THE JOURNAL

You’re safe in Mr Murray Bartlett’s arms. A hug from the Australian actor is warm and assured, as comforting in places where physical touch is common as more apocalyptic settings. For example, in The Last Of Us, HBO’s latest hit, a big-budget, fungi-zombie video game adaptation, Bartlett plays opposite Mr Nick Offerman in the series’ virtuosic third episode. It’s a gutting two-hander that took a month to film and runs for nearly 80 minutes. “When we finished [a scene], he would smile and clap his arms around me and make me feel like I wasn’t a jackass,” says Offerman before evaluating Bartlett’s cuddle. “With me, his style is muscular and satisfying.”

The comedian Mr Rory Scovel experienced it for the first time outside a Beverly Hills bathroom at a cast dinner for the second series of Physical, the Apple TV+ show in which he and Bartlett starred, but had never met. “It truly just blew my mind,” he says. “I was like, really? Wow, we’re hugging. We’ve never said hello to each other. We’ve never spoken. And yet here we are in this embrace. There’s these hugs that make you feel kinda like a kid again. You’re protected.”

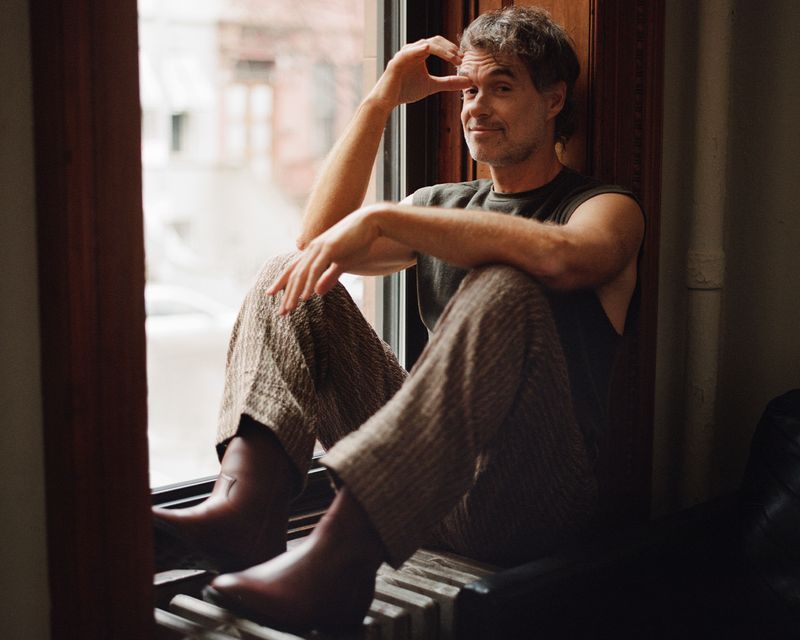

As we leave the MR PORTER photoshoot, Bartlett envelops a member of his PR team and says, “Love you, bye!” This is not the Bartlett we’ve seen on screen. His breakthrough performance was as Armond in The White Lotus, a hotel manager so fixated on maintaining control that a petty snipe with a guest escalates to total, self-induced ruin. For his work on the series, Bartlett was honoured with an Emmy, Critics Choice Award and an AACTA Award, the Australian equivalent of a Bafta.

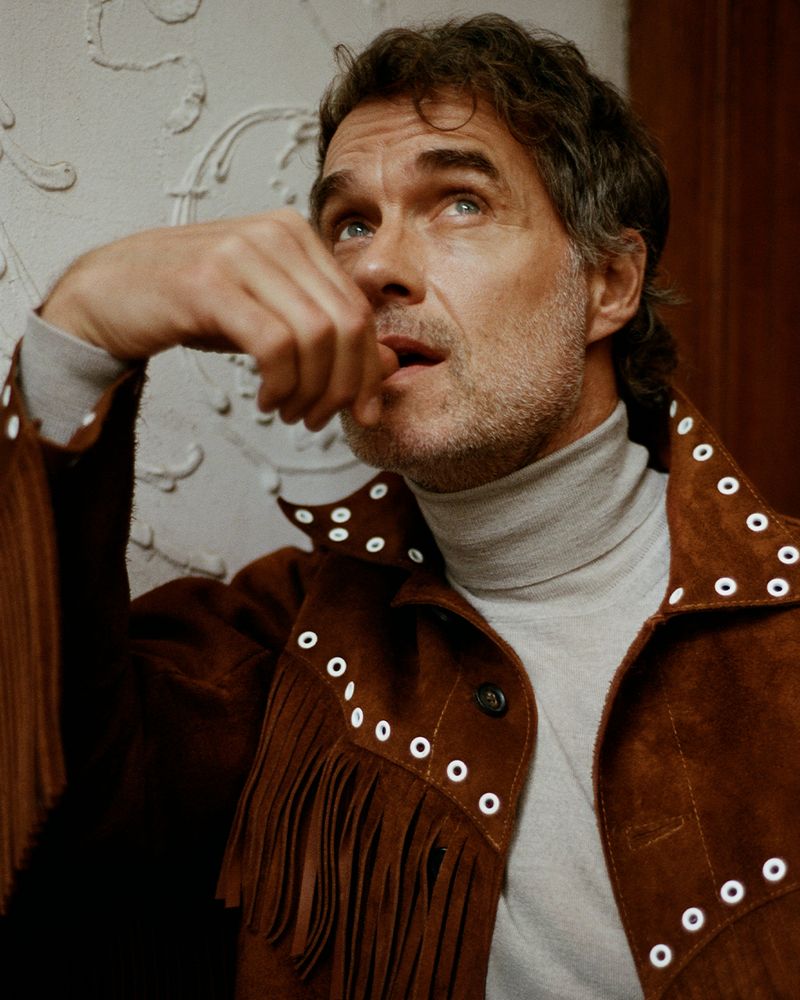

Subsequent roles were brilliant variations on the magnetic-but-potentially-dangerous theme. In 2021’s Physical, Bartlett played an aerobics guru with energy somewhere between the flamboyant fitness personality Mr Richard Simmons and Mr Mark Wahlberg’s character in Fear. In Hulu’s true-crime series Welcome To Chippendales, he portrays Mr Nick De Noia, the cocaine-motivated choreographer and producer who took male stripping worldwide, but goaded his business partner until the relationship deteriorated to the point where contract killers were called in to mediate the conflict.

In The Last Of Us, Bartlett and Offerman’s roles mirror their off-screen virile, alpha energy, which is deployed in a relationship dynamic I’ve never seen depicted on television before. When I suggest the part is an anomaly in Bartlett’s recent list of credits, he says he got the role before The White Lotus changed everything.

“I might have been the more subdued, handsome guy before,” he says, acknowledging the simple reality of his gorgeous face and the position in which he finds himself. “Now, a lot of people are like, ‘That’s the crazy guy.’”

Still, for the for first time in his career, the 51-year-old says, “I have choices. It’s huge. Choices like I’ve never had before. Even if I made bad choices, just the fact that I have choices is so exciting.”

“He is clearly a leading man,” Offerman says. “The whole package. And then the combination of that part [of Armond] with [The White Lotus creator] Mike White’s writing and [Murray’s] personality and his particular toolbox… The world said, ‘Holy cow. You’ve been running sprints all this time, but it turns out you’re an incredible pole vaulter.’”

Even when he gets a glowing review, Bartlett knows there’s a catch. “You can go from one set of expectations or projections into another set of expectations or projections.”

Bartlett learnt from his mother to approach life with unconditional love. She’s the kind of woman who waves until you are out of sight at the airport. She has spent the past few years winning over a pack of feral kangaroos, who come to the backyard of her rural Australian home to get food.

Bartlett’s mum stayed at home with him and his older brother for 14 years as a single parent. When she began her professional career, she worked mostly in welfare and non-profit services, a field into which Bartlett’s brother followed. He provides agricultural support to Aboriginal communities that have been displaced from their ancestral homes onto often inhospitable land, on which he also lives.

Bartlett serenely tells me his family history at an Eritrean-Ethiopian restaurant in the Harlem neighbourhood of upper Manhattan. The food is eaten utensil-free, so Bartlett’s spice-covered hands rest palm up and thumb to forefinger on the table between bites, as if he’s both mid-meal and yoga practice.

He waits as long as he needs to before speaking. Longer than anyone I’ve ever talked with. During these protracted quiet moments, I try not to move, often freezing with a handful with wet injera halfway to my mouth, in case my chewing disrupts his journey to the thought he’s trying to reach.

When I say Bartlett seems very comfortable with silence, he says, “What do you mean?”

Just that people generally feel compelled to speak after being asked a question.

“I was definitely a people pleaser earlier in my life,” he says. “And I just…” He pauses. “I feel like I’m much… I do a much better job of saying what I feel and think when I’m not afraid of digging a little bit… It’s weird that we think of silence as uncomfortable or awkward.”

A desire to please is one of the reasons Bartlett is not cross-legged in a yurt today, but instead doing press for what seems set to be another career-altering role – the premiere of The Last Of Us was watched by 4.7 million people. In between extolling the importance of maintaining inner peace and a caring community, Bartlett leans forward and pops his eyes open in waggish delight, the facial equivalent of the ah-OOH-ga horn.

He asks if I’ve read the Los Angeles Times piece about him that quoted Ms Emily Gordon, the actor Mr Kumail Nanjiani’s wife and the executive producer of Welcome To Chippendales. She said for the role of De Noia, “We need someone who both men and women want to have sex with, and nobody fits the bill better than Murray.”

Bartlett knows such declarations about his eminent bangability might never have been printed. In 2000, not for the first time, he contemplated leaving the entertainment industry because he wasn’t getting hired to tell the stories he found meaningful (or, sometimes, getting hired at all). He nearly absconded to the mountains of New Zealand to be a “woodsman”, a plan that at the time he found as plausible as the one he eventually chose: moving to New York City to be an actor.

From childhood, Bartlett says he had a sense that some calling would come. “Whatever I ended up doing to fulfil my potential, whatever that means. It’s a very vague thing, but I was like, ‘I want to fully do whatever I’m going to do.’ I did always have that feeling.”

He loved Australia, but he noticed that the people who stuck around seemed to be at arm’s length from the worldliness he saw in people who had left and accomplished something somewhere else. “It was a quality of people that had had the experience and become enriched versions of themselves,” Bartlett says. “I wanted to do that.”

He’s a man of love and nature, the son of a marsupial whisperer. He’s also dramatic, a showman, someone many men and women want to have sex with and slightly, deliciously bonkers.

“I do feel like there’s an Armond character living in my head,” he says. He and Armond know what it’s like to be someone obviously special, but thwarted in realising their potential – how many open spots for “someones” are there onscreen or in real life? Could you really imagine Bartlett playing (or being) a guy who never left his hometown? (As Nanjiani says, “With that bone structure?”)

Before Bartlett figured out how to harness and deploy his inner Armond, he tamped him down, feigning confidence. He kept being cast on not particularly notable projects as invulnerable men – the “subdued, handsome guy” parts he mentioned. It wasn’t until he actually felt confident that he started getting roles as vulnerable people, starting with Dom, the dominant third of a trio of queer men in HBO’s Looking, which ran from 2014 to 2015.

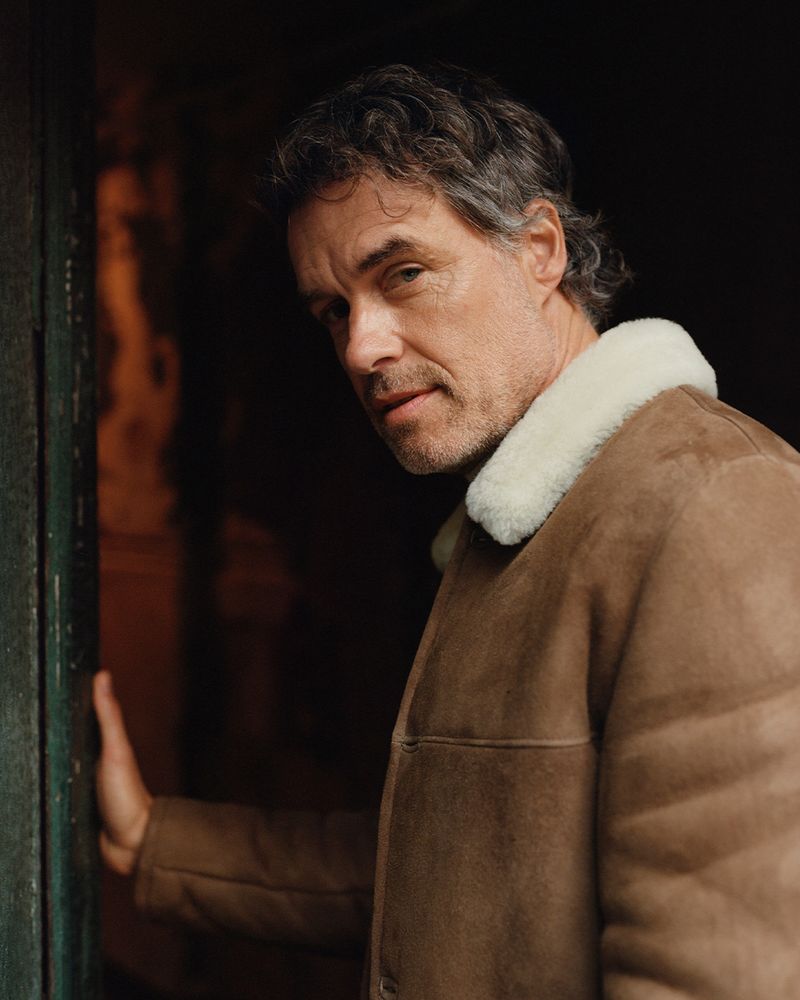

“He presents at first glance as sort of a more traditional masculinity, but he’s really not,” Nanjiani says. “There’s like a real softness at his core.”

Nanjiani explains his theory of why The White Lotus was an inflection point for Bartlett. “I think someone who looks like Murray, who’s just so handsome, watching someone like that spiral, it’s compelling in a different kind of way… You expect someone like that to be so put together.”

Murray’s greatest (and certainly recent) roles are disruptors. They come into an environment – a fitness studio, a hotel, a strip club – and alter the space. Without spoiling anything, in The Last Of Us, Murray fundamentally changes a situation from “surviving” to “living”.

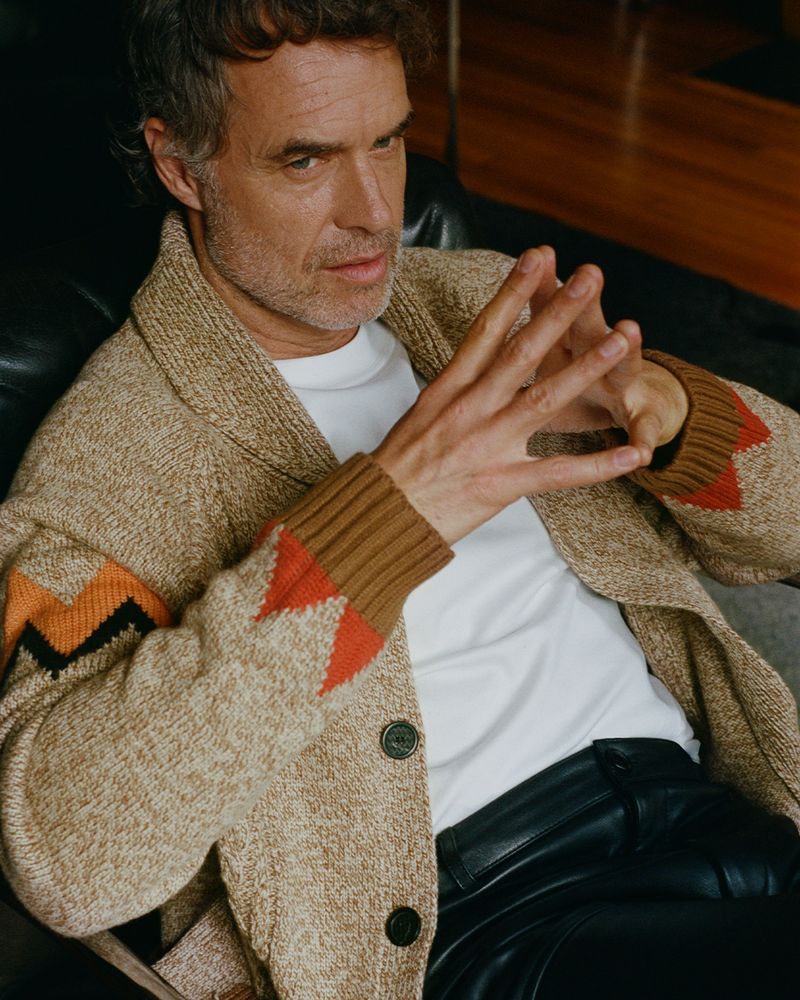

In his own life, Murray has found steadiness. “I’m a very emotional person,” he says. His partner is not. “One of the things I’ve found intriguing, and a little frustrating at times, is that he doesn’t sort of dive into the snake pit with me. In the beginning, I was like, ‘Come on! Come on in!’ And it was a little disorienting for me.”

Bartlett realised this was a boon. “I could be going through this tornado of emotions and then there’s this mountain right beside me and it’s like WHOOSH.” That “whoosh” is the sound of the little Armond in Bartlett’s brain being unable to disrupt his partner’s calm and eventually surrendering to it.

After 20 years of living in New York City, in late 2019, Bartlett moved with his partner and their lab-border collie rescue, Bo, to Provincetown, a small town on the Massachusetts coast. He wanted to be close to the natural world and he says his partner had a pre-pandemic prophecy: “I feel like something big is going to happen and I don’t want us to be living in the city.” Every day, Bartlett takes Bo for long walking meditations.

“There’s a simplicity to him,” Offerman says. “He has found the answers to what makes life enjoyable in a lot of ways. And those are simple. He lives in a beautiful place near the ocean. He loves books and his dog and his relationship. We always have to remember that everybody’s a human being and we all have to combat the same voices of dissent when we look in the mirror. But he’s made his mirror look awfully attractive.”

Bartlett licks his fingers and tells me about his upcoming projects: an indie film about an intersex person escaping a bad situation and an Apple TV+ series called Extrapolations, set in the environmental catastrophe humans have created and in which his scene partners are Ms Diane Lane and Mr Kit Harington. He’s writing a screenplay about a real event told through a fictional character’s story and would like to produce and star in the true story of a music industry professional turned activist who was murdered because of his work in the Amazon.

With every role, says Bartlett, “There’s something that I’m learning about myself, or there’s some sort of revelation in this character that might even be really uncomfortable, a looking-in-the-mirror moment. The key to unlocking a character, I think, is that it’s a sort of exorcism or has some therapeutic element to it.”

I ask what that uncomfortable thing was for Frank, Bartlett’s role in The Last Of Us. He stops speaking for nearly a full minute. His eyes start in their familiar resting spot, down and to the right. Then he looks up at me and even though I’ve been watching him the whole, endless time, I can’t understand how he could have got here so quickly, emotionally teleporting from upcoming work to weeping. Because now Bartlett is crying, faster than he can wipe away his tears. “He finds what we were talking about,” he says, returning to his partner. “Stability and an anchor point in his life, when I was finding that [in mine].”

We say goodbye so Bartlett can head to Williamsburg to meet his mountain for dinner. But before he leaves, he turns and holds out his arms.

The Last Of Us is on HBO/Sky Atlantic now