THE JOURNAL

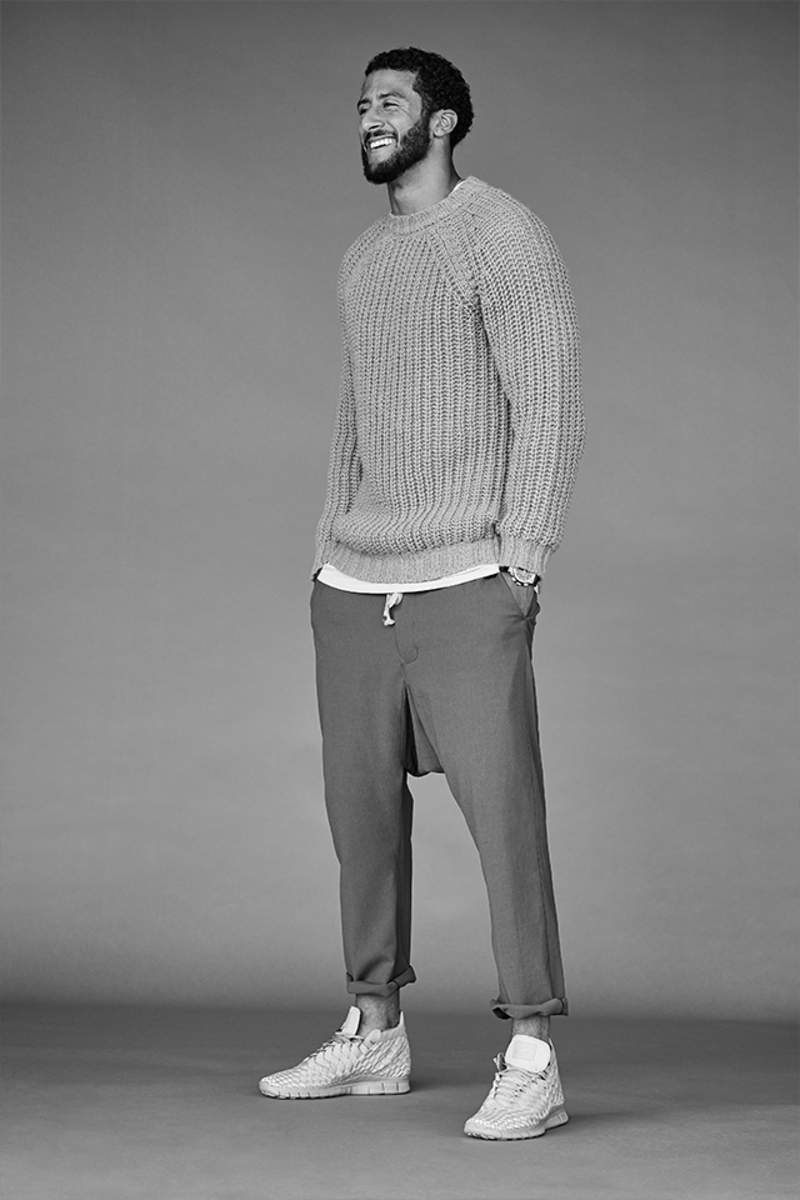

The San Francisco 49ers quarterback on bucking expectations, riding out the haters and how he does it all with a healthy dose of style.

It’s a heck of a day to meet up with Mr Colin Kaepernick, the outlandishly gifted quarterback and a man who many in the San Francisco Bay Area hoped would bring a Super Bowl win to the city. The reason? Just recently (the last Sunday in September), he turned in a performance that was – how to say it politely – the ugliest outing of his career, a 40-point beat-down at the hands of the Arizona Cardinals. Still, he is a gentleman – a man who on most days is as elegant off the field as he is on it – who greets me warmly and willingly talks about, um… style. Even though this will undoubtedly set off the “talking heads” on AM sports radio.

To him, style is not simply about clothing. It is about how one faces the world – good day or bad. Or as he puts it: “From a young age, my dad, being a businessman, constantly talked to me about carrying myself in a certain way and treating people with respect. And I think that’s something that’s carried over throughout my life. It’s how I deal with certain situations.”

By necessity, Mr Kaepernick has been thinking all his life about how other people read and misread him, and why. Long before his neon talent on the fields captured sports fans’ attention, he stood apart. (And yes, it is “fields” plural because as a teenager, he threw a 95-mile-per-hour fastball and was considered a better baseball than football prospect.) To a large degree, this misreading of who he is can be explained by the fact that he is the biological son of a black man and a white woman from Milwaukee, and the adopted-from-birth son of Mr Rick and Ms Teresa Kaepernick – lily-white Wisconsin cheese makers who relocated to California four years after Colin was born.

Even before he was old enough to describe them, Mr Kaepernick had two guiding feelings. The first, simply, was that “I knew I was different to my parents and my older brother and sister.” The second was less of a feeling than the absence of one: “I never felt that I was supposed to be white. Or black, either. My parents just wanted to let me be who I needed to be.” The world, of course, was less abiding in its notions of what a brown-skinned boy, standing out in bold relief against a uniformly white background, ought to be. This made him conscious of his posture, both literal and figurative, from an early age. “We used to go on these summer driving vacations and stay at motels,” Mr Kaepernick recalls. “And every year, in the lobby of every motel, the same thing always happened, and it only got worse as I got older and taller. It didn’t matter how close I stood to my family, somebody would walk up to me, a real nervous manager, and say: ‘Excuse me. Is there something I can help you with?’”

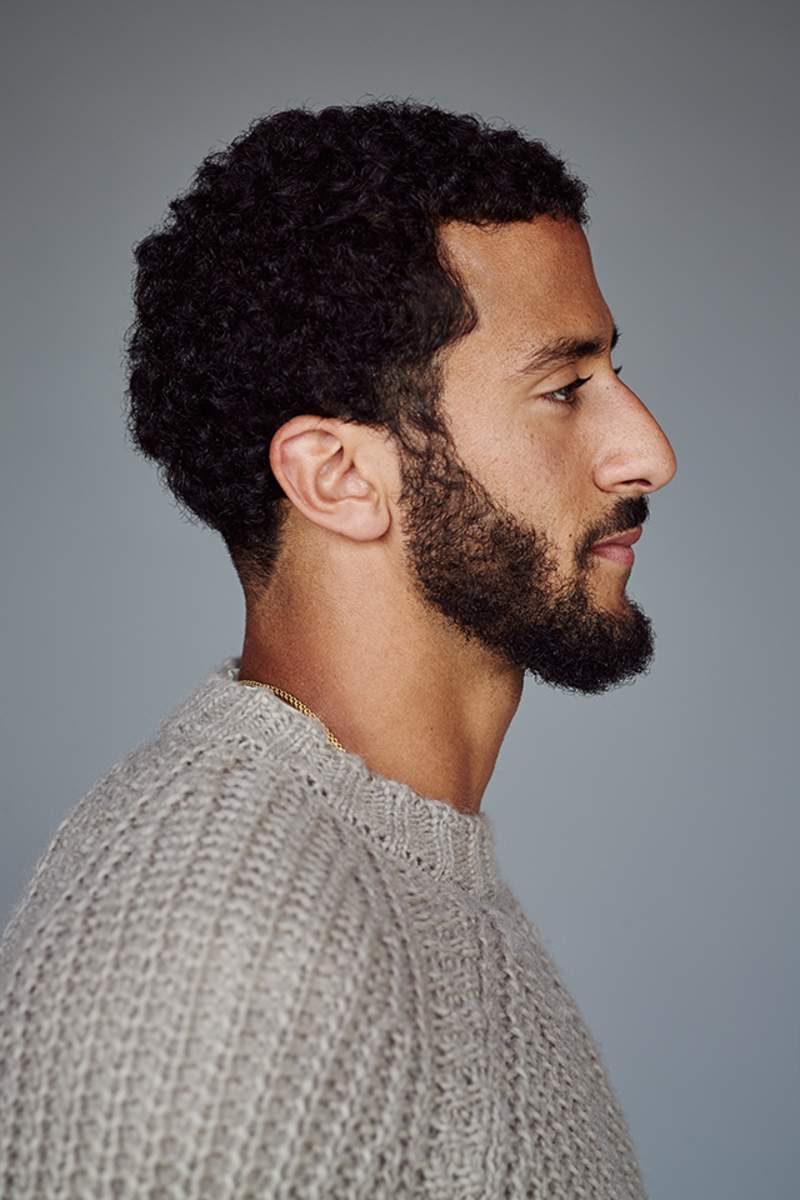

It’s tempting to comprehend his backstory as the stuff of the past. Formative and informative, yes, but history. Except that it’s not. The semiotics of Mr Kaepernick, who is now 27, didn’t stop discomfiting people once he became a household name in America. Instead, he entered a whole new (actually, old) world of racial coding. The first salvo came three weeks after he took over as San Francisco’s “starter” in the autumn of 2012, in the form of a Sporting News column: “Approximately 98.7 per cent of the inmates at California’s State Prison have tattoos. There’s a reason for that. NFL quarterback is the ultimate position of influence and responsibility. He is the CEO of a high-profile organisation, and you don’t want your CEO to look like he’s just got paroled.” The article and the “controversy” it generated made Mr Kaepernick’s tattoos iconic. Like many articles in the same vein that followed, it omitted the fact that all but a few of Kap’s tats quote Psalms and praise God. (He prays before he eats his meals and says his prayers at bedtime, too.)

“It’s funny about the tattoos,” Mr Kaepernick says. “I got interested in getting inked back in college, long before I really started to think about fashion and clothes and how I put myself together in public. I just got interested in tattoos because I liked the way they looked – to me. Nothing about them was for ‘show’. It was only when other people decided they ‘said’ something that I started Kaepernicking [nomenclature for his ritualistic kissing of his bicep tattoos after touchdown plays].” He is quick to add, “To be honest, I almost have more respect for that man [writing on Sporting News] saying what he felt, instead of trying to code it as ‘he’s a raw athlete’.”

"My racial heritage is something I want people to be well aware of. I do want to be a representative of the African community, and I want to hold myself and dress myself in a way that reflects that."

The loss to the Cardinals only caused the re-posing of vaguely racist questions that have stalked Mr Kaepernick for most of his career: is this quarterback a “student of the game” or a “raw talent?” Is he a general who wages the game with his head and his passing arm, or a test pilot who’s all speed and juke? The question should have been put to rest in his debut playoff game two years ago: he’s both. In that game he “strafed” the Green Bay Packers from the air while also rushing for two TDs and 181 yards – an NFL record for a quarterback.

Wrestling with the labels that outsiders put upon him fuelled his interest in style, in clothes, and in labels that come from Paris and Milan. “My interest in fashion probably would have developed anyway,” he continues. “But all this stuff made me ask myself in a really focused way: ‘What do I represent?’ And you know what? My racial heritage is something I want people to be well aware of. I do want to be a representative of the African community, and I want to hold myself and dress myself in a way that reflects that. I want black kids to see me and think: ‘OK, he’s carrying himself as a black man, and that’s how a black man should carry himself.’”

"I don’t want something I wear to scream at people when I walk into a room—but I also don’t want to blend in with the wall.”

In the States, professional basketball has a long tradition of players dressing well and showing an individual sense of style. Mr Kaepernick and others, including Mr Victor Cruz, are at the forefront of a generation of American footballers who are not only interested in dressing well, but in using fashion to communicate an identity that is larger than self.

So what does that mean specifically in terms of wardrobe? “Firstly, it means thinking about the time, a place and situation I’m dressing for. That said, I like things that stand out – but that also are very clean.”

Clean? “For the most part, the things I wear are pretty simple in terms of how the pieces go together. But there might be a piece here or there within that outfit that makes it ‘pop’. It’s about balance. I don’t want something I wear to scream at people when I walk into a room, but I also don’t want to blend in with the wall.” Imagine those words dropping from the mouth of Mr Joe Montana, the 49ers quarterback whose four Super Bowl wins make him the gold standard for the franchise.

That said, there’s a final question that needs asking. Mr Kaepernick glided up to our meet in a pearly-white Jaguar, parked, then emerged with ‘pop’. A casual tee. Red team shorts. Red Nikes. Blue, nearly knee-high socks adorned with cartoon piggies in cop uniforms. And on top – less than a day after a four-interception debacle that has the San Francisco Bay Area sports media calling for his head – a black knit cap with white block lettering that reads “RECKLESS”.

“So, what’s the pop here? The socks or the lid?” I ask. But this 6ft 4in biracial Adonis, who finished his senior year of high school with a 4.5 grade point average, isn’t about to do my reading for me. “Know what?” he says, levelling a shy smile. “I think I’ll let you figure that one out for yourself.”