THE JOURNAL

Mr Noel Gallagher walks into his recording studio and announces that he is hungover. He has good reason: life is opening up, the sun is shining outside and on the day before our meeting at his new space on the outskirts of London’s King’s Cross development, the singer, songwriter and restless force of nature had been at Wembley Stadium watching his beloved Manchester City win yet another trophy. Football is one of his three self-confessed passions in life, the others being music and his family. He could probably stretch to a fourth – socialising.

“We’re very sociable people,” he says of himself and wife, Ms Sara MacDonald. “I was at a party the other night and there were people saying they’d quite liked being at home for months and not having to think for themselves. I’m like, ‘That’s fucking mental.’ That’s the exact opposite of my family, we couldn’t wait to get out.’ It’s classic Noel Gallagher, a singular take on any given issue, embroidered with F-words and extracts from conversations he’s had, all served up with healthy dollops of attitude, conviction and comic timing.

Now 54 and a mellower version of the hard-living, fast-talking leader of what was the world’s biggest and most reliably argumentative rock band, Gallagher admits he is an optimist by nature. This much is evident from the numerous iconic songs he has written about having a good time, both for Oasis and as a solo artist (the 10th anniversary of Noel Gallagher’s High Flying Birds, his solo project, is now marked with a greatest-hits album). He maintains there were positives that came out of the lockdown experience, not least being able to mine a rich creative seam, which means he is now well ahead of schedule on his next solo album. But on a personal level, he admits his optimism was tested at times.

“Home schooling was tough on the kids. My kids don’t give a fuck at the best of times, far less when they are sitting in their own kitchen in their underpants, eating toast when they’re meant to be learning something.” Donovan, the eldest of his two children with MacDonald, is 13, and had just started at a new school when the second UK lockdown came into effect. Sonny, their other son, is nearly 11, while Anaïs, his daughter from his first marriage, is now 21.

“I had two young sons when I went away on tour in 2017 and when I came back in 2019 one of them’s got a ’tache and is calling me ‘bruv’, and the other one is wearing jewellery and saying, ‘Yo.’ I’m like, ‘Fucking hell, how long have I been away?’”

Being stuck at home was toughest on Donovan, he says. “He’s at that age where you don’t know who you are. You only get to find out who you are through your life experiences, but if you don’t have any, the internet decides who you are. You shouldn’t really let your kids gravitate towards the internet, but what do you do?”

Donovan, he says, has “entered the stinky teenage years” and “is aggressively underwhelmed by everything, including his little brother,” while Sonny is “the easiest, happy-go-luckiest lad you’re ever likely to meet”. On the whole, he adds, these two Gallagher brothers “get on great”.

Last September, Gallagher, MacDonald and their two boys moved out of London and settled in Hampshire. Having the extra space helped, he says, especially when cabin fever set in and it felt like everyone was, in his words, “seeing too much of each other”. Getting his studio up and running was another blessing, one that came at just the right time, offering him a creative haven and an escape from the countryside.

“You get over the midlife-crisis moment when you buy a fur coat and your trainers are more expensive than your mum’s house”

While there are certainly worse places for a rock star to hunker down than in his new, rural rock-star pile, Gallagher is a city boy through and through – and not just in terms of his football team. As such, he is an unlikely convert to mountain biking.

He describes standing in front of the mirror, having a conversation with his wife as he fastened a cycling helmet under his chin for the first time: “‘Do I have to wear a helmet?’ ‘If you get hit by a fucking tractor and you end up in a ditch, you’ll probably end up in a wheelchair.’ Possibly the worst woman in the world to be in a wheelchair with would be my wife,” he deadpans. “She’d drive me into a corner, facing the corner, and say, ‘I’ll be back in two days.’”

Gallagher and MacDonald met in Space, the legendary Ibiza nightclub, in the summer of 2000. He had recently stopped doing drugs and his first marriage had broken down. He got her number, which, he admits, he cherished like a “religious artefact”.

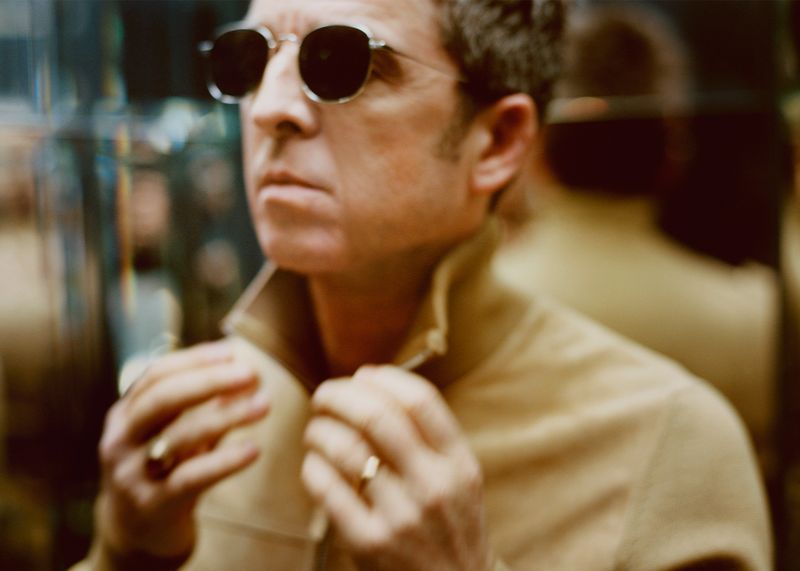

Today crisply dressed in plain white designer sneakers, slim-fitting chinos and a checked shirt over a white T-shirt, Gallagher is synonymous with a time and place, and yet his huge contribution to the culture over the past 30 years – a songbook that puts him in the most rarefied company; living the rock ’n’ roll life in the truest sense – makes him feel no less familiar in person. The voice, the eyebrows, the wit – which makes him reliably entertaining company – are important parts of the package, but so too is the hair, arranged, as always, in a style that’s exclusive to him.

He doesn’t bat an eyelid when asked what a cycling helmet and the lack of regular maintenance did to his hair during lockdown. “I’ve got Irish hair, so it grows out sideways,” he replies. “There were times when I looked like an IRA prisoner on hunger strike, which wasn’t ideal.”

He recounts an appointment with his doctor to talk about the vaccine and why he was having doubts about taking it. “[The doctor] said, ‘What’s the problem?’ I said hair loss. If I lose one strand of hair, I’m not fucking taking it. ‘Mr Gallagher,’ he said, ‘there is no evidence to suggest you will lose any of your hair.’”

But what if he did start to lose his hair? Would Noel Gallagher ever consider a hair transplant? “I don’t think so,” he says. “I mean, we are living in the age of the silly hat.”

After 18 years, seven studio albums and 22 consecutive top-10 UK hits, Noel Gallagher quit Oasis in 2009. “Bands are weird,” he says, which is one way of summarising an experience that resulted in sales of more than 75 million records. “You start off as young men and end up going all the way through to being middle-aged dads and all that goes with it.” Of course, he understands the clamour for a reunion but offers no indication it’s likely: “You don’t really understand unless you’ve really been in it. Once you’ve quit, there is no going back. There’s no point in going back.”

We don’t discuss the long-running feud with his brother Liam – it’s the one topic that’s off limits – although he does confirm that he and his estranged sibling have set up a film company together to release a documentary about Oasis’ historic live shows at Knebworth, which took place in front of 250,000 people over two heady nights 25 years ago. He has bittersweet memories of the event he describes as “the last great gathering of the analogue age”.

“In any era, ‘Don’t Look Back In Anger’ and ‘Live Forever’ are going to be pretty special tunes”

Gallagher is the ultimate analogue man. He claims he only got his first mobile phone in 2000 when he became a father and says his mistrust of laptops and iPads stems from a fear of pressing the wrong button and “a missile being launched from the Ukraine”. Social media, he insists, is “the most powerful, addictive, dangerous drug of all time”.

His disdain for screens and gadgets and online “medieval angry mobs” is very clear, not least when he describes looking out from the stage across the sea of faces at Knebworth and “not one single is person is doing that” – he mimes holding up a phone. “Mobile phones didn’t exist,” he says. “Thousands upon thousands of people in the moment with the band and its music. And not one person is fucking texting.”

Would Oasis have been a stadium band had they started out now? “It would be mad to think that the first two records [Definitely Maybe and (What’s The Story) Morning Glory] would not transcend into a different era,” he replies. “So, I’d probably say yes, we’d be as big. But we were going for three years before we got signed, and we might not have made it to three years. Now, somebody could film you at a gig and go, ‘Nah, they’re shit,’ so maybe we wouldn’t have been given time to develop. Would we have got our foot in the door? Maybe not. But would we have been as successful? In any era, ‘Don’t Look Back In Anger’ and ‘Live Forever’ are going to be pretty special tunes.”

After walking away from the band in the aftermath of one row too many, he used the material he’d written for the eighth Oasis album as the basis of his first solo LP. Since then, he’s stayed true to his commitment to indulge his musical whims. In recent times, these have seen him add French female backing singers and a brass section to his High Flying Birds lineup, collaborate with the DJ, composer and producer Mr David Holmes and a French disco aficionado named The Reflex, and make a series of excellent groove-based EPs, a detour that he happily compares to Mr Paul Weller’s Style Council project. He’s even written material for Dizzee Rascal. “I don’t know what happened to that,” he adds. “Wrote, it, recorded it and sent off to him and haven’t heard back from him since.”

Perhaps most intriguing for fans of a certain vintage, though, is confirmation he’s working on a new track with another Manchester legend, Mr Shaun Ryder, formerly of the Happy Mondays and Black Grape. “Have you heard his new tunes?” asks Gallagher. “His new single is called ‘Mumbo Jumbo’ and it’s fucking outrageous. Outrageous. It’s not like anything he’s ever done.”

The plan to work together, which was facilitated by their mutual friend Mr Alan McGee, founder of Creation Records, was initially derailed when Ryder was struck down with Covid. The track is yet to be finished, but the early signs are promising enough for Gallagher to say he’ll likely release it as a standalone single. And what of Ryder, the seemingly indestructible embodiment of Madchester, the scene that bridged acid house and Britpop? “Shaun’s on great form,” he says.

The conversation rattles on through some colourful territory, including the thwarted plot to steal football (“The European Super League could only have come from the brain of an American, and VAR could only have come from the brain of a Swiss bureaucrat”), the evolution of his personal style (“You get over the midlife-crisis moment when you buy a fur coat and your trainers are more expensive than your mum’s house”) and British politics (“Boris Johnson has proved himself not to be the man for a crisis. Fancy getting Covid”).

Most surprising, though, is listening to Gallagher talk proudly about overseeing the decor for his new studio, which includes an artificial tree, framed prints of the Beatles, Mr Bob Dylan and Mr Sergio Agüero and, in a small room near the entrance, a one metre-square section of the dancefloor from Manchester’s Haçienda nightclub, mummified in bubble wrap.

“The dream,” he says of the studio, “is I can cycle here from my house in Maida Vale in half an hour. Turn up at midday, do a couple of hours, go for a boozy lunch. Smash it with the lads in town, come back pissed, do another couple of hours, then go and have some dinner. I want to get into that routine because I am a real creature of habit. If my routine is taken away from me, I actually find it difficult to function as a human being.”

He talks about thriving on deadlines set by his record label, which, I remind him, he owns. “Yeah, but if you’re not careful, having all the success and the money and the studio and the label, and being middle-aged and a guy and Mancunian, it becomes easier to put your feet up. Before, you know, five years will have passed and you’ll have got fat and you’ll have done fuck all. It works better for me if I’m really pushing myself.”

So, look out for Noel Gallagher this summer, pushing on through a boozy lunch, pushing the right buttons for a live audience somewhere or pushing himself on his mountain bike. “I’d be very easy to assassinate, trust me. MI5 would know very quickly that I like to cycle past the same shop at 11 minutes past 11 every fucking day.”

Back The Way We Came: Vol 1 (2011-2021) is out 11 June