THE JOURNAL

At this point, Mr Nyjah Huston, who is reportedly the world’s highest-paid professional skateboarder, has attained virtually everything an extraordinary decade-long run in his sport can get you – 12 X Games gold medals, a likely spot on the US’s first ever Olympic skateboarding team, endorsement deals with Monster Energy and Nike, and a garage full of high-end vehicles. He’s appeared on HBO’s Ballers as a version of himself who is too busy car shopping to return The Rock’s calls. He wakes most mornings in a modern Laguna Beach five-bedroom house – you can see Catalina from the cloud-white sofa in the living room on a clear day – and trains at his own private skate park, built to his specifications inside a 10,000sq ft warehouse in nearby San Clemente.

Mr Huston also has his own signature shoe, the Nike SB Nyjah Free, and at least one fan devout enough to pull said shoe off his own foot and gulp a beer out of it in Mr Huston’s presence, at Mr Huston’s urging, for Mr Huston’s 3.9 million Instagram followers to see. This happened last year at a club in Toronto.

“One of the homies came up and he had my shoes on, and I asked him to do it and he was down,” says Mr Huston. “They were all old and gross and shit, but he was still down.” When asked if the guy at least got new shoes out of the deal, Mr Huston laughs and admits he’d had a bit to drink and neglected to take down his admirer’s information. “I wish I knew his name,” he says. “I would send him a new pair ’cause that was sick.”

At the moment, Mr Huston, 25, exists in a weird zone, fame-wise. He’s revered enough among his fellow skateboarders to compel one of them to drink from a shoe and when security guards chase him away from a skate spot on private property, they sometimes ask him to pose for a photo before he leaves – “I think that’s the best thing ever” – but he can still move through life like a normal person, more or less.

“People who don’t know who I am will ask what I do,” he says. “If I’m like, ‘Oh, I skateboard,’ they’re like, ‘Oh, you can make a living off of that? You make money off that?’ I’m like, ‘Yeah. I do all right for myself.’”

He feels for famous people who’ve lost that freedom, he says. “I know Bieber a little bit,” he says. “It would suck to not be able to go out there and be a normal person.”

“Bieber”, of course, is Mr Justin Bieber, who paid a visit to Mr Huston’s park in San Clemente last autumn, while his wife, Ms Hailey Baldwin, was at her bachelorette party with guests such as Ms Kendall Jenner. According to Mr Huston, Mr Bieber can indeed skate (“He can actually land tricks”) and was “very appreciative of me and my friends treating him like a normal person. Not like how I’m sure a ton of people treat him on the daily. Like, always wanting something from him. He was just stoked to have a sesh with the bros. And I thought that was tight.”

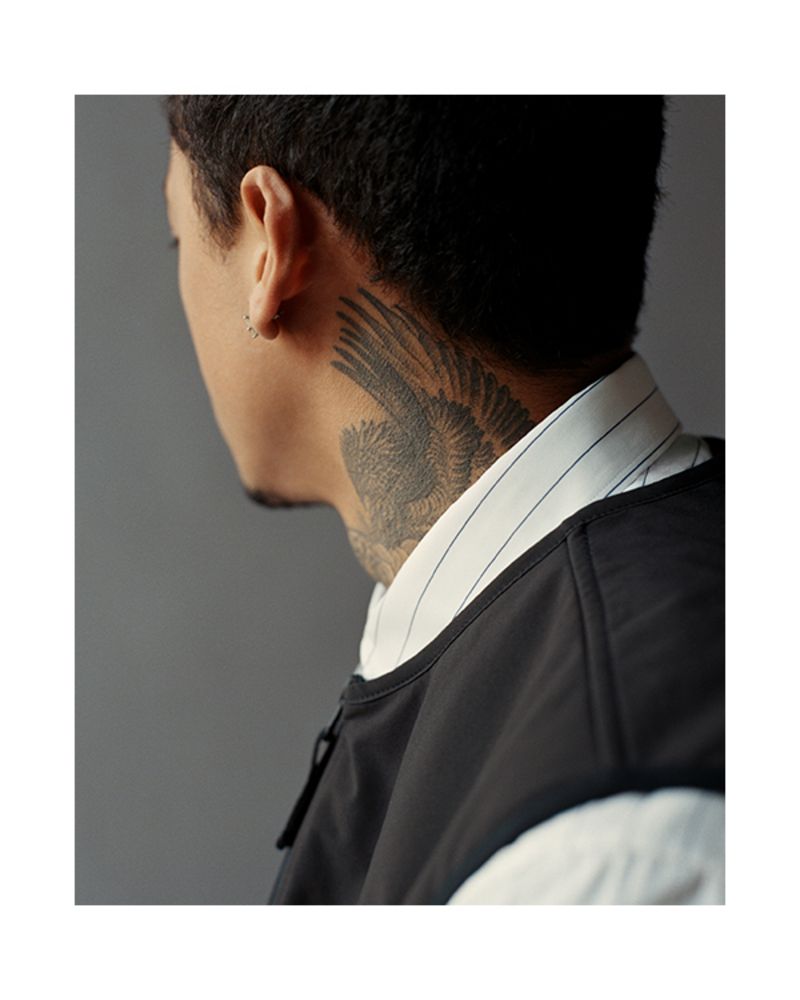

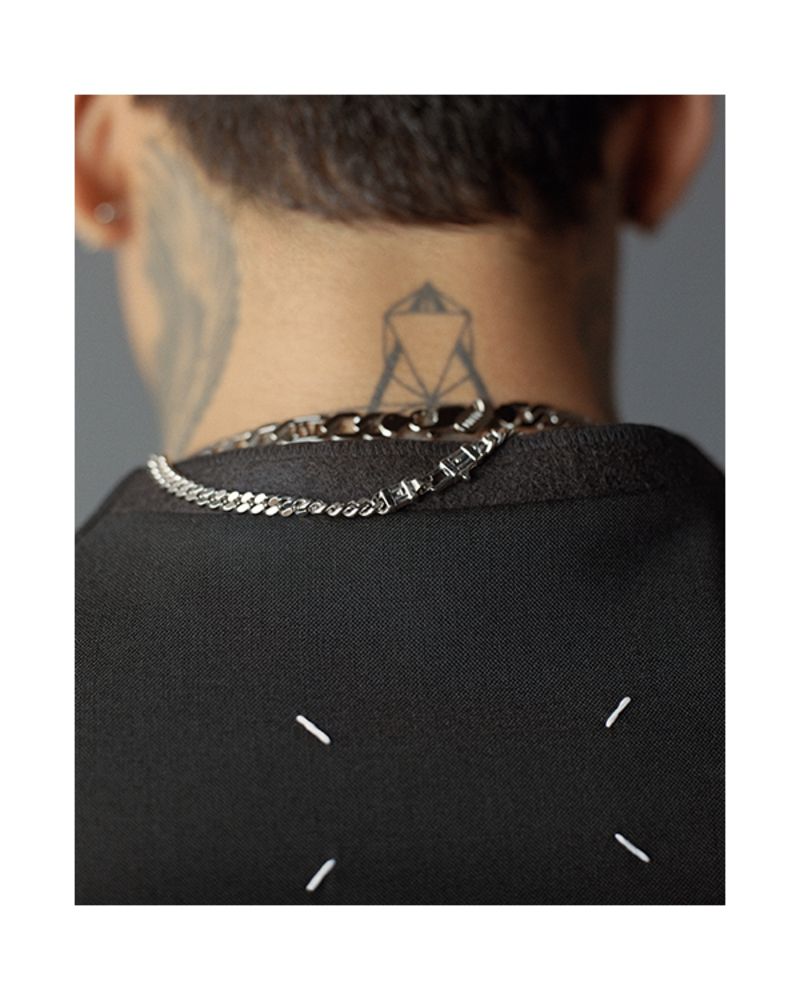

Mr Huston stands just over 6ft if you measure from the top of his Eraserhead box fade and is tattooed more or less from the neck down – wolves and mandalas, “SKATE AND DESTROY” in the crook of one arm, balanced on the other arm by “LIVE AND ENJOY”. Restless in person, Mr Huston does not so much stop as pause, but for the moment he’s here in the afternoon sun outside a Hollywood sound stage, decompressing after a photo shoot, back in the functional gym clothes he prefers most days, talking about the Tokyo Olympics. This year’s games will include skateboarding for the first time. Mr Huston is one of 21 skaters chosen for USA Skateboarding’s first ever Olympic team and will be in Japan at the end of July. The events of this summer will likely cement his status as the sport’s most visible mainstream ambassador since Mr Tony Hawk and will be an opportunity to bring home one of the few street skating prizes he doesn’t already have.

He is, as you might imagine, honoured and stoked to skate for his country, and intends to win, but he’s also trying as hard as he can to approach Tokyo like it’s just another contest.

“I try not to put too much extra pressure on myself,” he says. “I’ve always been hard on myself when I don’t perform how I want to. And skateboarding, it’s not like it’s a race. It’s not like whoever is the fastest and trains the hardest wins, you know? It’s literally the complete opposite. It’s so technical and the smallest little thing can go wrong. A little bit of nerves and you can fall. I’m gonna do my best, like I always do, but I can’t sit here and tell you I’m going to win. It’s just not how skateboarding is.”

It’s a perfectly self-effacing pro-athlete answer. Mr Huston has been called the Mr LeBron James of skateboarding, a designation he seemed to wink at in his 2019 skate video ’Til Death by skating a dizzyingly long metal railing, his speciality, in a number 23 Cavaliers jersey while Huncho Jack’s “Saint Laurent Mask” bumps on the soundtrack. ’Til Death, 11 kinetically edited minutes of Mr Huston putting various California handrails to uses undreamt of by the Americans with Disabilities Act, might be the best introduction to Mr Huston and his skating style, which is daring, but also almost unnervingly clean and precise. These days, Mr Huston says, he thinks as much about aesthetics – “looking more fluid and flawless on the board” – as he does about pulling off bigger, crazier tricks.

“People are always like, ‘Oh, he’s so consistent. He never falls,’” says Mr Huston. “But then there’s the whole other street skating side of it, where I’m known as one of the dudes that eats the most shit, you know? And takes the hardest falls and has gotten back up and still went for it.”

As anyone knows if they’ve ever tried to learn, falling down is a huge part of skateboarding. The inclusion of often brutal “slam” footage remained an aesthetic constant in promotional skate videos even as the form has migrated from VHS to YouTube. But when we see Mr Huston fall, it’s more than a demonstration of physical toughness and dedication. In a video such as ’Til Death, the occasional shots of Mr Huston blowing a trick serve to humanise and render relatable an athlete who might otherwise seem too elite to be a usefully aspirational figure, a T-1000 in skinny jeans and a hoodie. So a clip of Mr Huston losing his balance and his board and clocking his head on the pavement beneath a 16-stair rail at Hollywood High School gets milked for maximum drama. The screen goes black, a pathos-rich Mr Meek Mill song plays, a long shot of Mr Huston’s motionless body gives way to a close-up of blood on the concrete, spattered and pooling.

“People actually thought that we poured fake blood down,” says Mr Huston. In fact, he had a head wound that required three staples – he says this like three staples is a no-big-deal amount of head staples for a person to need – but understands why the haters cried corn syrup_. _“I would not have thought that much blood came out of me,” he says. “But it was real, man.”

Mr Huston grew up in Davis, California. His father, Mr Adeyemi Huston, was a Rastafarian who raised his family according to those principles. He put Mr Huston on a skateboard when he was four or five years old. “He would push me to skate big rails” – outdoor banisters, among the most omnipresent and harrowing obstacles in street skating, given their proximity to flights of unyielding concrete stairs – “and do gnarly shit when I was a kid,” says Mr Huston. “I think that’s one of the reasons why nowadays that’s my favourite shit to skate, even if I’m not going for the biggest shit to win a contest. If I’m out skating with my boys and I see a big rail, I want to hit it.”

Mr Huston says that while he’s grateful for his father’s early encouragement, it turned into pressure as he got older. “I feel like he was trying to live through me,” he says. “His children, me and my brothers, too. Having that skateboarding lifestyle and making something out of it. Because he used to be a skater, back in his teenage years.

“No matter how hard I got pushed to do it, I wanted to be doing it. But that’s why it was annoying and confusing. Because, like, why push someone so hard to do something when they want to be doing it anyway? And they clearly have that love and passion for it? There were definitely some rough times. And it was hard to understand sometimes. It’s still hard to understand, to this day.”

In footage from his pre-teen years, Mr Huston is a tiny dynamo with dreads down his back, already staggeringly good at virtually everything. So good there were rumours that he was a teenager who’d lied about his age. He was profiled by the seminal skate magazine Thrasher at age nine, finished first at the star-making Tampa Am skateboard contest at 10 and skated in the X Games for the first time one year later. He was, at the time, the youngest competitor in X Games history. “If he can make it through his teen years,” World Cup Skateboarding president Mr Don Bostick told The New York Times in 2006, “I think he’s the future of street and park skateboarding.”

As it turned out, Mr Huston’s teen years were not without incident. The same year Mr Huston made his X Games debut, his father relocated him and the rest of the family to a 26-acre farm in rural Puerto Rico.

“It was my dad trying to stay away from the normal world,” says Mr Huston, “and keep us secluded from those normal things, going to normal school, getting into drinking and girls and stuff.”

“We purposely separated ourselves from society,” Mr Huston’s mother, Ms Kelle Huston, told the skateboarding website jenkemmag.com in 2014, “and basically lived as a mini cult.” As a result, Mr Huston’s burgeoning pro career began to derail.

Eventually, his mother left the marriage and moved back to California with Mr Huston’s brothers and sister while he and his father were away at a contest. In 2010 she was awarded custody of Mr Huston, who moved back to California. He hasn’t spoken to his father in five or six years.

“I heard he might be in Vegas or something,” he says. “Who knows, man? That’s how life goes sometimes.”

When Mr Huston and his mother showed up at the first Street League Skateboarding contest in Glendale, California, that first year back stateside, they were broke. Street League founder Mr Rob Dyrdek lent them money for a hotel room. Mr Huston went on to win $150,000 at that contest, resumed his pro career in earnest and embraced life outside the “mini cult”. He’d never tasted ice cream, eaten meat, cut his hair, been tattooed, or been drunk, and in short order he did all these things.

“It was some of the best, best times in my life, that couple of years,” he says. “Really fun, simple times. Just going out there every day, every night, lighting up spots, hanging with the boys and getting footage. Just having fun being a kid. It was sick.”

Though he’s prepping for the Olympics, he no longer skates every day. His 25-year-old body won’t let him. The odd skull staple is one thing, but what gets you, he says, is “stuff that lingers. Rolled ankles. I’ve had a knee injury for the past eight years now, just a constant bone bruise. Lately, I’ve been dealing with this shoulder injury.”

The clock is real for any athlete. If skateboarding had become an Olympic sport in 2024, rather than 2020, there’s a real possibility Mr Huston would have missed his chance at gold. [Ed’s Note: As we publish, the International Olympic Committee says it intends to move forward with the games despite increased pressure from the community to cancel or postpone.]

“I feel like I’ve at least got another five years in me,” he says. “It’s something I’ve been thinking about more and more as I get older. Not how long can I skate for because, no matter what, I’m gonna be skating. I might not be doing the craziest shit, but I’m gonna be out there having fun, still skating when I’m 40, maybe even 50 years old. You still see Tony Hawk out there. He’s 50 and still shredding, and that’s a big inspiration for me, but as far as really being out there and competing, you see most dudes go till around 30.”

He mentions Messrs Paul Rodriguez, 35, and Chris Cole, 38, both still active pros. “But they didn’t start as young as I did, and they weren’t jumping down 16 stairs when they were nine years old, y’know? I definitely got a big head start, but my body’s been through a lot. I think if I can still be out there competing until I’m 30, I’d be stoked on that.”

Grooming by Ms Randi Petersen