings and neglected in dusty attics. They were old news. Until, that is, the New York skate scene adopted them.

Skaters appropriated Dunks because of their durable construction and cup-sole shape. “It offered stability while still allowing for skaters to feel the deck of the skateboard,” says Ms Semmelhack. Plus, they were cheap, obtainable and easily styled with the B-boy look skaters were opting for at the time (think DC Shoes x Wu-Tang Clan vibes). “It [was] everything a skater could want,” says Mr Imamura. “Grip, comfort, protection, durability and last but not least, it looked incredible. It literally spoke to skaters.”

Which begs the question: why did skaters only gravitate to Dunks once they’d fallen out of favour? It’s simple. The Dunk High was originally a basketball sneaker subject to hype. Skaters, on the whole, preferred to go against the grain.

At the time, Nike failed to comprehend the Dunk’s affiliation with skate culture. Hence, its attempts at tapping into the insatiable skateboarding scene with flashy, overwrought silhouettes – including one named Choad (chuckle if you must) – during the mid-1990s, which flopped. Towards the end of the decade, Nike had an epiphany – the brand realised the answer to cracking the skateboarding market had been in plain sight for years.

Nike Dunk Low CO.JP, 2017. Photograph courtesy of Nike

Thus, in 1998, the Swoosh updated the Dunk High and rereleased it in familiar colourways. The nuances, including a nylon tongue, strategically favoured the skating experience. As a result, youngsters and seasoned skaters alike could all be found donning Dunks at their local skatepark.

Just one year later, a low-top take on the Dunk emerged on the West Coast and across the Pacific in Japan. Named the Dunk Low Pro B and the Dunk Low CO.JP respectively, these experimental Dunks – featuring a slew of different colours, patterns, textures and design features – were the result of regional divisions going rogue.

“Prior to Nike SB, the Dunk Low Pro B was in existence,” says Mr Imamura. “It was the first Dunk to incorporate the ‘fat’ tongue with extra padding and elastic straps, which had performance, fit and aesthetic benefits.” The two silhouettes spread across the world, satisfying skaters until Mr Alyasha Owerka-Moore – lifelong skater, streetwear designer and founder of Alphanumeric – refined the shoe in 2001.

Mr Owerka-Moore collaborated with Nike to release the Alphanumeric Lightning, which, according to Mr Imamura, was constructed with a “thicker tongue which offered better comfort, a plusher fit and protection from the board if it struck the top of your foot during trick attempts”. The inclusion of an ultra-comfy insole also made a big impact.

The Lightning was scheduled to release exclusively to friends and family of the Alphanumeric brand. That’s until Mr Sandy Bodecker, Nike’s vice president of special projects, discovered (and then, fell for) the customised model. To his mind, the shoe heralded the beginning of a new Nike era.

Mr Bodecker’s ambitious mission to bridge the gap between Nike and skateboarding began with a blue and grey sample indistinguishable from Mr Owerka-Moore’s take on the Dunk Low. He dubbed his beacon of hope the Nike Dunk Low Pro SB.

The sample was created to help Mr Bodecker showcase the concept of an SB Dunk to skate shop owners, a model he was looking to stock exclusively in their stores. He was eager to gauge their opinions, especially those who were anti-Nike. It was a listening exercise – a demonstration to prove the skating community was being heard.

“In the late 1990s and early 2000s, influential brands of the time helped create the ‘Pro B’ version of the Nike Dunk with extra padding,” says Mr Yu-Ming Wu, founder of Sneaker News. “So, it made sense when Nike set up the skate division that the Dunk was the model of choice.”

And it worked. The skating community got on board. Mr Bodecker founded the Nike SB diffusion line and The Nike Dunk Low Pro SB went into production.

“When Nike SB launched in the spring of 2002, the Dunk Low Pro SB incorporated the fat tongue and elastic straps [of the Dunk Low Pro B],” says Mr Imamura. “But it also included a brand-new drop-in sockliner that had a Zoom Air unit in the heel and a Poron foam bed in the forefoot for extra cushioning. Later that year, Nike SB offered a Dunk High that also had a fat tongue and the same sockliner.”

Nike Dunk Low Pro SB, Mulder, 2002. Photograph courtesy of Nike

The Dunk Low Pro SB originally dropped in four colourways inspired by Nike’s skate ambassadors Messrs Richard Mulder, Reese Forbes, Gino Iannucci and Danny Supa. From inception, the shoe proved immensely popular.

Both skaters and sneakerheads were willing to queue for hours (which, later, turned into days) to get their hands on a pair. Especially once Nike began collaborating with the likes of Futura and Supreme. As a result, the sneaker resale market started to boom – especially on consumer-to-consumer websites such as eBay.

“The alterations were small, but the fact that they launched the new model only in skate shops and quickly began to do collabs signalled a new era,” says Ms Semmelhack. “Many of these sneakers have gone on to become holy grails, such as the 2005 Pigeon designed by Jeff Staple.”

The 2000s were the golden age of Dunks. The Nike Dunk Low Pro SB was adorned with everything from high-fructose hues to lager logos to Parisian paintings. A SB Dunk High and a Dunk Mid Pro dropped, the latter constructed with a made-for-flip-kicks stitch and turn overlay, later incorporated into other Dunks. Mr Paul Rodriguez won gold at the X Games wearing Low Pro SB Cinco De Mayos. And anyone who was anyone was sporting a pair – including hip-hop legends Messrs Pharrell Williams and Andre 3000. But, as we all know, all good things come to an end.

Fast-forward to the mid-2010s and a different story was playing out. The then scarce Dunk sneakers – overhauled in 2011 with less rubber, a Phylon foam pad and an improved tread pattern – were more likely picked up at suburban Nike outlet than an inner-city resale store. This was a result of oversaturation. “A lot of the general releases ended up on sale at the big-box retailers, and most sneaker fans started to look at other models,” explains Mr Wu.

Sure, Ms Rei Kawakubo’s transparent take on a Dunk High for Comme des Garçons Homme Plus (2016) was heartily endorsed by the beau monde, and the low-top edition of the SB Dunk High De La Soul (2015) grabbed the attention of hardcore sneakerheads, but no one was willing to jump through hoops to cop a pair – not even skaters. Dunks were pronounced dead. And dead they stayed, until Mr Travis Scott resurrected them.

As Houston-born rapper Mr Travis Scott ascended to stardom circa 2018, he did so channelling his hip-hop predecessors in Nike Dunk grails. As a matter of course, die-hard fans were eager to cop Mr Scott’s style – including his collection of deadstock sneakers. And once he inspired Ms Kylie Jenner (the mother of his child) to start flexing in Dunks for the ’Gram, her millions of followers also started scouring the web for a pair.

Diamond Supply Co. x Nike SB Dunk Low Diamond Dunk, Tour Yellow, 2005. Photograph courtesy of Nike

Shortly after Mr Scott became indivisible with Dunks, a historic sneaker moment occurred: ComplexCon 2018’s Diamond Dunks-gate.

At the LA-based event, just 250 pairs of the Diamond Supply Co. x Nike SB Dunk Low “Canary Diamond” creps were scheduled to drop. Rumours of the extremely limited release sent ticket holders wild and eventually led to a riot. Later, and although no pairs were officially sold at the event, attendees were spotted escorting pairs off of the premises, eventually listing them online for up to $5,000.

It’s understandable if the teams at Nike and Nike SB, watching this event play out, were gleeful. The demand was there; all the Swoosh had to do was create hype. Naturally, they enlisted the help of Mr Scott and man-of-the-moment Mr Virgil Abloh.

In 2019, Messrs Scott and Abloh lent their signature styles to Dunk models, the former releasing the SB Dunk Low Cactus Jack – a coveted sneaker decked out in bandana prints – and the latter dropping an industrial Off-White take on a Nike Dunk Low. By winter, a resurgence was afoot, laying the groundwork for 2020: the year of cow-print patterned, green-furred, Hennessy-themed Dunks.

“Thirty-five years later, the Dunk is more popular than ever – highly sought-after by sneaker collectors, casual fans and the fashion crowd,” says Mr Wu. “It’s one of the most iconic models ever created.”