THE JOURNAL

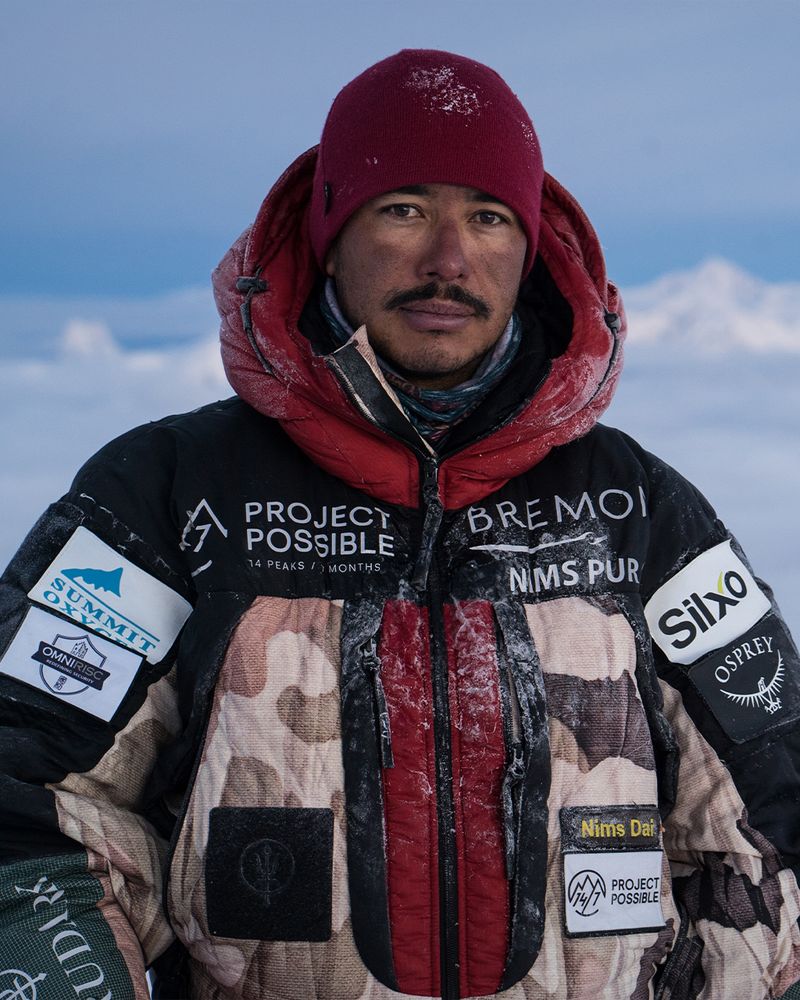

Mr Nirmal Purja and team, Manaslu, Gorkha, Nepal, September 2019. All photographs courtesy of Mr Nirmal Purja

At 8.58am, on 29 October 2019, after a gruelling 15-hour non-stop climb in howling winds, Mr Nirmal “Nims” Purja and his “Project Possible” team reached the summit of Shishapangma in Tibet.

It was done. Mr Purja – a Nepali and former special forces operative, then 36 – had climbed all 14 of the world’s 8,000m “death zone” mountains in a timespan of just six months and six days. The previous record stood at just shy of eight years. It marks a speed record so extreme that it instantly sent mountaineering into a new ultra-endurance era. That Mr Purja had only started climbing eight years earlier tells you something of his nature. “I’m not someone who just chills,” he deadpans.

What such a simple statistic – 189 days – can never express, of course, is the intensity of the personal highs and lows endured by Mr Purja along the way. In a word, it was “hardcore”, featuring the whole gamut of physical agony, sleep deprivation, military-grade logistics, daring rescues and even political lobbying. And each climb had its own distinct story arc.

In fact, just a few hours before reaching the final summit, there was nearly a terrible plot twist. Mr Purja had been holding up the rear to film drone footage of their final push. “The whole team were in front and this avalanche came and took me off. Obviously, that drone footage never came out,” he says with deliberate understatement. If he can laugh now at this particular near miss, earlier in the expedition there were times when the sheer weight of being the leader and figurehead of such an undertaking proved too much.

“At one point I was praying that an avalanche would come in and kill me,” he remembers. “Because then everything would be finished, everything done.”

What kept him going, he says, was reminding himself of the “motivating factors”; the reasons why he was doing it in the first place. First, “to show the world that anything is possible,” he says. Next, to raise the profile of Nepali climbers, by creating a crack team using only his fellow countrymen. “We have always been on the saddle,” he explains. And third, to raise awareness of climate change, evidence of which he has seen with his own eyes during his relatively brief climbing career.

The youngest of four sons, he grew up far from Nepal’s high mountains in the sub-tropical flatlands of Chitwan, where as a boy he would spend most of his weekend exploring the surrounding jungle. “I would definitely say I did have something different from other kids because I was so ambitious,” he says. “When I was in year nine, I used to wake up at three o’clock in the morning and do a 30km run. Then come back in to boarding school and pretend I’m sleeping in bed.”

He followed his father and two brothers into the Gurkha regiment of the British Army, a long-held dream, but soon set his sights on the special forces. After an arduous six-month trial, he became the first Gurkha to join the legendary Special Boat Service (SBS), the Royal Navy equivalent of the SAS, later becoming a cold-weather warfare specialist. It was partly after repeatedly being asked by non-Nepalis what Mount Everest was like and having to explain that he’d never been, that he decided to do a base camp trek while on leave. As soon as he got there he persuaded his guide to show him how to climb for real.

Mr Nirmal Purja at 8,070m on Mount Manaslu, Gorkha, Nepal, September 2019

“I’d done some crazy stuff in the special forces, and you think you’re invincible,” he says. “When I went to the big mountains, it put things into perspective. It made me realise how small we are.” It was on Dhualagiri in 2014, his first 8,000m summit, that he realised he also had a natural aptitude to be a high performer at altitude. “You can’t really say just because you were born in Nepal you are good at altitude,” he says in response to that stereotype. “Of course, I have something in my genes and I recover quickly. But mostly it’s because I’m happy; it’s massively down to your mindset as well.”

With the pull of the mountains getting stronger, he asked the SBS for leave to climb the five highest peaks in the world. When they declined, he decided to resign in 2019; six years short of a lucrative pension. “For a lot of people it was a crazy decision,” he says. “But you don’t take [money] with you when you die.” So, with no time constraints, he Googled the fastest time to climb all 14 of the 8,000m-high mountains. “And I said, ‘I could do that in seven months’. That’s where the idea came from.” Mr Purja remortgaged his house to help fund the first phase of six Nepali peaks. The sheer scale of the logistical challenge began to reveal itself, involving permits, transfers, equipment, team selection and, of course, funding. “Loads of friends were like, ‘why don’t you do it in 2020?’ Just imagine if I’d listened and taken their advice,” he says, referring to the effect the pandemic would have had on the attempt. “It’s a good example of never going for the second option just because it seems easier.”

As one of the toughest mountains of the entire 14 – and officially the deadliest with the highest ratio of deaths to successful summits – Annapurna was deliberately chosen first as a sink or swim trial for team selection. After successfully summiting, Mr Purja, who was also working as a guide to help fund the trip, celebrated with the team back at base camp before going to bed exhausted at around 3.00am. Not long after, news broke that a climber was in need of help below the summit. “I’ve never left anyone in the war. I wasn’t going to leave someone on a mountain that I’m on.” So he left his sleeping bag for a desperate rescue that involved being dangled from a helicopter by a rope. Two separate rescues followed on Kanchenjunga, which Mr Purja remembers as the lowest point of the entire project. Despite the team’s efforts there were no survivors. It’s for such situations that he says he carries oxygen.

Camp at Manaslu, Gorkha, Nepal, September 2019

In the mountains, what his military training provides above all else is performing under pressure. “What you get is, you’re trained to be able to operate in a very stressful environment, and still be able to make the right decisions,” he says. On Everest, he took a photo of the queue to the summit that went viral and was used as evidence of overcrowding on the mountain. “I’m very sad how the press has taken the negativity from that picture,” he says. “Sometimes, you only get one or two days on Everest when there’s a good weather window so of course everyone wants to summit.”

The team climbed the last three Nepali peaks in 48 hours for a total of six mountains in 31 days. With phase one complete, people were starting to take notice. It was here that watchmaker Bremont stepped in to officially support the remainder of the project. Phase two would bring a raft of new challenges, however. In 2013, the Taliban had killed 11 climbers at the base camp of Nanga Parbat and, with Mr Purja’s military background, the threat remained, so they decided to climb in secret, “using all my special forces tactics,” he says.

On the fearsome K2 – the world’s second highest mountain – in poor conditions the team fixed the ropes for the first summit of the season, therefore opening it up for a group of waiting climbers. The team also had to haul their equipment from one climb to the next. As the peaks came and went it soon became clear that the final tension would come from a most unlikely source: paperwork.

Shishapangma had been closed since 2013 because of avalanche risk and it took a concerted charm offensive, including calling in every contact he had back in Nepal, to help get it over the line. “It was a big moment,” he remembers, when he received a permit granting exclusive permission. His happiest moment came not on the summit but during the heroes’ welcome back in Kathmandu, which his seriously ill mother had been able to join. “My mum witnessed that, and was so happy that her son achieved something.

“I come from nowhere,” he says. “You don’t need to have opportunities given to you all the time. You can make things happen by yourself.”

His next project? “I can tell you but I’d have to kill you,” he jokes, before adding that it will be equally big and tough. Hard to imagine, perhaps, but we’ll certainly take his word for it. “This is only the beginning, buddy.”