THE JOURNAL

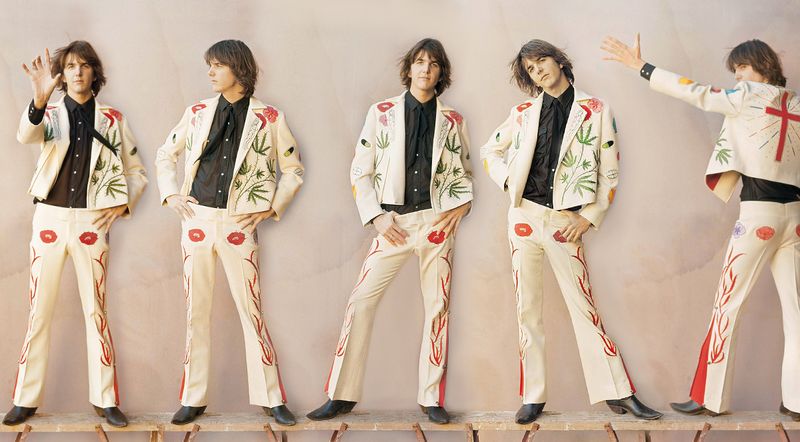

Mr Parsons’ studio portrait in California, 1969 Jim McCrary/ Redferns/ Getty Images

Narcotics, Nudie Cohn suits and The Rolling Stones – we pay homage to the alt-country pioneer, whose demise was as rock’n’roll as his career.

To Miss Mercy of Mr Frank Zappa’s LA protégées Girls Together Outrageously (aka the GTOs), Mr Gram Parsons was “true glitter-glamour rock”. The phrase might sound odd when applied to a guy regarded as the founder of “alternative country” – and who himself referred to 1970s glitter as “litter rock” – but it’s hardly wide of the mark when you look at photographs of Mr Parsons in his late-1960s prime, sporting a bright white suit designed by the great LA-based rodeo tailor Mr Nudie Cohn and bedecked with rhinestone pills and marijuana leaves.

Glitteringly glamorous Mr Parsons could certainly be. He took the gaudy sparkle of Nashville’s Grand Ole Opry stars and fused it with the wasted foppery of his pals The Rolling Stones in their Boho-aristo pomp. He combined the Southern sex appeal of his teen idol Mr Elvis Presley with the sybaritic androgyny of Sir Mick Jagger in Nic Roeg’s Performance – a film he watched many times – and created a unique style that’s influenced a hundred musical renegades, from Messrs Ryan Adams to Bobby Gillespie.

“It’s funny when you look back at how he was wearing these outlandish scarves and doing this mild cross-dressing,” said bass player and mandolinist Mr Chris Hillman, who formed The Flying Burrito Brothers with Mr Parsons in late 1968. “Here we were playing these redneck country bars where people just wanted to kill us.”

“If Mr Parsons wasn’t the first 1960s musician to attempt the apparently impossible – making country music hip – he was arguably the coolest, sexiest and most influential of them”

Mr Hillman had already watched Mr Parsons antagonise country fans when, in March 1968, they played the Opry together in The Byrds, the LA folk-rock band that had set the Sunset Strip alight with their 1965 version of Mr Bob Dylan’s “Mr Tambourine Man”. “Tweet tweet!” carped one Nashvillite when the LA longhairs took the Opry stage. But the prejudice worked both ways. When Mr Perry Richardson, assistant to the Stones’ photographer Mr Michael Cooper, was asked to look after Mr Parsons during a trip to London, he was astonished by his first sight of the svelte rock star when he showed up at his Holland Park flat. “I had a picture in my head of a little squat country and western singer,” Mr Richardson remembered. “Gram turned up in yellow trousers and a jean jacket.”

If Mr Parsons wasn’t the first 1960s musician to attempt the apparently impossible – making country music hip – he was arguably the coolest, sexiest and most influential of them. Los Angeles may have had its fair share of musicians turning the reactionary squareness of country on its head – from Mr Rick Nelson to the Fantastic Expedition of Messrs Doug Dillard and Gene Clark – but none was quite like Mr Parsons.

From left: Messrs Pete Kleinow, Chris Ethridge, Parsons and Hillman of The Flying Burrito Brothers in their Nudie suits as they pose with two female fans in front of a Joshua tree, Joshua Tree, California, 1969 Michael Ochs Archives/ Getty Images

The background of the boy born Master Ingram Cecil Connor III – he eventually took his surname from stepfather Mr Robert Parsons – was closer to the characters of Mr Tennessee Williams than it was to the sounds of Sunset Strip. “He was a good kid, with a good heart,” Mr Hillman told me. “If you delve into his background, though, it’s pure Southern Gothic.” A nine-year-old Mr Parsons saw Mr Presley at the Waycross City Auditorium in 1956 and never looked back. Mr Parsons’ mother Ms Avis Snively was the daughter of Mr John Snively, founder of Florida’s biggest citrus growers, and a chronic alcoholic; his real father, Mr “Coon Dog” Connor – a Snively employee – killed himself in 1958. Moving with Ms Snively and her second husband from Georgia to Winter Haven, Florida, young Mr Parsons strutted his stuff in local rock’n’roll bands before leaping aboard the folk bandwagon of the early 1960s. Though he spent a semester at Harvard, academia was swiftly abandoned in favour of Gram Parsons & The Like, a group bankrolled by his annual trust fund of $30,000 and housed by him in a large house in the Bronx.

Mr Parsons’ vision of what he called “soul-country-cosmic” music – fuelled by acid trips taken in Vermont with former child actor Mr Brandon De Wilde – took shape when The Like evolved into the groovier-named International Submarine Band. Visiting Mr De Wilde in Los Angeles for the first time in late 1966, Mr Parsons fell in love with both the city and Mr David Crosby’s girlfriend Ms Nancy Lee Ross. Soon he was holed up with Ms Ross on Hollywood’s Sweetzer Avenue and infiltrating the buzzy local pop scene. “Everybody was in love with him at this point,” the great LA writer Ms Eve Babitz recalled. “He was like a kind of F. Scott Fitzgerald hero in a place where nobody had ever heard of Fitzgerald except him. He’d be wearing white duck pants and a navy blue blazer, and he was as cute as Elvis.”

The Submarine Band was summoned to southern California and appeared in Mr Roger Corman’s 1967 classic psychsploitation film The Trip. Mr Parsons then persuaded Ms Nancy Sinatra’s former singing partner Mr Lee Hazlewood to release a Submarine Band album on his LHI label. Though it included songs by Messrs Johnny Cash and Merle Haggard – and has some claim to being the first true country-rock album – 1968’s Safe at Home wasn’t a patch on the same year’s Sweetheart of the Rodeo, the seminal country-rock album by The Byrds that featured Mr Parsons as Mr Crosby’s replacement.

With Sweetheart’s pining “Hickory Wind” (a song written on a train ride from Florida to LA), Mr Parsons found his true niche as a singer and a songwriter. He was now immersed in the music not just of Nashville but of California itself, to the point where he borrowed and customised the look of Bakersfield country and western star Mr Buck Owens by having his first suit made by legendary LA rodeo tailor Mr Nuta “Nudie Cohn” Kotlyarenko. That number featured naked women, pills and marijuana plants and was a brilliant subversion of the iconography of Western attire.

“Mr Richards was both the making and the unmaking of Mr Parsons. He fell in love with the Stones and embarked on a musical love affair with ‘Keef’”

Then along came Rolling Stones guitarist Mr Keith Richards, who was both the making and the unmaking of Mr Parsons. After a Byrds show in London in July 1968, when he joined the Stones on a late-night visit to Stonehenge, Mr Parsons embarked on a musical love affair with “Keef”. The tradeoff was a simple one: Mr Parsons was seduced by Mr Richards’ outlaw cool, Mr Richards by Mr Parsons’ Southern charm and deep knowledge of country. Rich-kid dilettante that he was, Mr Parsons immediately jumped ship from The Byrds, claiming Mr Richards and Ms Anita Pallenberg had urged him not to travel to South Africa with the group. The bromance continued when Mr Richards and Ms Pallenberg came to LA to finish work on the Stones’ Let It Bleed. “Keith came in with Anita and this skinny Southern boy in crushed velour trousers and silk scarves,” recalled Mr Phil Kaufman, then working as a Jagger-styled “executive nanny” for the Stones. “They went out and spent a lot of money on country records, and I would sit there and play DJ.”

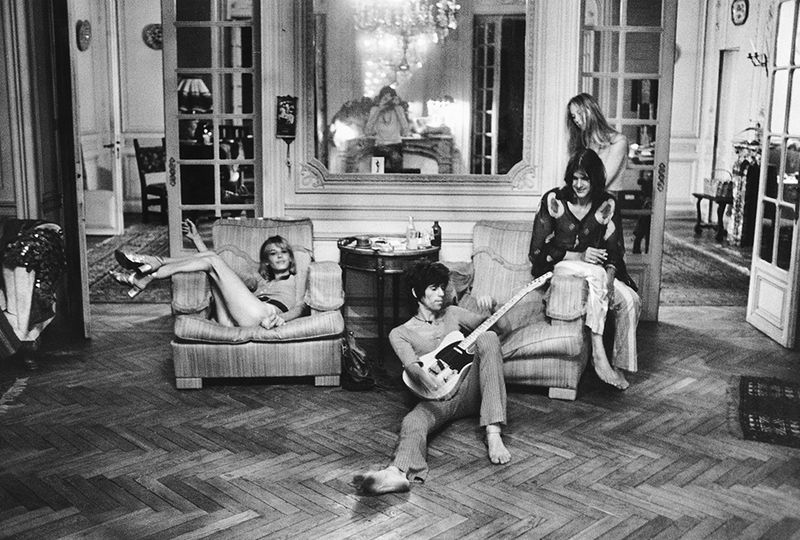

From left: Messrs Richards, Parsons and Phil Kauffman, Ms Anita Pallenberg and Mr Tony Foutz, LA, California, 1969 © Michael Cooper Collection

“Gram was just like a puppy dog with them,” Mr Chris Hillman remembered. “It was sort of embarrassing, like bringing your kid brother along on a date.” But Mr Hillman was forgiving enough to form The Flying Burrito Brothers with Mr Parsons after he too departed The Byrds. He also knew that Mr Parsons was the real deal, blessed with authentic talent as both a writer and singer. The songs they wrote together for the Burritos’ 1969 debut The Gilded Palace of Sin – “Sin City”, “Christine’s Tune” and more – were the most convincing manifestation yet of Mr Parsons’ cosmic Americana. The images of him at this time, with long hair and eyeliner, capture him at his coolest and prettiest. No wonder the patrons of such San Fernando Valley dives as the Palomino yelled “Goddamn queers!” at the sight of them.

Mr Richards, who saw him play the Palomino – and who was briefly contracted to produce The Flying Burritos – subsequently co-wrote a bunch of Parsons-influenced Stones songs that included “Wild Horses”. He played the aching ballad from Sticky Fingers to Mr Parsons after the Stones’ ill-fated performance at Altamont , when Hell’s Angels “security men” stabbed a young African-American fan to death right in front of the band. “Gram kind of redefined the possibilities of country for me,” Mr Richards told me in 1997. “There are certain songs where I hear him and I think, ‘Shit, I just did Gram’.”

From left: Ms Anita Pallenberg, Messrs Richards and Parsons, and Ms Burrell (just seen) at the Villa Nellcôte in Villefranche-sur-Mer, France, 1971 Photo Dominique Tarle courtesy La Galerie de l’Instant

Mr Parsons’ troubled past was always going to catch up with him. “Here was a kid with a lot of talent but zero discipline,” said Mr Hillman, who eventually had to sack Mr Parsons from his own band. “Suddenly he had one foot in country music and the other in the rock’n’roll glamour world.” Compounding the problem was Sir Mick Jagger’s jealousy of the Messrs Richards-Parsons bond. When Mr Parsons and teenage girlfriend Ms Gretchen Burrell joined the Stones’ circus in their Côte d’Azur tax-exile, they were quickly asked to leave. “I really don’t remember the circumstances of the departure clearly,” Mr Richards noted disingenuously in his bestselling Life. “I had insulated myself against the dramas of the crowded household.”

Back in California, Mr Parsons moved into Sunset Boulevard’s Chateau Marmont hotel – then a den if not a gilded palace of iniquity – and began running around with fellow rich kid Mr Terry Melcher, son of Ms Doris Day and producer of The Byrds. “Gram thought he was too much of an artist to be understood by the industry,” Mr Melcher said later. “He was one of these people who thought it was great to die young.” At the Chateau, Mr Parsons forsook heroin but drowned himself in tequila, becoming unfashionably fat in the process. Yet somehow he bestirred himself again, possibly motivated by the Top 40 of the Eagles, who’d smoothed the bittersweet pain of his alt-country music into massive commercial success. “Nobody gave a shit about Gram, he never sold any records,” said Ms Pamela Des Barres, another of Mr Zappa’s GTOs. “No one took him seriously except people such as Don Henley, who was definitely watching him.”

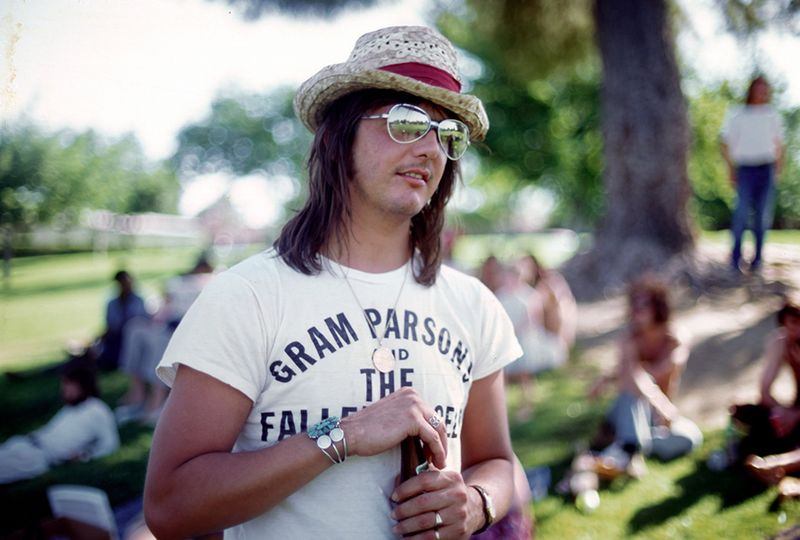

Redemption came for Mr Parsons via a folk singer he heard in October 1971 in a Washington DC bar called Clyde’s: a year later – playing Conway Twitty to her Loretta Lynn – he flew Ms Emmylou Harris to California for the sessions that produced 1973’s wonderful GP. The backup musicians – paid for out of Mr Parsons’ own pocket – included the core sidemen who played behind Mr Presley in Las Vegas. (They also played on Mr Parsons’ posthumous and equally gorgeous 1974 album Grievous Angel.) “It all seemed pretty chaotic to me,” Ms Harris confessed to me 40 years after the GP sessions. “Gram was drinking off and on throughout the sessions, but he was such a sweet, generous, kind person. There was no meanness in him at all.” In the spring of 1973, Ms Harris set off with Mr Parsons and road band The Fallen Angels on a tour that took them from Boulder to New York City. “I really felt Gram was on a road to recovery through the tour we did,” she said. “The drinking was going away and the fog was lifting.”

Mr Parsons at a party in the park, LA, California, 1973 Ginny Winn/ Michael Ochs Archives/ Getty Images

Clearly it didn’t lift high enough. Mr Parsons had just filed for divorce from Ms Burrell when, in the early autumn of 1973, he drove out to the California desert town of Joshua Tree with three drug buddies. He overdosed on heroin on the night of 18 September and was pronounced dead in the early hours of the next morning. “He’d cleaned up, and that was the reason he died,” said Mr Richards. “He was clean and took a strong shot. It’s the one mistake you don’t want to make.”

Mr Phil Kaufman – by now The Fallen Angels’ road manager – honoured Mr Parsons’ express wishes when he intercepted the singer’s casket at Van Nuys Airport and drove it back to Joshua Tree in a hearse. There at Cap Rock – where Mr Parsons had once spent a peyote-fuelled night with Messrs Richards and Pallenberg – Mr Kaufman soaked the corpse with gasoline and dropped a lit match on it. In the starry darkness of the desert night, the flames lit up Cap Rock like illuminations.

“Only in the 1980s, with the first hints of the Americana movement in that decade’s ‘cowpunk’ movement, did a significant reappraisal of Mr Parsons’ work begin ”

For a decade after his passing, Mr Parsons was woefully neglected. Only in the 1980s, with the first hints of the Americana associated with that decade’s “cowpunk” movement, did a significant reappraisal of Mr Parsons’ work begin. The privileged decadence that had long counted against him now seemed alluring and tragically romantic. When Ms Harris released the Gram-saturated Ballad of Sally Rose album in 1985 – and fans such as Mr Elvis Costello started speaking up – the legend was under way. Few now doubt just how great – and how iconic – Mr Parsons was.

In the last interview he ever gave, Mr Parsons told Crawdaddy! magazine that he spent a lot of time at Joshua Tree, “just looking at the San Andreas fault and thinking to myself, ‘I wish I was a bird drifting above it’”. When his hour of darkness came upon him, he certainly got his wish.

Mr Barney Hoskyns is the co-founder and editorial director of online archive Rock’s Backpages and the author of – among other books – Hotel California: Singer-Songwriters and Cocaine Cowboys in the LA Canyons_._