THE JOURNAL

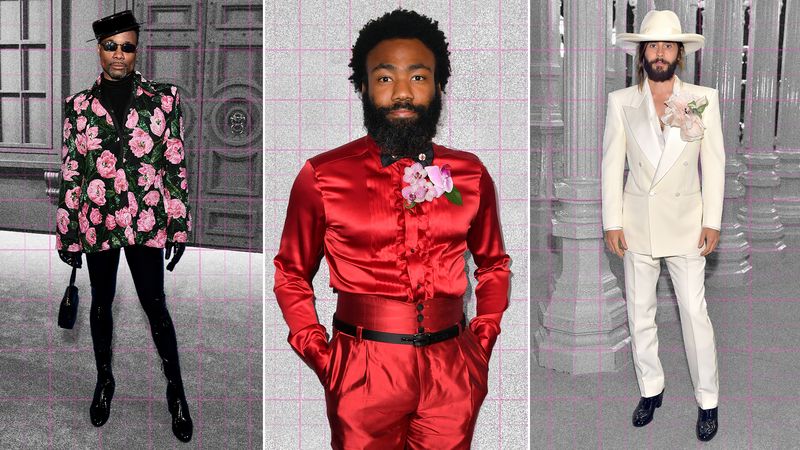

From left: Mr Billy Porter, London, 15 February 2020. Photograph by Mr Jeff Spicer/Getty Images for BFC. Mr Donald Glover, Beverly Hills, 25 October 2019. Photograph by Mr Frazer Harrison/Getty Images for BAFTA LA. Mr Jared Leto, Los Angeles, 3 November 2018. Photograph by Ms Stefanie Keenan/Getty Images for LACMA

When it comes to men’s style, Mr Harry Styles is an outlier. To date the only solo man to shore up on the cover of US Vogue in the magazine’s 128-year history, his performance at this year’s Grammy Awards had a similarly epoch-making vibe. Opening the ceremony with his hit single “Watermelon Sugar”, the singer wore three outfits, each one a big look, supercharged by his ongoing association with Gucci. But of all the clothing on display, one piece stood out: his feather boa.

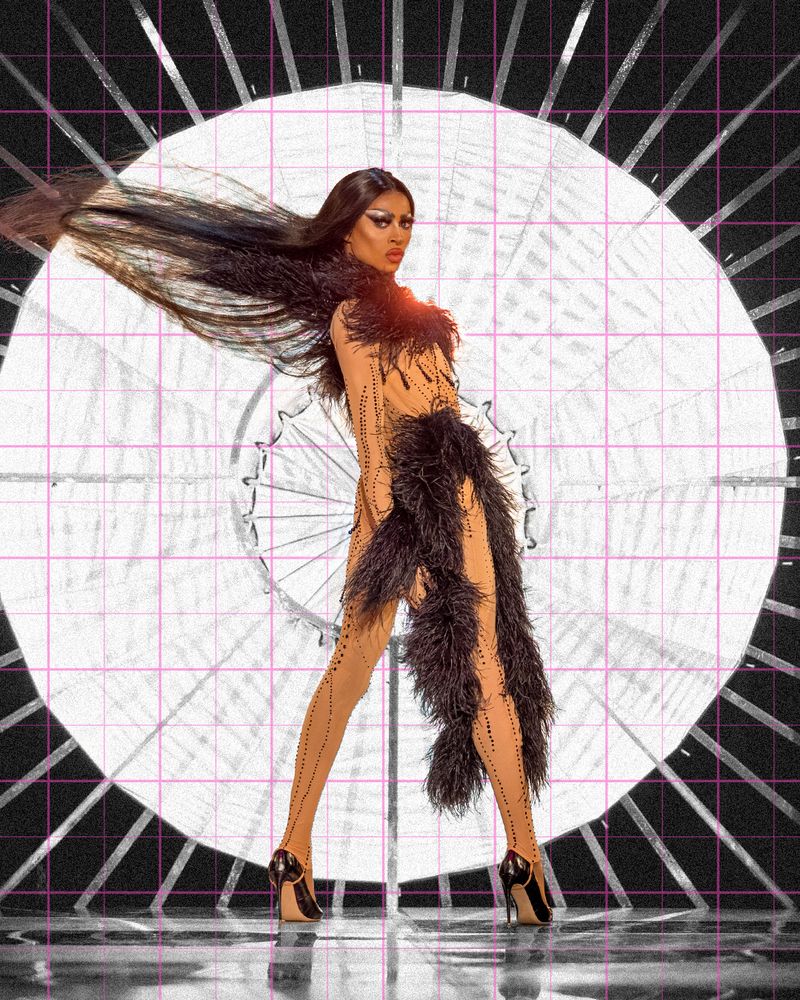

From the craze of the late 1800s – a time when feathers were ubiquitous in fashion, with devastating consequences for numerous species of bird – the feather boa resurfaced again in the Gilded Age of the 1920s and, perhaps more regrettably, again in the 1990s (a question mark hanging over the supposed sartorial nous of Sex And The City). Invariably seen as a women’s accessory, or as a piece of campy costume, the men of the modern era who have made it part of their wardrobe – think Messrs Marc Bolan and David Bowie – often did so to evoke a very theatrical form of femininity, one less and less connected to women themselves. And here it was again, wrapped around Styles. Only, truth be told, Tayce got there first.

“I’ve got pictures of me from a baby to 10 years old in wigs, dresses, anything I could find in my mum’s room,” Tayce, a finalist on RuPaul’s Drag Race UK season two, recently told The Guardian of growing up in Newport, South Wales. “My parents would take me to McDonald’s once a week, as a treat, and I would wear this wig and feather boa. I was nine!”

To phrase it in a way that would hopefully illicit a cackle from Ms Michelle Visage, Mr RuPaul Charles’ fellow onscreen judge, the Drag Race franchise has long since penetrated mainstream culture. Its vernacular – “throwing shade”, “the realness”, “she owns everything” – is in common usage today, to the point that many users aren’t even aware of the etymology. (RuPaul, in turn, drew much of it from the underground drag scene that raised him, best captured in the cult 1990 documentary Paris Is Burning.)

The soft-power reach (that innuendo again) of the series has undoubtedly brought LGBTQIA+ causes and concerns to the fore. In recent seasons, the show has itself done some soul-searching, dropping gendered pronouns and introducing trans contestants (Gottmik, in the current US series, is the first openly trans man going into the competition) – and even a heterosexual man. For every manufactured culture war to spiral out of Twitter and into our daily news cycles, the success of Drag Race is a reminder that progress is still quietly being made.

But it is not just our relationship with gender and sexuality that is evolving. Our exposure to this previously sidelined subculture has come at a time when what is considered suitable attire for a man is also changing. And if a decade ago, Mad Men left its mark on what we wore, it is not a stretch to suggest that the impact of Drag Race is now also being felt in our wardrobes.

Tayce on RuPaul’s Drag Race (2021). Photograph by Mr Guy Levy/World Of Wonder/BBC

From more prominent jewellery (pearls!) and skirts to hair and nail colours, most of the trends currently sweeping through menswear tap into this blurring of gender norms. With its camp theme, and Drag Race contestants among the attendees, the 2019 Met Gala was a turning point. But many of the men we consider style icons today have been using other high-profile social events as an excuse to express their own sartorial creativity.

The likes of Mr Billy Porter, Lil Nas X or Mx Ezra Miller and the elaborate, perhaps avant-garde outfits they’ve worn to award ceremonies are the most obvious examples of this more fluid approach to clothing. But equally figures far from limited to Messrs Donald Glover, Lakeith Stanfield, Jared Leto, Timothée Chalamet and A$AP Rocky continually push boundaries with what they wear in much the same spirit. The aim isn’t to incorporate womenswear per se, more to embrace experimentation and step away from the conservative nature of classic menswear. And while it’s unlikely that the runway looks of previous Drag Race winners Jaida Essence Hall, Yvie Oddly or Aquaria directly informed the ensembles adopted by the aforementioned men as they worked the red carpet, it is also naïve to assume that they got dressed in a vacuum.

“You could dismiss it as grown-ups still messing about in the dressing-up box, but we all make similar decisions about who we want to be when we pick out what to wear every morning”

It helps that one of the key themes running through Drag Race is universal: struggle. This is what has underpinned the series, and its spin-offs, since its inception in 2009. Not just in terms of the competition format, lifted wholesale from America’s Next Top Model, but also the contestants’ backstories, often teased out of them while applying makeup in the Werk Room, where the queens prepare for their next challenge. You don’t get to this level of this particular field – and make no mistake, Drag Race really showcases the very best of an entire creative industry – without facing some degree of hardship along the way.

True, the sob stories that litter America’s Next Top Model, The X Factor and America’s Got Talent, even The Great Pottery Throw Down, have become a central pillar of the reality show. But few of the competitors in each of these programmes encounter the sort of bullying, abuse and often violence that is typically laid bare as par for the course of Drag Race. In other shows, it has become a trope; in here, it’s a fact of life. But does it have to be?

As part of each Drag Race series’ finale, contestants are presented with a childhood photograph. They are then asked to give advice to their younger selves. For most, this is a cathartic experience. In this year’s UK final, counsel included “You will struggle a lot with your dad,” and “Don’t hide yourself from everyone… not everyone is out to get you.” When it came to Tayce, her (she was in character) guidance to her six-year-old self, pictured sporting a neighbour’s wig, was more of a straightforward makeup tutorial. “Love the outfit, girl. You look fabulous,” she beamed. “You’re going to show McDonald’s a real good time.”

Tayce’s origin story is perhaps unusual; that his dad was formerly a guitarist for Wham!, an insight casually tossed out there in the same episode, may account for his family’s acceptance of who he was. But if Drag Race has done anything, it has ensured that future contestants will be more likely to feel similarly supported as they grow up.

To the wider audience it has amassed, what the show illustrates is the hold that clothing has over our perception of identity. The person you see in the Werk Room or in the confessionals is not the end product that you see on the runway. Contestants are judged on their eye for a good outfit, but also their intimate knowledge of clothing – the ability to sew is encouraged (or rather the inability to sew is met with serious shade). And while you could watch Drag Race and dismiss it as a bunch of grown-ups still messing about in the dressing-up box, we all make similar decisions about who we want to be when we pick out what to wear every morning. As the world begins to wake up from its Covid hibernation, perhaps even more so.

As ever, RuPaul put it best: “We’re all born naked and the rest is drag.” So, whatever your plans for today, make sure that you look fabulous while doing it. Even if the only place you end up is McDonald’s.