THE JOURNAL

A small selection of the 100 colours offered by William Lockie

After 140 years, this renowned brand set deep in the Scottish Borders has hardly changed a thing – including the superlative quality.

Twenty years ago, a man only started to wear cashmere sweaters when he was old enough to pay for his own clothes. Although the high street is now flooded with cheap jumpers made from soft Mongolian goat hair, the knitwear crafted in the Scottish Borders town of Hawick retains an international cachet only matched by the best Savile Row suits, and the finest Jermyn Street shirts. This is why MR PORTER is so pleased to now stock sweaters from William Lockie, a family-owned manufacturer that’s been producing fine Scottish knitwear since the 19th century. To mark this occasion, understand what distinguishes the best Scottish cashmere, and for a rare glimpse inside the company’s factory, MR PORTER visited Hawick.

The view across Drumlanrig Square towards the factory, which opened in 1874

The firm’s premises, on Drumlanrig Square, haven’t moved since Mr William Lockie started his business in 1874, and the interiors appear unchanged since the 1950s. The global fashion industry feels very distant when you’re standing on the tartan carpet in the company’s offices, or drinking tea in its meeting rooms. The Borders’ lush green hills are visible in the distance, and the Slitrig Water (a small river) runs just behind the factory. Ducks swim on the clear river, which used to power the workshops, and crucially still provides the soft water in which every single William Lockie sweater is washed.

The River Teviot, which runs through Hawick

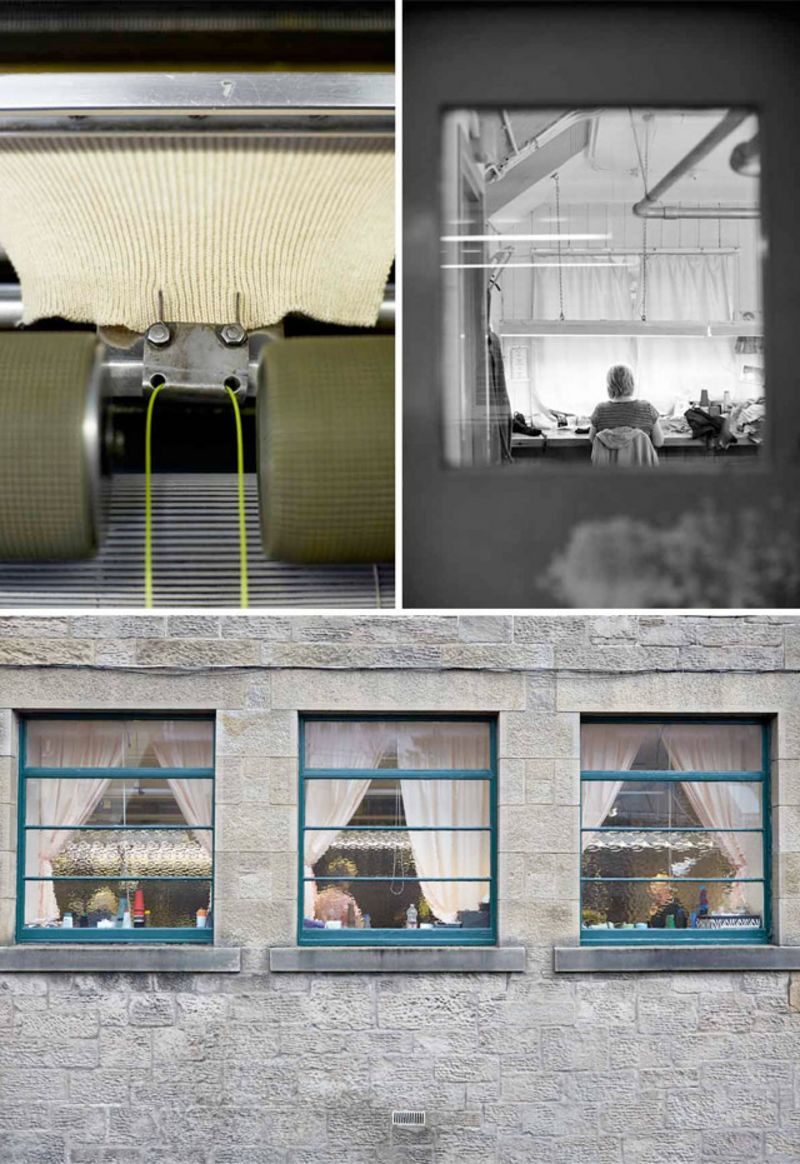

Stepping into the room where the sweaters are knitted is to be assaulted by the rhythmic clatter of light machinery. The eyes struggle to understand the knitting machines’ incessant tiny movements. What at first appears to be a series of different machines is, explains Mr Allan Gilchrist, William Lockie’s sales manager, one machine with eight “frames”, each of which produces one piece of knitwear at a time. “One machine can do different colours at the same time,” he says, “but it has to be the same size and pattern.” The knitting machines, some of which are more than half a century old, work to precise patterns inputted by old-fashioned punch cards.

The German-built knitting machines are more than half a century old, and the patterns are controlled by punch cards

Touching the pieces that come off these knitting machines (each crew-neck sweater is made up of nine separate fully fashioned pieces stitched together), they feel quite different from the feather-soft cashmere one expects. The reason, Mr Gilchrist reveals, is that the yarn for the sweaters is oiled by the spinners (the companies that turn raw cashmere into the colourful yarn that is fed into the knitting machines) so that it can stand up to the stresses of the knitting process. The single most important element of the sweaters, he says, is the quality of the yarn. “The cashmere we buy comes from Inner Mongolia. The best quality is spun and dyed in Scotland by Todd & Duncan in Kinross. We use the very best we can buy, and we’re putting a lot more cashmere into each sweater, and knitting them tighter.” This tension means that the sweaters hold their shape over time, even if hand-washed rather than dry-cleaned.

Bobbins of cashmere yarn, which are supplied by Scottish spinners Todd & Duncan. Handwork is present throughout the production process

Once the different pieces have been produced they are sent up to the workrooms, where the largely female workforce puts them together. This is done by hand, one sweater at a time, so good eyesight and nimble fingers are vital. Sometimes the handwork consists of putting the pieces onto sewing machines stitch by stitch, and sometimes it involves a pair of tailor’s shears and a piece of chalk, as when the neck holes are opened up. After the sweaters are sewn together (but before the collars are attached) they encounter the latest technology employed during the manufacturing process – washing machines. “It used to be done by hand in big troughs; now it’s done in quite new machines,” explains Mr Gilchrist. It takes 40 minutes at 40°, some detergent and that famously soft Scottish river water to remove the oil from the sweaters and reveal the hand-feel that’s cashmere’s defining quality. Mr Gilchrist says, “The more you wash a William Lockie sweater the softer it will get.”

The firm’s timeless premises have hardly changed in recent decades

After washing, the collars are attached, the sweaters are pressed and after a final quality check they’re ready for dispatch via UPS, which feels like a rare concession to 21st-century business practice given the timeless nature of the factory. It’s also the first time, since the delivery of the yarn, that another company is involved. As Mr Gilchrist says, “If anything goes wrong with a William Lockie sweater it’s William Lockie’s fault. We don’t farm anything out, everything is done in this factory.”

From the storeroom to the workroom the factory is defined by its skilful workforce

The result may be a niche business in comparison with the glory days of Hawick’s knitwear industry, but it’s one dedicated to combining handwork with the finest yarns to create the world’s best cashmere. That’s why, along with tartan and whisky, the reputation of this Scottish export remains undimmed.

The hills of the Scottish Borders are home to many sheep, but their wool is used for carpets, not sweaters