THE JOURNAL

In the late 2000s, fashion photographer Mr Mikael Kennedy started selling 100-year-old Persian rugs out of a classic Mercedes, rolling them out on the bonnet of his car in New York City as if it were performance art. “Everyone I knew thought I was insane,” he says. “They were like, ‘What are you doing? You’re a rug dealer now?’

“I remember sending an email out about it to everyone on my photography mailing list and this person wrote back, ‘How dare you email me about rugs?’ But I thought, you’re just having a bad day. You’re going to be late to the party. This is going somewhere. I don’t know where. But this is very interesting.”

He was right about that. More than a decade later, what started as a hobby rifling through the back rooms of rug stores (“I look for the rugs other people aren’t selling; I find them fascinating”) has morphed into much more than a side hustle. Kennedy’s growing collection of distressed rugs is now housed in a private showroom and design studio in Los Angeles, where he has lived for the past seven years with his wife and daughter, and has since expanded into the burgeoning fashion brand, King Kennedy Rugs.

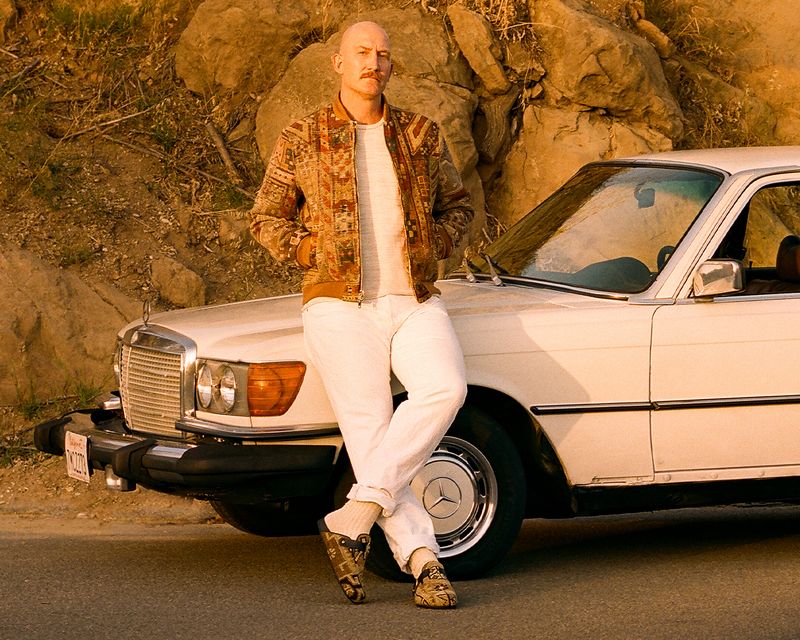

“There’s a tag line for the clothes that I call ‘clothing for the collapse’,” says Kennedy when he greets me at the showroom to talk through the collection of coats (a trench coat, bomber, chore coat and roper coat), camo pants, mules and boots that are featuring in Small World, MR PORTER’s global celebration of craft and communities. “It feels a little science fiction, what the ravers in Blade Runner would wear.”

Hang on, weren’t we just talking about ancient hand-woven textiles? “I didn’t want to make a jacket that actually makes you look like you’re wearing a rug,” says Kennedy, running his fingers along a Caucasian rug pattern from the 1800s that’s been digitally printed on organic duck cotton.

“I’ll pick one of my favourite rugs or patterns and play around with it on the computer,” he says. “Sometimes I blow up the print so it feels a little bitmap, where you can see the actual weavings in the print. The first coat I made bled out like water colours. It’s always an experiment. I embrace what some people might call accidents. That’s what I consider to be the actual magic and point of it."

“The magic is that you can trace each rug back to a specific person or tribe. Every rug is essentially a map of humanity”

Born and raised in Vermont, Kennedy, whose photography clients include Ralph Lauren and J.Crew, is pretty hands on for someone with no formal training in fashion. “I don’t know anything about making clothes,” he says. “I only know how to take pictures of them.”

What Kennedy lacks in technical design skills, he makes up for with his passion for culture and community. “Los Angeles is a factory town,” he says. “You can make anything here. There’s a family in Van Nuys [a neighbourhood in the San Fernando Valley] who are third-generation rug experts and they reweave pieces for me if they’re broken. There’s a very small community nationwide of these old families who have been dealing rugs for a long time.”

Kennedy is also remarkably self-aware. “I’m a giant white dude who is making things out of other cultures’ pieces,” he says. “But because I have a deep love and interest and I’m coming to it from an educated standpoint, the response has been really positive from the community. I don’t think I would do it otherwise.”

Kennedy first encountered this community after a chance meeting with a rug dealer on his travels in Western Massachusetts (“I don’t sit still very well”) kickstarted his collection in 2009. Posting his wares on Instagram, he was quickly inundated, not just by people hoping to purchase the rugs, but by third and fourth-generation Persian dealers who wanted to connect with him.

As a result, Kennedy is critical of the emergence of young dealers jumping on the Instagram bandwagon without awareness of the culture and history of the movement. “I’ve done my best to call them out,” he says. “They’ll rename the rugs Alice or Susie, which is fully whitewashing the cultural history of the rug. To me, the magic is that you can trace each rug back to a specific person or tribe. Every rug is essentially a map of humanity.

“There’s a long history and tradition of artisans making objects out of rugs and what I’m doing is a more modern take on it. But I have a strict moral code and there are certain rugs I will never cut up or use for projects, such as prayer rugs, Afghan war rugs and Navajo rugs.”

“When they sell out, I’ll never reprint a pattern. Once a rug is used for a coat, it’s done. I want everything to feel special”

With photography projects on the horizon (a gallery show of giant landscapes shot from car windows and a book of Polaroids), Kennedy is still committed to his day job. It’s just that, while he once worked out of a dedicated photography studio with a pile of rugs in the corner, he now works out of a rug showroom with boxes of photographs in the corner. Even the Mercedes is upholstered these days. It’s less a salesman’s suitcase, more an emblem of success.

Kennedy is going somewhere, that’s for sure, even if he secretly harks back to the days of rolling out rugs on his car bonnet.

“I met with an investor a while ago who was like, ‘Your company should be this big,’ and he listed some million-dollar number,” says Kennedy, shaking his head. “I was like, ‘It’s 3.00pm and I’m going to go home and play with my kid. I like that better. What if I do 10 per cent?’

“There is no dream of turning this into a massive thing. I don’t want to spend my life working. When we made the printed coats, there were 50 or less of every piece because nobody wants to walk down the street and see five other people wearing it. When they sell out, I’ll never reprint a pattern. Once a rug is used for a coat, it’s done. I want everything to feel special and magical.”

Long may King Kennedy reign.