THE JOURNAL

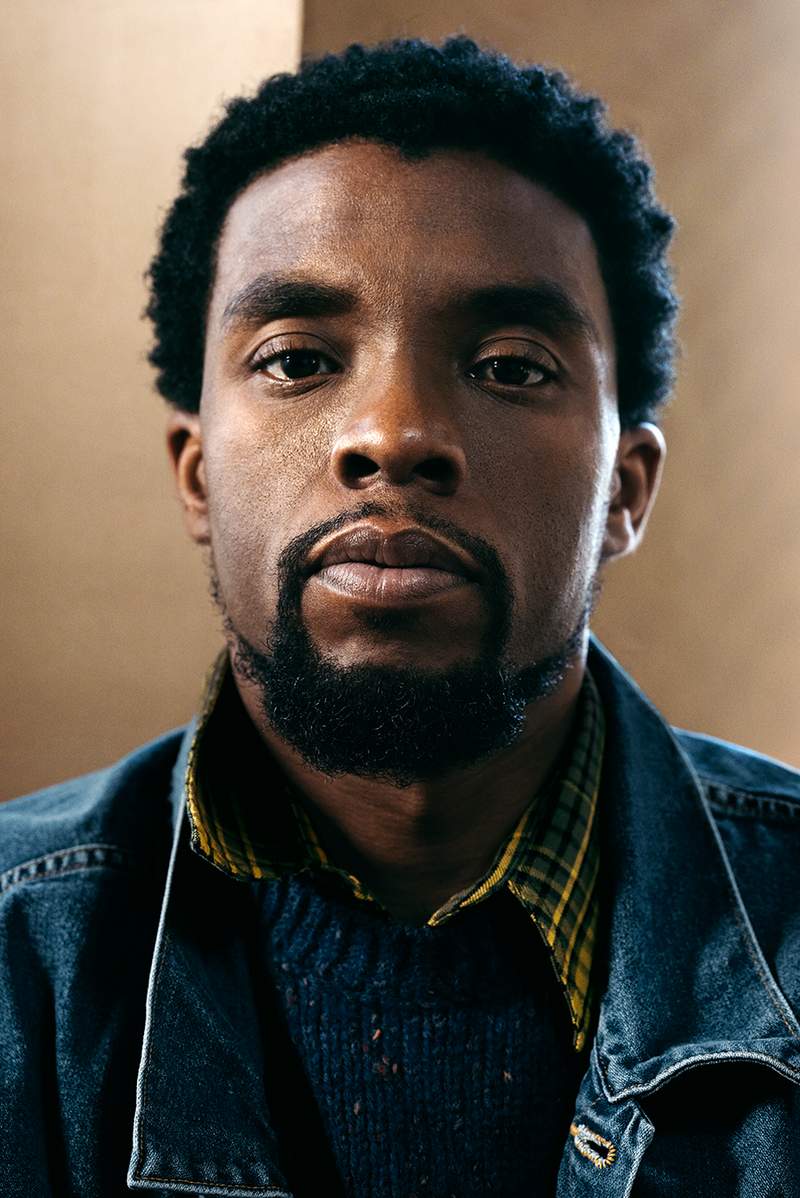

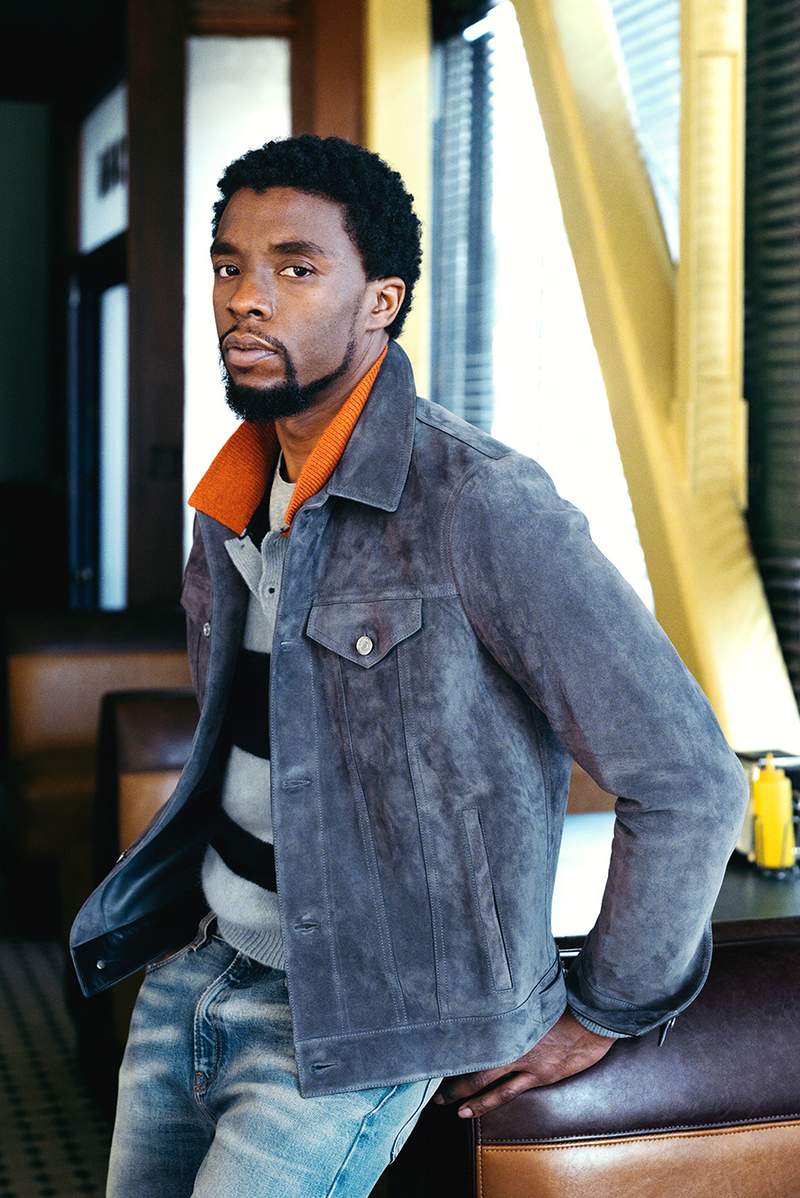

It’s the mid-afternoon lull at Sage, a vegan café in Echo Park, a hipster part of Los Angeles, and Mr Chadwick Boseman is sitting at a corner table, sipping a “greena colada” and considering the cauliflower wings. These days, he’s “mostly vegan” and an avid juicer. No one seems to have spotted him so far. To the casual observer, we’re just a couple of regular guys whiling away an afternoon.

Except we’re not. One of us is about to be big news. One of us is on the cusp of such global celebrity that he even has his own action figure. Although you probably haven’t heard of him yet.

“Yeah, it’s a weird feeling,” he says, grinning. “Some [of the action figures] look generic, but man, I’ve seen a couple of them that are like, ‘That’s me.’ I can’t have them on my shelf. I just give that stuff away.”

Mr Boseman is playing the Black Panther, the first black superhero to lead his own movie in the Marvel Cinematic Universe, and has signed up for five films that follow it, including the next in the Avengers saga.

Superhero movies dominate the box office as it is. And this release is set against a backdrop of #OscarsSoWhite, the widespread protests in the US against Confederate monuments and police brutality against black people, the neo-Nazi rally in Charlottesville and the president’s controversial reaction to it, and NFL star Mr Colin Kaepernick’s hotly debated decision to “take the knee” during the playing of the US national anthem. One could argue that in such times as these, the first black superhero movie has greater resonance. Beyond just a cinematic milestone, is this part of a cultural and political “moment”?

Mr Boseman grimaces. “Yeah, I hope so. But I hesitate to jump on that ‘Oh, it’s a movement’ thing. Because it depends on how it opens. I mean, it’s got to happen first, right?” He laughs. “People need to show up and not bootleg it.”

As superheroes go, Mr Boseman is remarkably low-key. He’s slim like a dancer, quietly spoken and unassuming. He answers all questions carefully, speaking slowly, taking his time. Now 41, he sprang from obscurity some five years ago, when he began an extraordinary run of roles as black American icons. First he was Mr Jackie Robinson, the first black superstar baseball player, in 42. Then he was the godfather of soul Mr James Brown in Get On Up. And most recently, he portrayed Mr Thurgood Marshall, the first ever black Supreme Court justice, in Marshall. His superpower, it seemed, was black biopics – he was Biopic Man.

In Black Panther, he plays King T’Challa, the leader of Wakanda, an unconquered and advanced African nation. And T’Challa is an altogether more imposing presence. While Mr Boseman is tactile and loose, tapping me on the arm and shoulder, pointing and gesturing “like I’m doing a hip-hop beat”, T’Challa is the opposite. “I studied that quiet strength, how the body exudes it,” he says. “I looked at Masai warriors, I watched the Shaka Zulu movies. And other leaders like Patrice Lumumba [the Congolese independence leader]. Obama. I listened to Mandela’s speeches in my trailer.”

Mr Boseman is a Black Panther fanboy. He explains how the interpretations vary from era to era. How the 1990s version gave T’Challa’s bodyguards lighter skin and straight hair, because “that’s what people thought fine women looked like at the time”. How the 2000s version had more of a hip-hop pride. “He was winning fights, he never got beat.” Mr Boseman had long dreamed of playing the part himself. He’d even dream about possible storylines and write them in his journal.

And in true superhero style, destiny appears to have conspired to win him the role. “Yeah, I had some experiences. You could call them cosmic or whatever,” he says, matter of factly.

For instance, on a trip to the sacred site of Machu Picchu in Peru, he noticed the symbol for the puma on the cross there and thought instantly of Wakanda, “another lost city in the jungle”. When in Australia shooting Gods Of Egypt – one of his less well received films – a security guard put a Black Panther comic book in his trailer, apropos of nothing. “I didn’t once mention the character, but he was like, ‘Hey, I think you’re going to play this one day.’ It’s crazy.”

And when the call came, the signs continued. He was in Zurich, about to walk the red carpet for the premiere of Get On Up, when his agent called to say that Marvel’s bigwigs wanted to speak with him – “now!”. So Mr Boseman sped through the red-carpet photos and had the limo drive him around so that he could take the call.

“They said they had a role they wanted me to play, and was I interested,” he says. “But they never said what it was. That’s how Marvel is. So I ran through the parts in my head – ‘Let’s see, [Anthony] Mackie’s playing Falcon, Sam Jackson’s Nick Fury...’ And while we’re talking, the limo stopped in front of this antique store – we were trying to get away from these autograph collectors who kept following and knocking on the window. And the window display in this store was all panthers.”

He sits back, still in wonder. “My grandmother would say that God is real, and it does feel that way. There’s things you can’t explain away as coincidence. Certain things are meant for you to do.”

Mr Boseman grew up in a religious home, in Anderson, South Carolina, near the border with Georgia. His mother was a nurse and his father worked in a cotton factory. “We weren’t rich, but I had what I needed.” And his extended family was huge. “When my grandmother died, she left 115 grandkids and great grandkids. That was just one side,” he says.

He had a happy childhood, and was well behaved. But racism was ever-present. “It’s not hard to find in South Carolina. Going to high school, I’d see Confederate flags on trucks. I know what it’s like to be a kid at an ice-cream shop when some little white kid calls you ‘nigger’, but your parents tell you to calm down because they know it could blow up. We even had trucks try to run us off the road.”

He had no interest in acting at first. He studied writing and directing at Howard University. And when he graduated and moved to Brooklyn, that was the career he pursued – writing and directing small off-Broadway plays. It was tough to pay the rent sometimes. He’d be reduced to eating oatmeal and fishing in the change jar for the subway fare. “But I did voiceover work, I taught acting, I got by, one way or the other.”

He stumbled into acting. He was trying to interest a producer in a script of his, and the producer said yes, but only if Mr Boseman auditioned for the lead of play he was putting on. Mr Boseman got the role, found his calling and spent the next few years playing bit parts on TV, some Law & Order, some ER. Then suddenly, a quantum leap: a callback for 42, to play Mr Robinson. And everything changed.

“After 42, I couldn’t even tell you how many scripts about real people have come across my desk – so many,” he says. You became the black American icon guy? “I know, but it’s not intentional. I didn’t think I should do Get On Up at first. Same for Marshall. I had to be convinced.”

With Get On Up, he wasn’t the only one who took convincing. Mr Brown’s extended family had him visit to judge his impersonation in the flesh, though Mr Boseman refused to be put on the spot in the end. His electric performance remains one of the most impressive of its genre, not least because he had only six weeks in which to prepare.

Mr Brown called himself the hardest-working man in show business, and these days, Mr Boseman can relate. “Any time money or fame comes, you should grab it,” he laughs. And that’s what he’s doing. When asked what he does in his downtime, he laughs. “What downtime?” Work is keeping him in Atlanta for much of the year, away from his LA home in Los Feliz, not far from Echo Park. He has written scripts that are in development at various studios as we speak. And every day, rain or shine, he’s in the gym, maintaining his Black Panther physique. “I don’t mind. It’s a great regime,” he says. “Maybe the handsomest years of my life.” He was not, it should be noted, a vegan while getting in superhero shape.

Is it easier handling this rush of success because it has come to him at 41, somewhat later than most? He looks sceptical. “You say later, but when did it come to Denzel [Washington] or Sam Jackson or Morgan Freeman? And why is that? I don’t have the answer, but it’s a question to pose. The industry looks for white actors and actresses, but it’s not the same for black actors. We have to really put the work in.”

As the launch of Black Panther edges closer, questions such as this are coming to the fore. All part of the cultural and political moment that Mr Boseman is a part of. His Twitter feed shows his willingness to engage politically. He’s spoken out in support of Mr Kaepernick, for example. He’s not worried about whether President Trump supporters may be put off his movie as a result.

“If you can’t separate what I believe on a certain issue from the movies I make, why am I worried about you anyway?” he says. “If I don’t agree with Clint Eastwood, doesn’t mean I’m going to stop watching his movies.”

We talk for a while about these fractious times. Does a movie such as Black Panther feel like progress in the midst of it all? Again, Mr Boseman strikes a note of caution. “Let me give you an example,” he says. “When I was shooting Captain America: Civil War in Atlanta, I used to drive back on off-days to go see my family in Anderson. It’s about two hours. And I would see the Klan holding rallies in a Walmart car park. So it’s like we’re going forwards and backwards at the same time. People don’t want to experience change, they just want to wake up and it’s different. But that – shooting Civil War as Black Panther and then driving past the Klan – that’s what change feels like.”

Black Panther is in cinemas 12 February (UK); 16 February (US)