THE JOURNAL

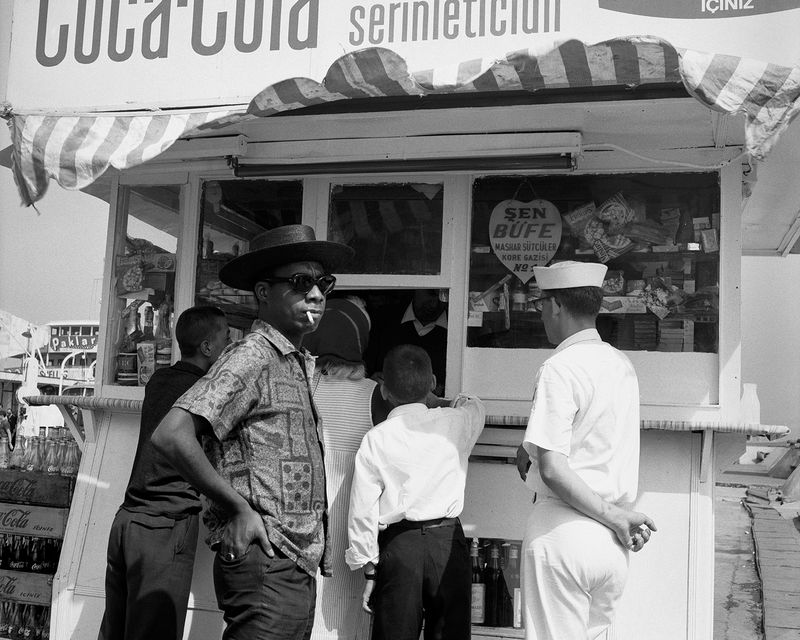

Mr James Baldwin in Istanbul, 1965. Photograph © Sedat Pakay

Ms Nina Simone, Mr Richard Pryor and Nipsey Hussle all sat on my couch, staring at me. Well, not them, but their faces rendered in living colour on three black T-shirts. Nina wore pearl earrings, a short Afro; her eyes saying, “Pick me or don’t, I don’t care.” Richard sported a larger Afro, his gaze cast upward, as if in conversation with God. And then there was Nipsey the Great, snapback turned around, mouth half-opened, ready to dispense a gem or two. This was February 2021. I’d become a published author and New York Times bestseller the month prior, but in that moment, I was just a guy trying to select a T-shirt to wear for a virtual event. The kicker here being that whichever shirt I selected was going to be worn under a sweater, so no one, except myself, would even know what it was.

A hilarious quandary? Maybe. But I can’t help but think that Mr James Baldwin would understand. Because aside from being one of the most influential authors of the 20th century, he was also a fierce sartorialist whose fashion choices continue to impact writers today.

You know, I can’t recall the first time I saw a photo of Baldwin. Perhaps it was in high school or college, before or after reading Another Country and Going To Meet The Man – a novel and a short-story collection that enraged me to the point that, for at least a week after reading each, I felt a heart-deep hatred for the world we live in. It wouldn’t be the last time his work had this effect on me. But beyond the revolution in his prose, what equally stood out to me was the defiance in his clothes.

Turn out the lights and cue the slide projector.

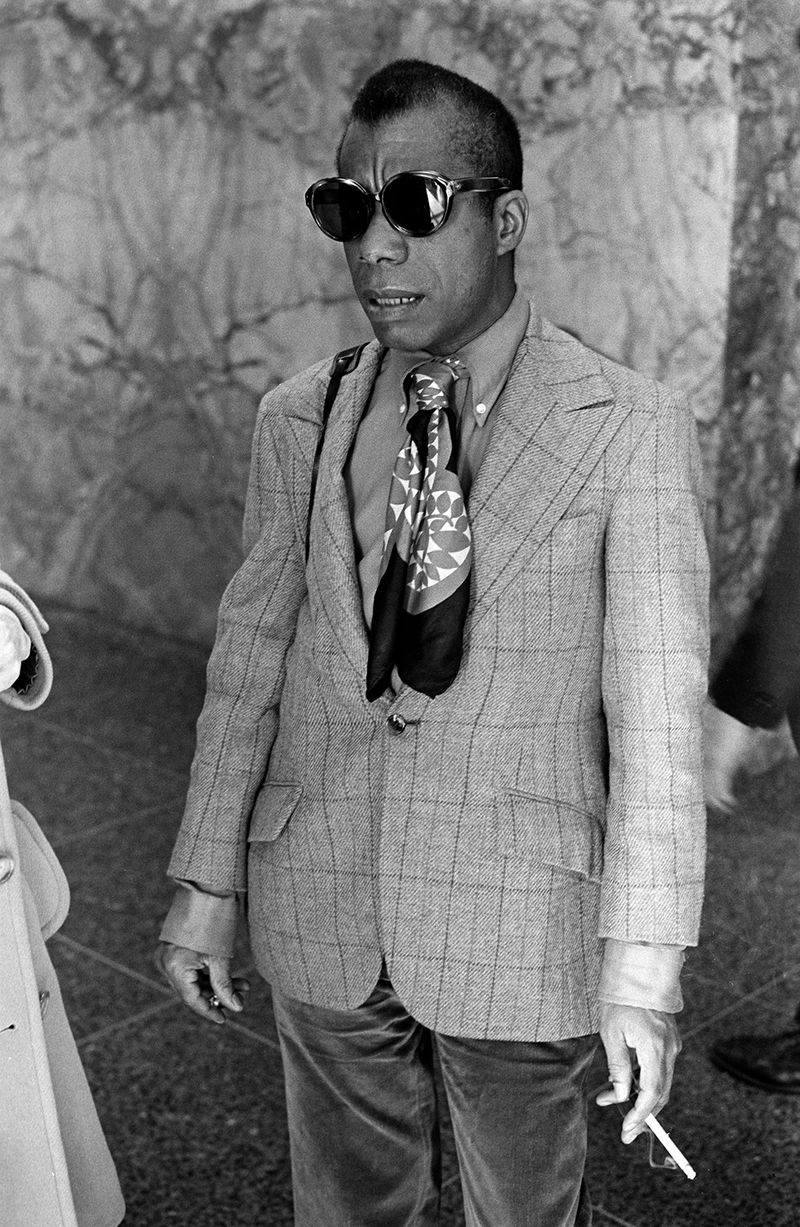

Mr James Baldwin in San Francisco, 1969. Photograph by Mr Stephen Shames/Polaris

Exhibit A, above: black sunglasses, resembling tinted windows, cover a third of Baldwin’s face. He wears a scarf as a tie over a long-sleeve button-up and his trousers are made of a velvet so smooth you’d think he’d dipped his legs in angel food. Here, I don’t see an author, but a full-fledged rock star; someone whose power was so potent they wouldn’t dare hide it.

Click.

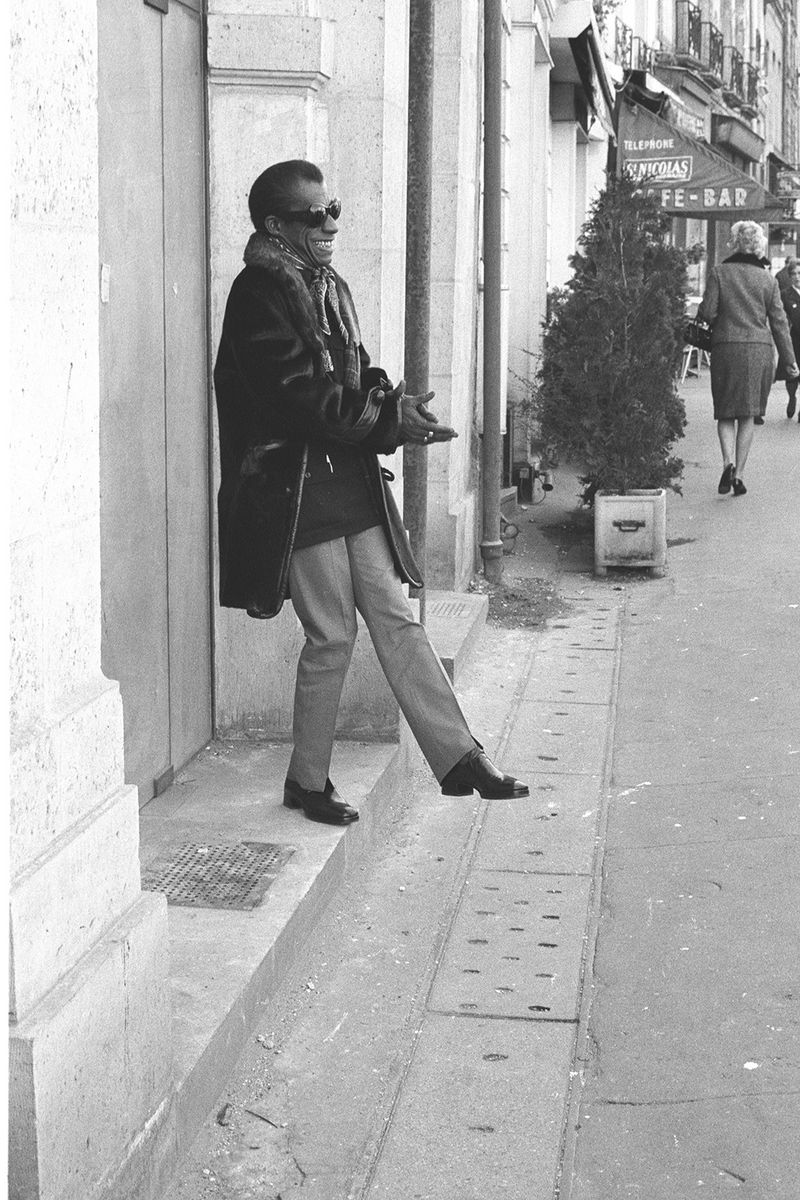

Exhibit B, below: Uncle Jimmy in Paris. Our man is decked out in a thick black jacket with fur trim, another scarf tie, a shirt jacket, slacks with pleats sharp enough to cut a steak, and leather shoes that were probably mooing. He is smiling, clapping; one foot in mid-air as he steps off a ledge. Freedom in the flesh.

Click.

Exhibit C: see Baldwin’s appearance on a 1968 episode of The Dick Cavett Show, where he sits with legs and hands crossed on a couch, looking like Mr GQ – dark suit, white shirt, dark tie. He’s about to decimate a respected professor who believes he knows what Black Americans need in order to progress. Murderous poise never looked so suave.

Mr James Baldwin in Paris, 1972. Photograph by Ms Sophie Bassouls/Sygma via Getty Images

These are just snapshots of a man whose creative, social and political sentiments were stitched into the fibre of both his being and the threads that adorned him. He seemed just as at home in a scarf he’d turned into a tie and bug-eyed black sunglasses as he did in a Don Draper-esque suit. His choice of clothing said, “I can dress like you if I so choose, but I am not you, nor will I ever be. And you’re still going to get these proverbial hands.” And everything he wore – whether a plain white T-shirt or a hat that brought to mind some Italian peasant or Soviet leader – made a statement, the loudest being: “either due to the refinement of my garments or the brilliance of my words, you will not ignore me.”

“[Baldwin’s] creative, social and political sentiments were stitched into the fibre of both his being and the threads that adorned him”

Baldwin’s level of at-homeness in any situation or ensemble was extraordinary, and I believe it stemmed from two places: the first being his unshakeable knowledge that while he could clothe himself in ways that would be stunning to some and crude to others, what mattered most was the fineness of his spiritual core. The second being trauma. Trauma from feeling out of place as a queer man in an anti-queer church, in Harlem when he was likely one of the few, if not the only one, reading Dostoyevsky in fifth grade, and in a country that had never, as he once said, pledged allegiance to him or any other Black people. It may seem strange to mention trauma in the context of a man who exuded great magnitudes of confidence, but oftentimes it is the former that births the latter.

Mr Mateo Askaripour in Brooklyn, New York, 2018. Photograph by Mr Andrew Askaripour/FifthGod

I understand this instinct to adapt and reinvent; to feel as though if you do not change, then you will suffer a zombie-like existence where you’re walking and talking like a person, but are in reality only playing a part that was written by the world’s socially-constructed standards. So, we buck against it – heating, hammering and beating ourselves in an attempt to forge an identity that feels real, despite, at times, not being entirely sure if what we see in the mirror is fool’s gold or bona fide 24K. Still, clothing, just as any other art form, serves as another outlet of expression for who and how we want to be, an emblem of irreverent liberation, containing equal amounts of beauty and utility.

Like Baldwin, my aesthetic is empowerment, and the outfits I wear need to meet the moods I choose to embody. A made-to-measure suit reminds me I’m not messing around. A laid-back combination of some neutral-coloured T-shirt, pants and maybe a waistcoat, with Vans on my feet, for when I want to tone down whatever over-the-top energy I plan to give off. Hence the T-shirt dilemma I began with – whichever one I went with was going to endow me, and the words that came out of my mouth, with a certain aura.

“Both in writing and fashion, you should break the rules; that demands, of course, knowing what they are”

Fortunately, I am not alone in this thinking. Author, activist and Netflix exec Mr Darnell Moore says that clothing symbolises “Freedom. Freedom of expression. Freedom of self-determination and self-actualisation. Freedom as a breaking away from the ‘rules’ especially that of gender.” Mr Robert Jones Jr, New York Times bestseller and National Book Award finalist, asserts that his choice of attire is “a call back to my ancestors and elders”, and that his favourite fit is “like I’m rocking 2022 and 1932 at the same time, which is to say the outfit is timeless”.

Left: Mr Darnell Moore inWest Hollywood, California, 2022. Photograph by Mr Sean Howard. Right: Mr Robert Jones Jr in Bedford Stuyvesant, New York, 2020. Photograph by Mr Al Vargas for Rain River Images

In the same way you can look at a photo of Baldwin and feel that his literary and sartorial sense of style are intertwined, Pulitzer Prize-winning author Mr Mitchell S Jackson aims to have his “personal style and literary style be memorable”, which means “creating contrasts; tux pants with a T-shirt, or slacks with a wool work shirt.” He also tries to do the same with language: “Combine what could be considered high and low diction. I also think that both in writing and fashion, you should break the rules; that demands, of course, knowing what they are.”

For New York Times bestseller, two-time National Book Award finalist and National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature Mr Jason Reynolds, his aesthetic “is centred around unvarnished, black garments instead of focusing on compelling colours and embellishment”. This minimalist approach is rooted in imposed restriction, because when he began making money, he realised “my love of clothes might leave me broke. I needed to find a way to limit myself, and the best way to do so was to limit the palette.” Golden Goose sneakers, John Elliott T-shirts and a vintage gold Rolex GMT are a few of the pieces that comprise his understated, but undoubtedly quality, look.

Left: Mr Mitchell S Jacksonin his Harlem apartment, New York, 2019.Photograph by Mr John Ricard. Right: Mr Jason Reynolds in Washington DC,2020. Photograph by Mr Adedayo Kosoko

There’s also the question of, “Should the clothing we authors wear even matter?” But I’ll save that for another article. What’s more interesting to me now is how your look can affect the way you and your work are perceived. I asked each of these authors if they believe there’s a connection between the way they dress and how the public receives them, and while Reynolds says, “I’m not sure, because what the public thinks of me ain’t none of my business”. Moore, Jones Jr and Jackson heartily agree: hell yeah, it does.

It’s clear that these men, not only because of their literary excellence, but also the freedom they represent with their individual styles, are Baldwin’s progeny. You feel this when you see a photo of Moore shining in the Californian sun; Jackson posing on a sidewalk like a Paris Fashion Week catwalk; Reynolds spitting poetry in black-on-black-on-black-on-Black; Jones Jr putting all to shame with a brazen bow tie. They are making it clear that they will never dim their light to conform to the limited visions of others, inspiring us to simply be ourselves – a difficult pursuit, yes, but also one of the most courageous and original we can ever attempt.