THE JOURNAL

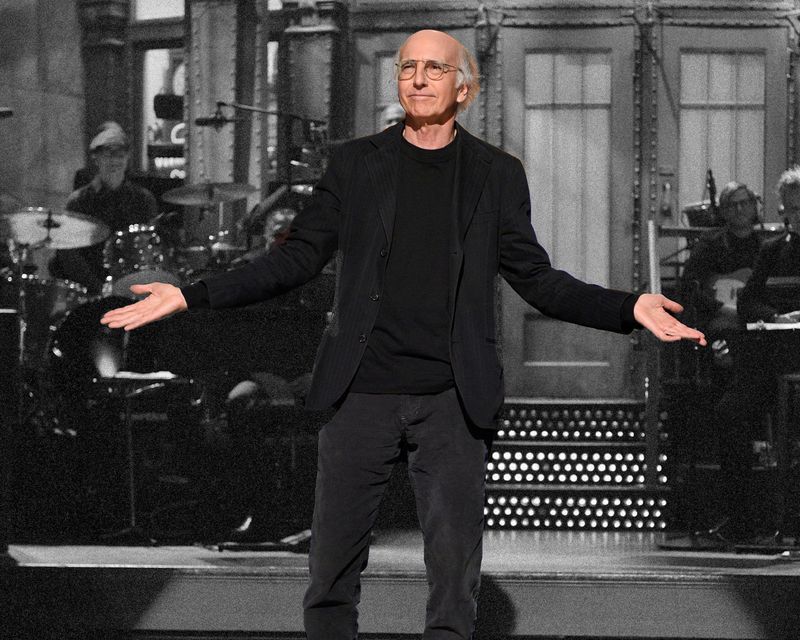

Mr Larry David during his SNL monologue, New York, 6 February 2016. Photograph by Ms Dana Edelson/NBCU Photo Bank/NBCUniversal via Getty Images

Cast your mind back if you will, or can, to the year 2000. Not long before, political scientist Dr Francis Fukuyama had declared history to be over, reformist president Mr Vladimir Putin had just swept to power in Russia and the closest thing we had to an existential threat was a computer coding glitch that ended up outing 150 slot machines in Delaware – and that’s about it. From today’s perspective, it sounds more like a holiday than a thought experiment.

If reality looked very different two decades ago, reality TV – well, that was barely out of nappies. The first series of Big Brother had only launched the year before, in the Netherlands, and wouldn’t shore up in the UK or the US until that summer. “Scripted reality”, therefore, wasn’t on anyone’s radar, which probably made the pilot for Curb Your Enthusiasm a hard one to pitch.

In truth, Mr Larry David had blurred the lines between fact and fiction with his previous series, the hit 1990s sitcom Seinfeld, which he’d co-created with its star, Mr Jerry Seinfeld. With Mr Seinfeld as his foil – and actor Mr Jason Alexander playing on-screen Jerry’s sidekick, George Costanza, an avatar for Mr David – Mr David helmed the writers’ room, where he mined his team’s minds for embarrassing and trivial anecdotes.

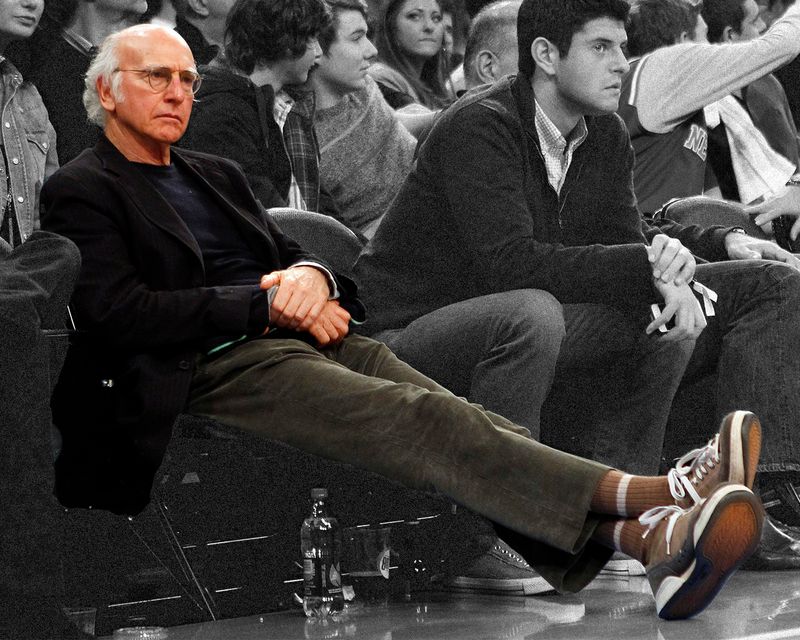

Mr Larry David watching the New York Knicks play the Cleveland Cavaliers, Madison Square Garden, New York, 15 December 2012. Photograph by Mr Adam Hunger/Reuters

One early season of Seinfeld skirted especially close to Curb, with a narrative arch that followed Jerry and George’s attempts to get a sitcom based on their own lives, “a show about nothing”, off the ground. This turned out to be an overly meta cul-de-sac, but it obviously got Mr David thinking.

When Curb arrived in October 2000, two years after the last episode of Seinfeld, it was something that took a while to get your head around. Filmed in a lo-fi “shaky cam” style, the show centred around its writer, a grouchy, entitled, balding fiftysomething playing an exaggerated version of himself going through a perpetual midlife crisis. Maybe? And then there was the way he dressed. It was one thing for the wardrobe to reflect what the average schmuck wore, but had Mr David even bothered to comb what was left of his hair?

Of course, at the time, if like the clothes the show felt a bit phoned-in, we weren’t quite seeing the bigger picture. Just as Seinfeld and then Curb had tapped into our everyday grievances and spun them into comedy gold, Mr David had taken a very pedestrian dress code and turned it into an identity. And over the past two decades, and now into the 11th series of the show, he has rarely deviated from this look.

The circular spectacle frames and wild, white thatch – unbrushed in patches and, for the large part, absent. The crumpled blazer, probably navy, over a crewneck sweater, also navy or, at a push, grey. The comfort-fit chinos and cargo pants. The sneakers. Oh, the sneakers. Where Mr David’s erstwhile partner Mr Seinfeld was known for the chunky Nikes he wore, Mr David raised the stakes. It took the fashion industry, what, 15 years to catch up with the “dad shoe” trend. And while it pains us to reveal that the Larry silhouette by MR PORTER’s own line, Mr P., was not, in fact, named in honour of Mr David, he is as good as its spiritual wearer.

From Mr Steve Jobs to Mr David Lynch, numerous creative icons have, either by accident or design, latched onto the concept of a uniform. But Mr David went one better, turning it into a brand. Was the on-screen Mr David a caricature of himself or had Mr David, in real life, turned himself into a caricature? It didn’t really matter. “To pretend, I actually do the thing: I have therefore only pretended to pretend,” as French philosopher Mr Jacques Derrida once said. Or: “image is everything” (er, Mr Andre Agassi).

By drilling down into the minutiae of the everyday, Seinfeld earnt a name for itself coining foibles that we all could relate to – “regifting”, “double dipping” and “low-talking” come to mind. Puffy shirts aside, it did not, however, forge a fashion trend. So, while, thankfully, the “pants tent” never caught on, Mr David’s dress sense became notable precisely because of its anonymity. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the word “normcore” entered our lexicon in 2005, five years after Curb debuted. Coincidence or Davidian plot device? Either way, thanks to social media, we’re now all trapped in our own episode of the show.

Is this the real life, is this just fantasy? Perhaps they are one and the same.